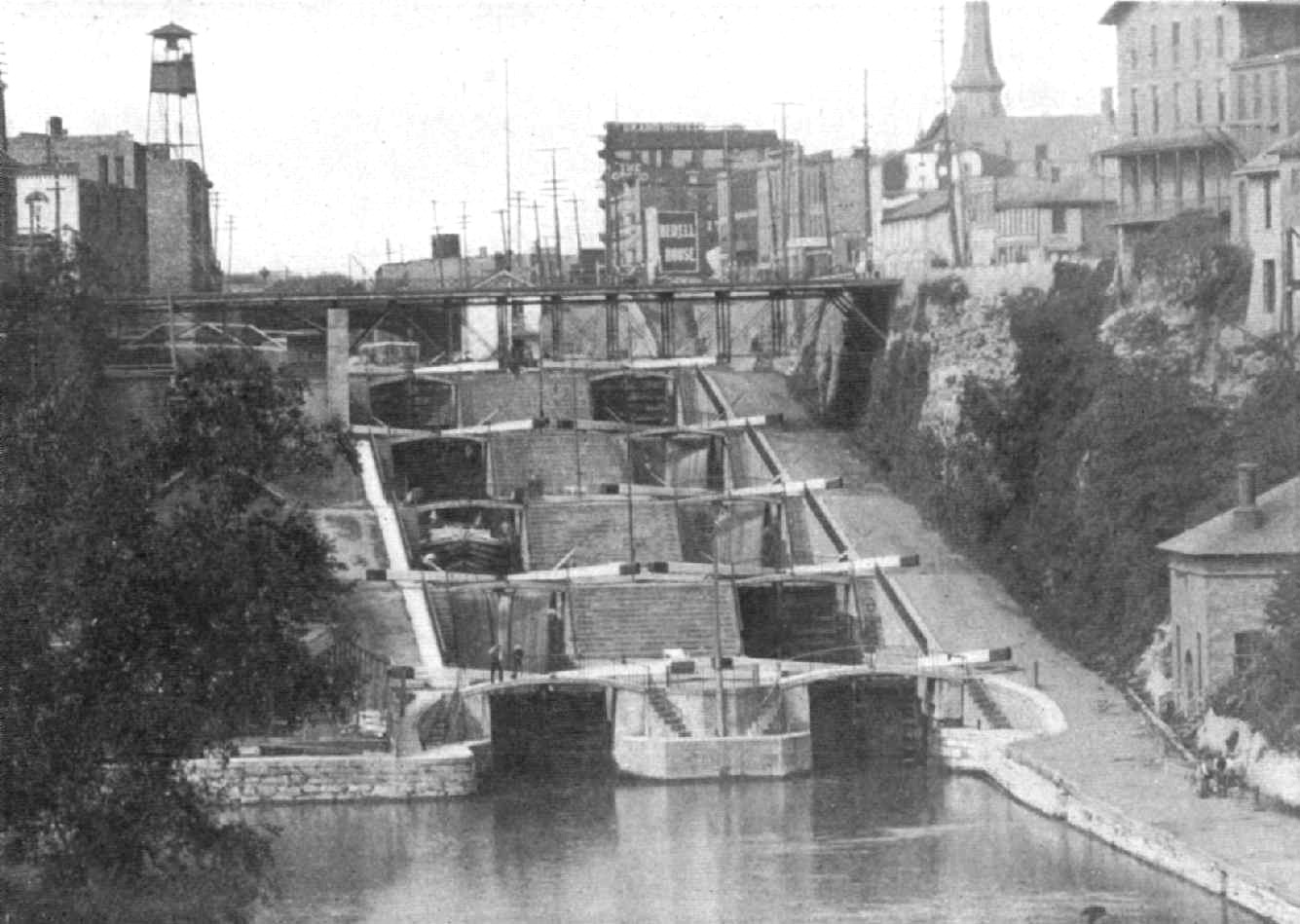

THE COMBINED LOCKS AT LOCKPORT. (Copyright by O. N. Ranney.)

HISTORY OF THE CANAL SYSTEM

OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK

TOGETHER WITH BRIEF HISTORIES OF THE CANALS

OF THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA

VOLUME I

BY NOBLE E. WHITFORD

From the legislative enactment authorizing a nine-foot channel to the beginning of the third enlargement, or the Barge canal.

The division of the history at this point is somewhat arbitrary, for, as we have seen, the agitation which culminated in the second attempt to enlarge the waterway started several years earlier, but the beginning of 1895 marks the time when the project was definitely formulated in law, just subsequent to the popular declaration for some radical form of improvement.

The constitutional amendment to section 10, article 7, became operative on January 1, 1895, and this year promised to be one of increased activity in canal matters. A complete transfer of political authority in both executive and legislative branches of the State Government had occurred, and it was hoped that great benefit would inure to the whole commonwealth from the new order of things.

The National Government had deepened the lake channel from Chicago to Buffalo to twenty feet, and the Hudson river to twelve feet, while the Erie canal remained at seven feet for boats drawing only six feet. The Canadian Government was also preparing to enlarge its system from twelve feet to twenty feet, from Chicago to Montreal. These facts mainly led to a convention of mercantile exchanges which was held in September of 1894 at Toronto, Canada, in which delegates from the western cities in the grain belt participated. The Georgian Bay canal project was inaugurated, shortening the haul to tide-water several hundred miles, and promising to be a dangerous competitor to the canal systems of our own state.

The Governor urged upon the attention of the Legislature the necessity of prompt action upon the question of improving the canals, and the State Engineer, in his annual report for 1894, presented an elaborate argument as to the value of the canals to the State and the necessity of their permanent improvement. All the improvements so far were of a temporary character. Comparisons were presented between the efficiency of the canal as it then stood, on the one hand, and the five great competing trunk lines of railway, as well as the Canadian canals, on the other. The idea of a ship canal the State Engineer deemed to be impracticable, and he recommended that the canals be improved by (1) deepening to nine feet, (2) lengthening the remaining locks, (3) the use of high lifts where necessary, (4) greater speed by the use of electric towage and (5) reducing cost of maintenance.

As to electric propulsion, he reported that the Milligan system appeared to supply all the necessary requirements and to solve the problem of easy and rapid canal transit. This system, briefly stated, consisted of a line of fourteen-foot posts in the rear of the tow-path, bearing two continuous rails, known as the east and west-bound rails, about three feet apart. A twenty-horse-power motor ran on these rails and from the motor a tow-line connected with the boat. 1

Immediately upon the assembling of the Legislature of 1895 the subject of canal improvements was considered. On January 9, in the Assembly, Mr. Clarkson introduced a bill making provision for issuing bonds to an amount not to exceed nine millions of dollars for the improvement of the Erie, the Champlain and the Oswego canals, and providing for the submission of the measure to be voted upon by the people at the general election of the year 1895. 2

After the usual procedure this bill was finally passed by the Assembly on January 19, by a vote of eighty-three to thirty-one and by the Senate on February 21, by a vote of nineteen to four. It became a law on March 9, 1895, with the Governors approval, and in accordance with its terms and with constitutional requirements was submitted to the people at the ensuing November election for approval. In the event of such approval it was provided in the bill that the Comptroller should issue not more than nine million dollars in semi-annual four per cent bonds, to run not more than seventeen years and to be sold for not less than par, in lots of not more than four million dollars at one time. Premiums were to be applied to the sinking fund established for the payment of principal and interest, and an annual tax of thirteen-hundredths of a mill upon all taxable property was authorized for this fund.

By the terms of the bill (ß 3) as applied to the Erie canal, the improvement was to consist of deepening the canal to a depth of not less than nine feet of water, except over aqueducts, miter-sills and other permanent structures which might be left at eight feet. The deepening might be accomplished by raising the banks where practicable. Locks remaining to be lengthened were to be improved and provided with necessary machinery, and vertical stone walls were to be constructed where required.

The usual number of appropriations for special canal purposes was also made by the Legislature of 1895. The amount of these special appropriations was afterwards stated to be about $660,000. 3 Among them were $77,500 from the balance remaining of the fund for deepening the canal under chapter 572, Laws of 1894, reappropriated to lengthen locks Nos. 21 and 22, and $10,000 from the same source to dredge lower Black Rock harbor (chapter 320); $31,250 to build the Stateís half of a bridge at Porter avenue, Buffalo, the city to contribute an equal amount (chapter 18); $25,000 for a bridge at Exchange street, Rochester (chapter 514); $18,000 for bridge changes in motor power at Genesee street, Utica (chapter 170); $30,000 for drainage of State ditches at Cowassalon creek and swamp (chapter 366); $20,000 for drainage at Tonawanda (chapter 19); $10,000 for a similar purpose (chapter 307) and $20,000 for the repair of the dam at Rexford Flats (chapter 560).

Senate resolutions were also introduced reciting the facts that the canals annually cost one and one-half million dollars to maintain; that many other states were benefited by their service as a through freight rate regulator; that it was the policy of the United States to maintain interstate waterways; that the people could not sell the canals constitutionally; and that it was inequitable that New York should bear the entire burden of their maintenance while other states enjoyed their principal benefits. The resolutions instructed their Representatives in Congress to support and urge the passage of a bill providing that the United States Treasurer should annually pay to the Comptroller of New York three-fourths of the expense of their maintenance for the preceding year. By this means the opponents of the canals sought to divert public thought from the question at issue and to obtain the defeat of the referendum, but the resolutions were finally tabled. 4

An act providing for the construction of a dam on the Genesee river, for the purpose of supplying water to the Erie canal and of restoring to the owners of water-power on the Genesee river the water diverted by the State for canal purposes, was also passed by both Houses and sent to the Governor, but it failed to secure his approval and did not become a law. 5

In November, 1895, under Senate resolution 130, which became a law on March 2, 1895, the President appointed a United States Deep Waterways Commission, consisting of James Angell, John E. Russell and Lyman E. Cooley. The report made to the commission by Mr. Cooley contains a large amount of valuable information on this subject and is accompanied by profiles of all the routes, giving information not before published. The report of the commission was published under date of 1897, as H.R. Doc. 192, 54th Congress, 2d Session.

The publication which contained the most general discussion upon the subject of New York State canals was that of the proceedings of the International Deep Waterways Association, which met at Cleveland, Ohio, on September 24-26, 1895. The proceedings of this convention were published in a book of four hundred and sixty pages which contains a vast amount of valuable discussion on the general subject, including articles by Thomas C. Clarke, Lyman E. Cooley, Chauncey N. Dutton, S. A. Thompson of Duluth and others. 6

Navigation opened on the canals on May 3 and closed December 5, for the season of 1895. Lake navigation was open after April 4, and the Hudson river from April 2 to December 9. The season was remarkable as being the dryest in many years. Lakes Erie and Ontario were from two to four feet below their normal elevation. Extreme care was used in drawing upon reserve supplies, but an abundant supply for navigation in the canals was maintained. At Buffalo, on several occasions, with adverse eastern winds, the canal surface was lowered four or five feet and the unusual sight was presented of loaded boats lying hard and fast on the bottom of the canal until the wind shifted and the prism was again filled to its usual level. 7

An innovation in canal boat construction should be noted for August of 1895, in the trial trip of a fleet of steel canal boats -- one steamer and five consorts -- put in commission by the Cleveland Steel Canal Boat Company. A thorough working trial was given them, with very satisfactory results and three more fleets on improved plans were ordered. The boats were about ninety-eight feet in length, by eighteen feet beam, and ten feet deep, made of three-eighths-inch open hearth steel. Light, they drew one and one-half feet; capacity of consorts on a six-foot draught, two hundred and thirty-five net tons, and of propeller, one hundred and thirty net tons. The latter was fitted with fore-and-aft compound engine of one hundred and twenty horse-power, and boiler of Scotch type. Diameter of propeller, sixty-four inches, making one hundred and sixty revolutions per minute; approximate cost of propeller, fifteen thousand dollars and of consort, six thousand dollars; time, New York to Cleveland, loaded to six feet, thirteen days. 8

In October of 1895, there occurred another series of tests of electrical propulsion, the trial being made at Tonawanda by the Erie Canal Traction Company, of the "Lamb" system, which consisted of a line of poles along the bank supporting a stationery cableway, on which electric motor carriages traveled, towing the attached boats. The department was represented by Electrician Barnes of Rochester, and his report was made to the Superintendent of Public Works on December 11, 1895. From his computations the cost of propulsion, under experimental conditions that were somewhat disadvantageous, would be, for a boat whose gross weight was two hundred seventeen and one-half tons at a speed of two and one-half miles per hour, 2.1 cents per boat-mile for power or $7.66 per trip and a like sum for tow-motor rental. The energy consumed would vary approximately as the cube of the speed divided by the ratio of speed, and the item for motor rental would vary as the power divided by that ratio. Thus, if the speed should be increased to three and one-half miles per hour, the power would be increased from 8.5 to 23.4 electric horse-power, the cost of current to 4.1, and of motor rental to 4.1 cents, making 8.2 cents per mile, or $29.93 per trip. Making allowance of one-third time for delays there would be twenty-three trips per season at the lower speed and thirty-two trips at the higher speed. This was considered to fall far short of the cost of towage prevailing at the time. In comparison with the trolley system, tried in 1893, several points of advantage were noted. Among them, the elimination of the necessity for building propeller boats, no space required for electrical machinery, and the absence of propeller wash. The system was fully endorsed by the expert. 9

In the Milligan system the motor was carried on rigid rails. There was no sagging between poles, and an even strain on the towing-cable was maintained. It had double tracks upon which two motors traveling in opposite directions might pass without exchanging motors as in the Lamb system. On this last-named system the motor was carried on flexible cables and was much cheaper in both installation and maintenance.

The great interest in enlarged canals manifested by the Deep Waterways Association, and by the results of the recent elections led to a preliminary survey and estimates for an enlarged canal by the "Oswego Route" by Resident Engineer Albert J. Himes, [see errata] under direction of the State Engineer, in the fall of 1895. The route was from Troy through the Mohawk river to Rome, thence into Wood creek and across Oneida lake, thence down the Oswego river to Lake Ontario. This was, to a certain extent, the line suggested by Elnathan Sweet in his paper before the American Society of Civil Engineers in 1884. The Mohawk river was to be canalized into a series of level pools by means of dams. The bottom width was to be one hundred feet, the depth of water twenty feet, and the locks four hundred and fifty feet long by sixty feet wide. Huge elevator lifts were to be used, one at Cohoes of one hundred and thirty feet and another at Oswego of half that height. The length of the contemplated canal was one hundred eighty-two and one-half miles and the total cost of the enlargement was estimated at eighty-two million dollars. 10

Only twenty-seven boats were registered during the year 1895, of which seventeen were from two hundred and forty to two hundred and fifty tons. The total tonnage of the canals for the year was 3,500,314, compared with 1894, a loss of 1,000,692 tons, of which the loss in wheat was 622,996 tons and in corn, 177,453 tons. The total receipts of flour and grain delivered at the port of New York by all routes during the season of canal navigation was equivalent to 87,783,418 bushels, of which the canals brought 14,612,700 bushels or 17.08 per cent. These figures show a large falling off in the trade and tonnage of the canals for 1895.

This was another year of great commercial stagnation, although conditions were somewhat better than during the previous year. It had probably proved to be the most disastrous to canal interests of any within the past sixty years, by reason of the ruinous competition of the parallel railway lines and the comparative inefficiency of the canals. Without any apparent reason the railroads reduced their rates nearly fifty per cent below those of the year before, and to a point which was profitable neither to themselves nor to the boatmen. The Legislature had decided to refer the question of expending nine million dollars in canal improvements to the people at the November election. If the canals and their usefulness could be discredited by an overwhelming reduction in tonnage before the election, might not the vote upon the amendment be negatived and the canals remain in desuetude as a competitor? This explanation was officially suggested. 11

Certain obnoxious exactions by lock-tenders from the boatmen had gradually attained such proportions as to call for vigorous action by the Superintendent. Particularly was this the case at Lockport and at the "sixteens" near Cohoes. Boatmen had to pay tribute in passing these locks or suffer personal abuse, delays, swelling of boats against the walls, or flooding of their boats. It was little better than highway robbery and had been too often winked at by officials. During this season a vigorous effort at length effectually stamped out the system.

The condition of the bridge over the canal at West Main street, Rochester, demanded attention and, by chapter 625 of the laws of 1894, the State Engineer was required to prepare plans for a complete overhauling of the structure, or if the cost of these repairs should approach that of a new bridge, then to submit estimates for the latter to the Legislature. In September of 1894, Mr. George W. Rafter was instructed to visit and inspect movable bridges in Europe, with a view to the selection of some appropriate type adaptable to this and other points on the canal. Meantime certain repairs were made to the existing bridge, which bettered conditions materially.

Mr. Rafter submitted an interesting report to the State Engineer on January 15, 1895, reviewing the various forms of movable bridges in different countries, but he seemed to find no type among them particularly adapted to use upon the Erie canal, either for general service or at the Rochester crossing. He was impressed with the advantages of fixed bridges of high span with long easy approaches, both in point of beauty and utility, and recommended their use for canal crossings wherever practicable. 12

In view of Mr. Rafterís report, new plans were, therefore, prepared in 1895 for a lift-bridge, with pressure applied to cylinders by an accumulated weight operated by a water-wheel driven by water from the canal. But owing to the fact that local public opinion was divided as to whether a fixed or movable bridge was wanted, and to the unsettled questions arising from contemplated general improvements in the canal under the "Nine Million" act, the State Engineer, in January of 1896, recommended to the Legislature that no immediate action be taken. 13

Various devices for the propulsion of boats were at this time given careful consideration. The State Engineer recommended an electrical propelling device, invented by C. N. Dutton, as being superior to any yet tested, in the low cost of construction, the ease with which boats could pass without switches or double tracks, and the facility with which wide waters could be crossed. The economy in construction would insure to every boat a motor and screw, while only every fourth boat would need to be so supplied. In general terms, it consisted of a cable of twisted wires supported on posts; an adjustable propelling apparatus carried on the boat and a trolley pole, controlled by the steersman, and of a length sufficient to reach the conducting cable from any portion of the navigable canal. Bulgerís adjustable propelling apparatus with feathering paddles intended to eliminate bank wash was similarly brought to notice. 14

At the November election, in 1895, the people again expressed their determination that the canals should be improved and the law providing for their enlargement was ratified by a majority of 276,886. As soon as the State board of canvassers had declared the results of the ratification of the "Nine Million" law, which they did on December 12, the Comptroller advertised for sale bonds to the amount of two million dollars. Unfortunately, at this juncture, Venezuelan complications with Great Britain arose, and another Government bond sale was ordered, but notwithstanding these difficulties, $1,770,000 was sold on January 9, 1896, at a premium of 1.378. These were three per cent, ten-year bonds, due in 1906.

As to the manner in which the general improvements authorized by the "Nine Million" act should be executed, the Superintendent of Public Works held the opinion that any substantial improvement short of a deep waterway, or ship canal, should have as a central idea the increase in speed of boats of existing tonnage, rather than the increased section of waterway, and in his view the appropriation available was for the necessary rebuilding of dilapidated structures, the restoring of strength and durability to the canal and for putting it in perfect condition rather than for its enlargement, except as to depth. The purpose should be to increase the number of boat trips appreciably, in anticipation of the adoption of improved methods of propulsion by steam or electricity. 15

By January 13, 1896, surveys were started over the entire length of these three canals, a distance of four hundred and fifty-four miles. Twenty-eight survey sections were allotted to as many parties and over two hundred men were drawn from the civil service lists and put into the field, in order to obtain the necessary data for plans before navigation opened. This done, the forces were reduced and plans begun. For many years this method of improvement, commonly known as the "Seymour plan," had been the subject of general discussion. In the preparation of plans many unforeseen difficulties were presented. 16

To deepen the Lockport level of twenty-eight miles, much of it through rock, was a puzzling proposition. Assistant Engineer George W. Rafter was, therefore, assigned to make a thorough investigation of the question of water-supply from Lake Erie and other sources on the western division. On April 1, Mr. Rafter submitted his report, which appeared in Appendix I of the State Engineersí report for 1896. Thereafter during the year plans were made covering the improvements at Lockport.

The question of raising the banks or deepening the bottom, especially through cities, was often determined by the grade of important bridges or other structures or by extensive commercial establishments on the canal banks, again by the feeders and the heights of their dams, and in other cases by the level of important aqueducts or other controlling features. All of these difficult matters largely account for the seeming delay in beginning construction. 17

The river and harbor act, under date of June 3, directed the Secretary of War to cause to be made accurate examinations and estimates of the cost of a ship canal for the most practicable route, wholly within the United States, from the Great Lakes to the navigable waters of the Hudson river, of sufficient capacity to transport the tonnage of the lakes to the sea. The Secretary of War detailed Major T. W. Symons, Corps of Engineers, U.S.A., to prepare this report. It contains a discussion of the general proposition of the various routes and of the class of vessels adapted for their navigation. In its conclusions this report states that the route considered best for a ship canal is by the Niagara river, Lake Ontario, Oswego river, Oneida lake, and the Mohawk and Hudson rivers; also that the Erie canal, improved and enlarged and modified to give a continuously descending canal from Lake Erie to the Hudson, and the canalizing of the Mohawk river will give better results than a ship canal and at one-quarter the cost.

On April 1, 1898, this report was discussed at length before the House committee on rivers and harbors of the Fifty-fifth Congress by Mr. S. A. Thompson, of Duluth, who was later Secretary of the board of trade of Wheeling, West Virginia. This discussion contained a great amount of valuable information and was published by the Government printing office in 1900, under the title of "Proposed Ship Canal Connecting the Great Lakes and the Atlantic Ocean." 18

In 1896 the United States Deep Waterways Commission published a report with map and sectional profile showing the most direct line through the Oswego-Oneida-Mohawk valleys, between Oswego and Troy, following the channels of the rivers and the lake and showing their materials. These were made by Wm. Pierson Judson and are described in the report by the United States Deep Waterways Commission to be "the first map and profile adequate for the consideration for a ship canal." These were also published separately with title "Lake Ontario to the Hudson River, 1896." 19

In the way of canal legislation for 1896 a radical difference in methods of appropriation was manifest. By the terms of chapter 947 a general tax of one-tenth of a mill was imposed, which was expected to yield revenue of about $425,000. Of this amount, in compliance with departmental suggestions, $50,000 was devoted to the installation of a general system of electric communications on the canals, and of the remainder $125,000 was available to each division for use in extraordinary repairs and improvements on that division. At the close of the year it was stated that the wisdom of this course had been fully vindicated and a similar appropriation of $360,000 was asked for the ensuing year. 20 The customary special appropriations for various canal purposes were almost entirely lacking in this yearís legislation. Very few of these were passed, and only for small amounts.

Chapter 881 of the laws of 1896 permitted floating elevators to be maintained on the canals at stations to be assigned by the Superintendent; chapter 794 amended chapter 79 of the previous year, as urged by the Superintendent, shortening the time of advertising contracts and so facilitating the work; while in the "Supply Bill" was an item appropriating ten thousand dollars for making further investigations as to the foundations of the proposed dam at Mount Morris and as to the best means of transporting materials to its site, and also for making detailed plans.

Navigation opened on the canal on May 1 and closed December 1, two hundred and fifteen days; the Hudson river was open from April 7 to December 19 and Lake Erie opened to navigation at Buffalo after April 19. Less trouble was experienced at the latter place, from low water in the canal, than in any previous year. It was hoped that the work to be done under the general improvement act would entirely relieve this trouble.

As promised, two or three more fleets of steel boats were added to the service during the season and were remarkably successful in their results. The trip from Cleveland to New York was made in from ten to twelve days, and the ability of the boats to withstand heavy gales while on the lake was encouraging. In the estimation of the projectors it was believed that they could successfully compete with railways as they then existed, at a fair margin of profit. 21

For the fiscal year ending September 30, 1896, the expense of ordinary repairs and maintenance was stated to be $1,006,453.70. The whole number of tons carried in 1896 by all canals was 3,714,894; of this there were east-bound, 2,605,012 tons; and of through freight, 2,132,956 tons; the Erie canal carried 2,742,438, an increase over 1895 of 214,580 tons. On agricultural products, however, there was an actual increase of 492,656 tons, the small total increase being due to losses in other products. As to comparative flour and grain receipts at the port of New York during the season of canal navigation, May 1 to December 1, the total receipts by all routes were equivalent to 112,121,954 bushels, of which the canals carried 31,672,499 bushels or twenty-eight and one-quarter per cent.

Under the fifty thousand-dollar appropriation to establish a system of electric communications, plans for two different methods of installation were obtained and submitted to an expert for examination and both were approved. The estimated cost was $150,000. Actual construction was deferred until the following season and a second appropriation of $50,000 was advocated in order to secure early completion and benefits from the system.

During the year plans under the general improvement act, to the amount of three and one-half million dollars, were prepared and contracts were let. Generally the work was to begin with the close of navigation.

At the close of the year the Superintendent stated that he had been assured by the State Engineer that the appropriation of nine millions of dollars would be sufficient to secure the depth contemplated in all three of the canals indicated, and added that the contract prices so far made would seem to warrant this prediction. 22 But the State Engineer in his report stated that this sum would not suffice to put the canals in their highest state of efficiency. 23 It was admitted to have been a year of unprecedented financial stress in which the resources of the banks had fallen off thirty million dollars, but Governor Black in his message of 1897 urged the energetic pushing of canal improvements, in order that the full value of the appropriation might be utilized, instead of being frittered away in commissions, boards and other expenses.

Locks Nos. 21 and 22 were placed under construction. These, with possibly lock No. 2, and the three at Newark, were believed to be all that would admit of lengthening in the usual manner. Lock No. 1, at Albany, was regarded as difficult and expensive to improve, and the fact that eighty-five per cent of canal traffic sought the river at West Troy rendered its improvement of doubtful expediency. In place of locks Nos. 3 to 18, known as the "sixteens" it was proposed to build a steel aqueduct from the head of lock No. 18 to a rocky point on the opposite bank of the river, and there to place a mechanical lift of one hundred and forty feet, capable of passing two boats at once. From here the river was to be canalized on the south side to the Champlain canal. The estimated cost of "improving" the existing sixteen locks and levels was $1,686,881. The mechanical lift-lock would cost about two-thirds of this sum. Among the many benefits to be gained by the proposed construction there may be mentioned the saving of thirty-four thousand dollars annually in lock-tending, and the abundant supply of water for the Cohoes mills. The four Little Falls locks would probably be lengthened in the usual manner. At Newark, the three locks were to be reduced to two of higher lift. At Lockport the difficulties were regarded as enormous, but finally plans for a mechanical lift, combined with a new alignment, were decided upon. These lift-locks were to be operated by compressed air, and the preparation of plans was conducted under the supervision of the inventor, Chauncey N. Dutton. 24

It was considered that under the blanket appropriation for each division, provided by chapter 947, the work on extraordinary repairs and improvements was greatly facilitated. The waters from serious leakages were collected and carried away in ditches; numerous deposits of silt under aqueducts and culverts were removed, adding to their safety and avoiding damage suits. Earthen or timber reservoir dams, especially on the middle division, were out of repair, and a great variety of work was done in connection with them, and still more was needed. They were considered to be in much better condition than for thirty years past, according to Division Engineer Gereís report. Several aqueducts required rebuilding and, as they were not expected to be rebuilt under the "Nine Million" act, they were paid for out of the blanket appropriations, and for reasons of economy in view of the forthcoming improvements, were made to carry nine instead of eight feet of water, as directed under the former act. 25

A popular misapprehension seemed to exist as to the scope of the "Nine Million" act, which the Superintendent in his report for 1896 hastened to correct. The general idea seemed to be that it was applicable to the reconstruction or improvement of any structure on any canal. But it was officially construed by the Department to mean that it could only be used on the Erie, Oswego or Champlain canals, and that no expenditures for construction should be made unless such improvement or construction was necessary to, and formed part of the general plan of improvement. It followed that improvements to locks, aqueducts, waste-weirs and culverts, and for cleaning out feeders, creeks, and like expenditures must be made under some other appropriation. 26

The improvements then under way and contemplated would result, it was believed, in a reduction of the tractive power required to move a given weight at a given speed. This would result either in shortening the time of a trip without increasing the motive power or in an increase of load and speed without an increase of power. Experiments so far seemed to warrant the expectation of lowering the cost of movement substantially, even though hampered by a restricted prism, owing to deposits of silt.

On February 22, 1897, the Superintendent of Public Works addressed a communication to the legislature upon the subject of the rate of wages paid by contractors on State work to unskilled laborers. Conditions then prevalent enabled the average working man to earn but twelve and one-half cents per hour, making one dollar for an eight-hour day, or six dollars per week, a sum insufficient for the support of himself and his family. It was suggested that the Legislature fix a minimum price of not less than fifteen cents per hour for unskilled labor on the canals and other State work. A bill was later introduced and passed by the Legislature to remedy this evil, but by clerical neglect it failed to come properly before the Governor and so did not become a law. 27

Under the provisions of the appropriation of ten thousand dollars (chapter 950, Laws of 1896) Engineer Rafter submitted a voluminous report on the Genesee river storage project, on January 1, 1897, which was embodied in the State Engineerís report for 1896 as Appendix VII. The State Engineerís department held that the restrictive clause in the law, confining further investigation to the site at Mount Morris, was inserted under the misunderstanding that this site had been finally selected after exhausting the possibilities of the project and that, in view of the fact that the act which passed the Legislature in 1895, but failed of approval, had left the question of location open, while providing a sum for further research, a fair interpretation of the intent of the law would still leave the question of the best location to be determined by further investigation, and with the concurrence of the Comptroller this view governed the work.

A new site at Portage was examined. By reason of its greater elevation five hundred feet of additional head could be utilized for commercial purposes. The solid rock foundation, found here at surface, and the narrower section of the canyon presented a saving of more than fifty per cent over the Mount Morris site in the cost of masonry for dam alone, and a dam one hundred and eighteen feet in height at this location, estimated to cost one million dollars, would provide storage for fifteen billion cubic feet as against a storage capacity of seven billion three hundred and seventy million cubic feet at the Mount Morris site. From a financial point of view, computations were made as to the relative power to be furnished by both the Mount Morris and the Portage projects and their value at the City of Rochester, by which the former was shown to be commercially impracticable and only to be constructed and maintained at an annual loss of many thousand dollars, while the Portage plan exhibited a net income of several hundred thousand dollars. 28

A careful examination of Mr. Rafterís report, together with the prior reports upon this gigantic scheme for storage and regulating works, leads the average reader to but one conclusion. While the proposition was admirable in plan, and entirely feasible from an engineering standpoint, its salient feature was its proposal to restore to the mill owners of Rochester and vicinity the volume of water which came to their wheels in years long gone by, and of which they were deprived, not so much by its diversion for canal purposes as by the deforestation of the catchment basin of the upper Genesee by owners of forest lands, and for this loss the State was asked in this manner to provide compensation. For the use of the canals it would appear that the existing works at Rochester would furnish ample supply.

Sundry bills were introduced in the Legislature of 1897, to prevent extortion and combination in transferring State canal grain, discriminations in freight rates against shippers by canal and to provide for State elevators. One of these, by Mr. Koehler, was to submit to the people at the next November election a proposition to issue three and a half millions in bonds, and with the proceeds buy all boats, harbor-tugs and Hudson river tow-boats used in the transportation of flour, grain and merchandise, and all dry docks and boat yards used in the repair and building of canal, tow and tug-boats plying between Buffalo and New York along the Erie canal and Hudson river, the ownership to be vested in the people and to be operated by the State, in order to cheapen transportation to the minimum rate between producer and consumer. These various measures were referred to committees and apparently died there. 29

Another change was made in the statute regulating chattel mortgages on canal-boats and craft, by section 92 of chapter 418, by which they were henceforth to be filed in the office of the Comptroller and not elsewhere.

Chapter 566 provided for a tax of nine and one-half hundredths of a mill, out of the proceeds of which three hundred and sixty thousand dollars was to be apportioned equally between the three divisions of the canal for extraordinary improvements and repairs, and fifty thousand additional for installing electric communication. Chapter 595 provided for the leasing of surplus waters of the improved canals at the discretion of the authorities. Chapter 415, known as the "labor law," gave preference to citizens of the state for employment upon public contract work, including the canals.

Under the sundry civil act of June 4, 1897, the President, on July 28, appointed a United States Board of Engineers on Deep Waterways, consisting of Major Charles W. Raymond, Corps of Engineers, U.S.A., Alfred Noble and George Y. Wisner. During this year and the three years following, appropriations were made, aggregating $485,000, which were expended by this board in exhaustive surveys of the waterways and routes through the Great Lakes and thence to tide-water. The resulting report of this board was presented to Congress on December 1, 1900. The lines examined by this board across New York State were: from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario; from Oswego, by way of the Oswego-Oneida-Mohawk valleys to the Hudson; and by way of the St. Lawrence river to Lake St. Francis, thence across the country to Lake Champlain and thence through Lake Champlain and the upper Hudson to tide-water. Estimates were made for both a twenty-one-and a thirty-foot depth on each of these routes.

The route from the Hudson river to Lake Ontario was divided into three portions which were as follows: that portion from Oswego to Herkimer, which was in charge of Albert J. Himes; [see errata] that portion from Herkimer to the Hudson, which was in charge of David J. Howell; and the subject of water-supply, which was in charge of George W. Rafter. These surveys and estimates included two projects through the Mohawk valley, one for a high level canal across the summit near Rome, and the other for a low level, cutting the summit down to the regulated level of Oneida lake. 30

Canal navigation opened May 8 and closed December 1, two hundred and eight days. Lake Erie was open from April 6, and the Hudson river from April 29 to December 7. The season was again an unusually dry one throughout the drainage area for supplying the canals, but owing to improvements recently made in storage capacity, no hindrance to navigation on the main canals occurred.

There were 2,332 boats navigating the Erie canal, of which 1,117 were grain carriers, and were rated as first, second and third-class. The others were classed as carriers of coal, lumber and other coarse freight. Most of them were old and rotten and required only a slight accident to sink them. Very few new boats had been built during the past ten years. Many were propelled by mule-power, such as had been in vogue for many years. Practically the only improvements were a few steam-propelled fleets. There were registered during the year eleven boats of two hundred and fifty tons, three boats of two hundred and forty tons, and one each of two hundred and twenty-five and one hundred tons.

The aggregate payments for ordinary repairs and maintenance for the year ending September 30, 1897, were $904,309.48, as against $1,006,453.70 for similar payments for the previous year. The total receipts of flour and grain at New York by all routes during the season of navigation, May 1 to November 30, 1887, were 140,030,101 bushels, of which the canals brought 20,998,561 bushels or 14.99 per cent. The whole number of tons of freight carried on the canals in 1897 was 3,617,804, of which more than two-thirds was east-bound and about one-half was through freight. Of the total tonnage the Erie canal carried 2,584,916. The tendency seemed to be toward a larger way freight business and a decrease in through freight.

The season was not a prosperous one for boatmen. Rates were unusually low and many owners preferred to tie up their boats rather than accept the rates offered. The principal causes were alleged to be deterioration of the canal prism, non-improvement of boats and motive power and excessive terminal charges at Buffalo and New York. The earnings of an elevator at Buffalo for handling a cargo of 200,000 bushels of grain at prevailing rates would be about $2,650. A single elevator, costing a quarter of a million dollars, was known to have paid for itself in a single year. Nearly all of them were under the control of a trust and received a share of the profits, whether operating or not. The Superintendent of Public Works considered that the better remedy would be to control these excessive charges by statutory limitation rather than to provide State elevators. 31

In his report at the beginning of 1898, State Engineer Adams also strongly presented the necessity of curbing excessive terminal grain charges in order to supplement the improvements of the physical features of the canal, claiming both to be necessary to the restoration of the commercial supremacy of New York City. In support of this argument numerous references were made to the report, already noted, of Major Symons to the Federal Government. 32

During the latter part of 1897 it began to be fully realized by those connected with the work of canal improvement and to be generally understood by the public that the whole amount of contemplated work could not be accomplished with the nine million dollars, and with these reports came rumors of alleged frauds and extravagance in the administration and prosecution of the undertaking.

At the beginning of 1898, Governor Black at once called the attention of the Legislature to the canals, saying that the work of deepening them, for which an appropriation of nine million dollars had been made, could not be completed for that sum. That amount had been disposed of and less than two-thirds of the improvement had been provided for. The Governor thought that the completion of the work should be considered as the last half of the same project, but it was a subject of the utmost importance and a problem too serious to be decided by the Legislature. The people had voted for the nine million appropriation and if a further sum was needed it should also receive the peopleís sanction.

The Governor asserted that New York City was not getting her share of commerce and intimated that this might be on account of a too narrow policy with reference to terminal facilities. If this were so, the State should open such facilities in New York harbor as would draw every pound of freight which would naturally come there. A broad and liberal policy was demanded, and competition -- especially Canadian -- should be feared and met. The Governor also advised the creation of a commission to examine into the cause of the decline and the means of reviving the commerce of New York. 33

On January 12, 1898, the State Engineer and the Superintendent of Public Works addressed a joint communication to the Governor stating that the original appropriation of nine million dollars would be insufficient to complete the work and that another large sum would be needed. This would require the submission of the question to popular vote, and in order that such vote might be intelligently taken, they recommended that a committee of examination and estimate, composed of the ablest and most impartial citizens, be appointed to consider the whole subject. 34

In both Senate and Assembly, bills were introduced relative to the appointment of an investigating committee to inquire into the expenditure of the nine million-dollar appropriation. Numerous amendments and substitutions were made and a bill of this nature finally became a law, known as chapter 15. 35 This bill, passed February 23, provided for the appointment by the Governor of a commission of from five to seven citizens to fully investigate and report upon the "nine million" improvement and all matters connected therewith. This report was to be made to the Governor by June 1, 1898, unless he should extend the commissionís time to July 1, and was to be open to the public and to be transmitted by the Governor to the next Legislature.

The commissioners appointed by Governor Black at once organized as follows: George Clinton, chairman; Franklin Edson, secretary; Smith M. Weed, Darwin R. James, Frank Brainard, A. Foster Higgins and William McEchron, commissioners. The commission appointed Edward P. North, consulting engineer, Lyman E. Cooley, advisory engineer, and Abel E. Blackmar, counsel. In addition to taking testimony, the commissioners personally inspected the most important points, and their engineers examined the entire line of the Champlain, Erie and Oswego canals. Their report (referred to later) was dated July 30, 1898.

But few other laws of importance affecting the canals were passed at this legislative session. Chapter 506 imposed a seven-hundredths of a mill general tax, from the proceeds of which three hundred and fifty thousand dollars was to be available for extraordinary repairs and improvements on the canals. Chapter 644, passed April 29, authorized the appointment of a commission of five by the Governor, to inquire into the condition of the commerce of New York, the causes of its decline and means of its revival, to summarize their conclusions, suggest advisable legislation and to report by January 15, 1899.

Work under the general improvement plan was stopped suddenly just as canal navigation was about to be resumed in the spring of 1898, and was left in such an unfinished state that the resources of both the ordinary and extraordinary funds were strained to the utmost limit to enable navigation to be resumed at all.

On July 30 the commission appointed to investigate the nine million-dollar improvement reported to Governor Black, their time having been extended to August 1, by the Legislature (chapter 327). Appended to their report 36 was one to the commissioners from their consulting engineer, Edward P. North, and their advisory engineer, Lyman E. Cooley. Thereupon Governor Black appointed Judge Edwin Countryman to examine the report, to determine whether legal proceedings -- civil or criminal - should be begun, and if so, against whom and in what way.

The report contained numerous criticisms of both State Engineer Campbell W. Adams and Superintendent of Public Works George W. Aldridge. Thereafter, on September 12, Mr. Adams addressed a communication to Governor Black which he termed a "statement on his part" in reply to certain features of the report of the investigating commission. This explanatory statement was published in the State Engineerís annual report for 1898. 37

The publication of these documents was made the basis of an acrimonious controversy which was taken up by the public press and colored according to the various attitudes of the writers upon the question of canal improvement. It cannot be disputed that this was a critical period in the history of the canals. The people of the state had generously authorized the appropriation of a sum which they had been told was sufficient to complete the improvements desired. Their sense of disappointment at the results was keen and the blame fell heavily. The criticism by the commission was of dual nature. The State Engineer was blamed for the fact that the nine million-dollar appropriation did not cover the cost of the proposed improvement. This involved the charges of insufficient estimates, lack of foreknowledge of the peculiar difficulties encountered in construction, and improper classification of materials excavated. The Superintendent of Public Works was largely censured for extravagant and unnecessary expenditures during construction.

Adverting to the period of the Constitutional Convention in 1894, we notice that when the canal amendments were under discussion, the State Engineer was called upon for estimates. But no available data were at hand. For several years prior the State Engineers had urged the Legislatures to appropriate money for a thorough survey for contemplated improvements, but without success. However, upon the inadequate information at hand and the notes of the old Van Buren survey (1876), which the investigating commissioners themselves examined and pronounced worthless for the purpose, the estimate was made and delivered to the Convention within twelve days. It was expressly stated to be but a guess, assuming all conditions to be favorable, and was not nine million but eleven million five hundred and seventy-three thousand dollars, with another million needed for repairing and rebuilding walls. The Legislature, later, without consulting Mr. Adams, as he states, reduced the amount to an even nine million dollars, as being all that the people would be willing to authorize at the time. The statute required the work to be commenced within three months.

The department endeavored to rush through a complete new survey, which could not be so thorough as the conditions demanded. The result of the survey was that the estimates were raised to thirteen and a half millions, exclusive of engineering, advertising or inspection, or fifteen millions in all. Later this was revised and made sixteen million dollars. For the discrepancy between the ever-increasing estimates and the appropriation of nine million dollars, Mr. Adams was at the time severely criticized, though always denying the responsibility. Later developments seem to have amply justified his denial and to place the blame upon the Legislature, where it justly belongs. In speaking of this subject, Governor Theodore Roosevelt, in a message transmitting the report of the New York Commerce Commission to the Legislature on January 25, 1900, said in his usual direct and emphatic style: "I desire especially to call your attention to that portion of the Commerce Commissionís report which shows the main source of the trouble over the nine million dollar expenditure for improvements under the Act of 1895. The Commerce Commissionís report makes it perfectly clear that there never was sufficient authority, or indeed any authority for supposing that this nine million dollars would be enough to complete the work, and that a sum was named which was entirely insufficient. It was doubtless believed to be easier to get the small sum than a large one." 38

The original contracts were let upon the unit system, which has been in vogue for many years upon public works -- that is, so much per cubic yard for rock or earth actually excavated. There always have been and always will be advocates of the "lump sum" method of bidding, as opposed to the "unit system." Mr. Adams summed it tersely by saying that so long as the State got value received for every yard paid for, it made little difference whether the original estimates were too high or too low, the final estimate, upon which payment was based, showing just what the original estimate would have been, if absolutely correct.

During the period of construction, when the water in the prism was necessarily entirely drawn off, at some places for the first time in many years, the footings of the banks and walls were thus exposed to the action of frost and floods. Imperfections in the work of former years were revealed, structures were further disintegrated, unexpected difficulties developed and the cost was largely increased. Especially was this the case through Buffalo and other cities.

The investigating commissioners stated that the new work was well done, that prices bid were reasonable and that the contracts were let to the lowest bidder. They called attention to the high value of the canals as the cheapest means of transportation, both in the past and at present, and as a freight regulator. They severely condemned the dual system of control and advised that the sole responsibility be vested in one department, preferably that of the State Engineer. They recommended the continuation of the improvement, regardless its cost, with more accurate studies of the conditions and specifications; also that proper compensation be exacted from parties using surplus water and that none but surplus water be so used; that the practice of erecting structures on canal lands, and of emptying sewers therein, be stopped; and that an experimental pneumatic lock be built only at Newark. The commission further called attention to the fact that the entire cost of construction, enlargement and maintenance of the canals up to 1885 was $102,345,123, while the total tolls received were $134,648,900, to which could be added the enormous aggregate representing their indirect influence on the prosperity of the State.

On July 1, 1898, Engineer G. W. Rafter, acting under his instructions of December 31, 1897, made a final report to the State Engineer upon the results of further tests as to the strength of concrete blocks, in connection with the Genesee storage project. His conclusions were that the successful use of concrete required the oversight of a man of high intelligence, thoroughly versed in the possibilities of the material, that all thumb rule methods should be avoided and that dry mixing and thorough ramming should be enforced. 39

Navigation on the canals opened May 7 and closed December 10, 1898. The Hudson river was open from March 14 to December 12, and the lake ports after March 25. The season again did not prove a prosperous one to the boatmen. But four new boats were registered, one each of one hundred and fifty and one hundred and twenty-five tons, and two of one hundred tons. The total tonnage of the canals for the year was 3,360,063, of which 2,314,050 tons were east-bound and 1,046,013 tons were west-bound. Of through freight 1,573,227 tons were carried, of which 1,111,699 tons were east-bound. Of the gross tonnage, the Erie canal carried 2,338,020 tons. The aggregate payments for ordinary repairs and maintenance for the fiscal year of 1898, were $923,903.67.

On November 28, 1898, Judge Countryman filed with the Governor his report and findings upon the report of the canal investigation commission. Thereupon the Superintendent of Public Works, George W. Aldridge, requested the Governor to suspend him from his office, pending the result of the judicial inquiry into his official acts. On December 2, Governor Black so suspended him and directed the Attorney-General to present his case to the grand jury. The Attorney-General, under these directions from the Governor, assigned Benjamin J. Shove, one of his deputies, to ascertain when, where and what crimes had been committed in connection with the canal enlargement and to proceed with prosecutions. 40

At an early date in 1899, after submitting the report of the commission and Judge Countrymanís conclusions thereon to the Legislature as required by law, Governor Roosevelt, impressed with the importance of the matter, appointed additional counsel, Messrs. Austin G. Fox and Wallace Macfarlane, to assist the Attorney-Generalís office in further examination as to whether the case should be submitted to a grand jury.

On April 7, Messrs. Fox and Macfarlane wrote to the Governor asking an immediate appropriation to enable them to further examine witnesses, and this communication was at once sent to the Legislature by the Governor, with the request for immediate attention. 41 In compliance, the Legislature, on May 2, by chapter 495, appropriated twenty thousand dollars for the expenses of inquiry into matters pertaining to the awarding and performance of canal improvement contracts, with the proviso that the special counsel should report progress within three months thereafter. Also, chapter 569 appropriated five thousand dollars for salary and expenses of Benjamin J. Shove, Deputy Attorney-General.

After due consideration, Messrs. Fox and Macfarlane made their final report to the Governor. In substance they found that most of the matters under consideration were barred by the statute of limitation and as to the remaining matters, while there was evidence of conduct justifying severe criticism and public indignation, there was not enough to warrant criminal proceedings. This report was attached to the Governorís annual message for 1900.

In reply to a Senate resolution of January 19, 1899, State Engineer Edward A. Bond and Superintendent of Public Works John N. Partridge, on February 6, submitted a tabulated statement of all contracts let under the provisions of the "nine million" act, together with the existing status of those unfinished and the amount and time required to finish them, the figures being given from department records. The total amount paid on contracts was $7,238,795.08, the amount retained, $694,162.58, making total paid or due on contracts, $7,932,957.66. There had been paid for advertising, $92,320.70, inspection, $180,501.36, disinfectants, $6,482.49, miscellaneous, $227.44, engineering, $820,000. The total of all payments made or due was $9,032,489.65, making a deficit of $32,489.65. To this deficit should be added the estimated amount required to finish contracts, $4,430,007.88, engineering $236,600, and inspection $101,400, making the total amount required to complete awarded contracts, $4,800,497.53. One more season would be required to complete most of the contracts, a few others would require two seasons, while several would apparently take three seasons to complete. 42

On May 5 the Legislature, by chapter 544, enlarged the powers of the canal board in settling unfinished contracts made under this act, authorizing them to terminate existing contracts, and to pay off the contractor, including the ten per cent reserved. Few other canal laws were passed at the session of 1899. Chapter 208 provided a seven-hundredths-mill general tax, from the proceeds of which three hundred and fifty thousand dollars was set aside for extraordinary repairs and improvements of mechanical and other structures, and works connected with the canals.

On January 18, 1899, the commission on commerce of New York, appointed by Governor Black under the act of April 29, 1898, and consisting of Charles A. Schieren, Andrew H. Green; C.C. Shayne, Hugh Kelly and Alexander R. Smith, reported that, owing to a defect in the statute under which they were acting, they were left without funds to pursue the investigation properly. They recommended a continuance of the committee under improved conditions. 43 Governor Roosevelt, in his annual message, also endorsed this recommendation, and by chapter 494, the commission was given an extension of time until November 1, 1899, in which to make final report and the sum of fifteen thousand dollars was appropriated for their expenses.

Chapter 519, passed May 4, authorized the canal board to permit the construction of a pneumatic lock and canal connections, in place of the "sixteens" at Cohoes at the expense of private parties and provided for their subsequent rental or purchase by the State upon completion, at the option of the canal board, if found upon due trial to operate satisfactorily. The minutes of the canal board do not show that the required permit was subsequently granted.

Governor Roosevelt, on March 8, appointed a new committee, consisting of Gen. Francis V. Greene, chairman, Frank S. Witherbee, Major Thomas W. Symons, U.S.A., John P. Scatcherd and Geo. E. Greene, who, together with Edward A. Bond, State Engineer, and John N. Partridge, Superintendent of Public Works, were to consider the whole canal question and report upon the proper policy to be pursued by the State in the future. By this means the Governor was enabled to obtain an opinion from prominent engineers and business men who, after thorough and careful investigation, could be relied upon to give an able and unbiased decision, and one which, from the personnel of the committee, would be considered authoritative by the general public. The appointment of such a committee was most opportune at this time. The inadequacy of the canals to meet the growing needs of commerce had long been conceded. The first enlargement was scarcely completed in 1862, before the need of further improvements was realized, and for years attempts had been made to reach a solution of the canal problem, until in 1895, the question was supposed to be settled for many years. Now, after the miscarriage of that project, opinions, both expert and popular, were so varied that a guiding hand was needed. The people had evinced a willingness to approve whatever undertaking was necessary, if an adequate policy were designated, but they were in no mood to temporize or experiment and this office of guidance the committee fulfilled. From its appointment may be dated the beginning of the Barge canal enterprise, although a very similar scheme had been advocated by State Engineer Martin Schenck in 1892.

The Erie canal was opened to navigation on April 26, 1899, and closed on December 1, making the longest season since 1882. The season was a prosperous one for boatmen. Rates were remunerative and on some freights unusually high. More boats could have been used to advantage, but the building and registry of new ones seems to have ceased. The Hudson river opened April 17 and closed December 15, while the lake was free from ice on April 28.

The cost of ordinary repairs and operating expenses on the canals of the state for the fiscal year ending October 1, 1899, was given as $867,148.41. The total receipts for flour and grain by all routes at New York, from May 1 to November 30, were 125,464,839 bushels, of which the canals carried about thirteen per cent. The total tons of freight carried on the canals during 1899 was 3,686,051, of which 2,425,292 tons went eastward and 1,260,759 tons westward. There were 1,692,972 tons of through and 1,993,079 tons of way freight. Of the through freight 1,164,605 tons went eastward, and 528,307 tons westward and of the way freight 1,260,627 tons went eastward, and 732,452 tons westward.

On January 25, 1900, the New York Commerce Commission, appointed by Governor Black in 1898, and continued under a legislative act of 1899, submitted to the Governor a voluminous report, which was transmitted by him to the Legislature and published as an Assembly document of that year. 44 The report assigned, as a leading cause of the decline, the differential rates on all western traffic. These rates had been agreed upon in combination between trunk line railways to the seaboard, discriminating against New York in favor of other Atlantic seaports. As a contributing cause, the report mentioned the excessive terminal charges. The commission especially censured the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad Company for participating in such agreement, and demanded its withdrawal therefrom.

The commission recommended, as the best remedy, that the State should complete the improvement of its canals under the nine million plan, by the further expenditure of a sum not to exceed fifteen million dollars, after the submission of a bonding bill for that purpose to the people at the next election. The commission also advised that suitable terminal piers and facilities should be provided both at Buffalo and New York exclusively for canal traffic; that elevator charges should be reduced to a maximum rate of one-half cent per bushel on grain; that the limitation of the capital stock of transportation companies to fifty thousand dollars should be repealed; that the City of New York should endeavor speedily to supply the demands of commerce for modern piers, and that the Legislature should aid the effort in every way practicable.

The committee appointed by Governor Roosevelt on March 8, 1899, to advise as to the future canal policy of the State, continued its investigations during that year and reported to the Governor under date of January 15, 1900. The report showed a very exhaustive study of the whole question and was accompanied by many maps and tables, the records of public hearings and a large correspondence with those who were qualified to advise on the subject. After careful consideration the committee most emphatically recommended that the canals should not be abandoned, [original text has "abandone".] but that the Erie, Champlain and Oswego canals should be enlarged -- the Erie to a size suitable for thousand-ton barges, the Champlain and Oswego to a nine-foot depth, according to the 1895 project. It also recommended that the Black river and the Cayuga and Seneca canals should be maintained as navigable feeders, but not enlarged; that the scheme for a ship canal was a proper subject for consideration by the Federal Government, but not by the State of New York; that the money for the improvements should be raised by bond-issues to be paid by taxes upon the counties bordering on the canals, the Hudson river and Lake Champlain; and that $200,000 should be immediately appropriated for making detailed surveys in order to consummate the proposed project. As the efficiency of the canals depends upon their management as much as upon their physical size, the committee also recommended that large transportation companies for handling canal business should be encouraged by removing all restrictions as to the amount of capital; that steam or electric propulsion and mechanical power for operating gates and valves and for moving boats in locks should be employed; that State forces on public works should be so organized on a permanent basis as to afford an attractive career to able men; and that the laws should be so revised in regard to the letting of contracts as to make impossible a repetition of former unfortunate results.

If enlarged as recommended, the Erie canal would be of a size suitable for the use of boats one hundred and fifty feet long, twenty-five feet wide and drawing ten feet of water. Such boats were estimated to carry one thousand tons each and a four-boat steam fleet would carry thirty-nine hundred tons, or one hundred and thirty thousand bushels of wheat. The prism would have a depth of twelve feet, a bottom width of seventy-five feet, with side slope of one on two. The locks would be three hundred and ten feet long in the clear, twenty-eight feet wide, with eleven feet of water on the sills. The proposed route followed very closely the line on which the Barge canal is at present being built, and which will be found described a little later in this chapter. The committee estimated that the Erie could be thus enlarged for $58,894,668, which, together with $818,120 for the Oswego and $1,824,000 for the Champlain, would make $61,536,788, or in round numbers, $62,000,000, as the total expense of completing their recommended improvements.

The Legislature considered this report favorably and on April 12, 1900, enacted chapter 411, directing the State Engineer to cause surveys, plans and estimates to be made for improving the Erie, Champlain and Oswego canals as recommended by the committee on canals, except that an alternate project was added for enlarging the Oswego to the same size as proposed for the Erie. A sum of $200,000 was appropriated for doing this work, which, by action of the canal board, was afterward made to include the survey and estimate for a canal between Lakes Erie and Ontario around the falls of Niagara. A large force of engineers was immediately placed in the field and careful topographic surveys were made, together with frequent borings and a special study of water-supply, conducted by Mr. Emil Kuichling. When the field work was finished, the men were transferred to the office and complete plans and estimates were prepared in time to report to the Governor on February 12, 1901. Much of the territory along the lines of the proposed improvements had recently been traversed by the Deep Waterway surveys, and, as the results of these surveys were made available to the State by the Federal Government, the preliminary work was accomplished economically and expeditiously. The plans for the Champlain canal were all made from former surveys. The State Engineer associated with himself a company of eminent engineers, as an advisory board, and many others, for making surveys and plans, who were experts in their various fields of work, so that a general confidence was established in the accuracy and completeness of the resulting plans and estimates.

Special appropriations at this time were again becoming numerous. In most cases the work was required to be done under the supervision of the Superintendent of Public Works. Of these special canal works, eighteen contracts were completed during 1900, at a total cost of $184,293.52, exclusive of engineering, on which the original estimates were $229,127.88. Fifty-eight pieces of work were authorized by special appropriations. Thirty-three of these were placed under contract, and twenty-five were processed on State force account. Chapter 311, passed April 6, 1900, provided the usual $350,000 for extraordinary improvements on canal structures and works.

As told more fully elsewhere in this volume, for several years disastrous breaks had occurred in the Forestport feeder, which were believed to be of malicious origin. These breaks, in 1897-8-9, cost the State over one hundred and thirty thousand dollars for repairs. With the approval of the Governor, the aid of Pinkerton detectives was obtained and as a result thirteen indictments in connection with the matter were found, and a salutary lesson was administered.

Canal navigation opened April 25, and closed December 1, but the last east-bound boats were delayed by a break near Rome until December 10. The Hudson river was open to navigation from April 9 to December 11. The total receipts of grain and flour by all routes at New York, from May 1 to December 1, 1900, were 105,715,669 bushels, of which the canals brought 13.33 per cent. Expenditures for maintenance and ordinary repairs for the fiscal year were $959,896.63, as against $867,148.41 for the previous year. The Superintendent attributes the increase to the operation of the eight-hour law, which largely increased pay-rolls, especially for bridge and lock-tending.

The total tonnage for 1900 was 3,345,941, as against 3,686,051 tons for the previous year, a falling off of 340,110 tons. Of the total freight carried 2,115,151 tons went eastward and 1,230,790 tons westward. There were 1,362,550 tons of through and 1,983,391 tons of way freight. Of the through freight 857,607 tons went eastward and 504,943 tons westward, and of the way freight 1,257,544 tons went eastward and 725,847 tons westward. The decrease was probably attributable to a rate war between boatmen and shippers, many boats being tied up at Buffalo awaiting higher rates; also to the late opening of lake navigation (April 23), and to the coal strike which reduced shipments of that article, especially on the Champlain canal. Another important reason was the unsettled canal policy, under which boat-building had ceased and many of the existing boats had become so dilapidated that some were obliged to go out of commission, while others were unable to get grain insurance.

In 1900 there was another general discussion of the canal question among prominent engineers. This was provoked by a paper presented by Mr. Joseph Mayer, which was published in the October proceedings of the American Society of Civil Engineers, entitled "Canals between the Lakes and New York." At the same time Mr. George Y. Wisner presented another paper entitled "Economic Dimensions for a Waterway from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic." These papers treated the subject very fully and were discussed at length in the proceedings of November and December, 1900, by Major T. W. Symons, Archibald A Schenck, Thomas C. Clarke, Edward P. North, Thomas Monro, Frank A. Hinds, Elnathan Sweet, W. Henry Hunter, Theodore G. Hoech, Alfred Noble and Lewis M. Haupt. The papers were further discussed in the proceedings for February, 1901, by other members; Rudolph Hering, George Y. Wisner, R. P. J. Tutein-Nolthenius, Joseph Mayer and George W. Rafter.

On February 12, 1901, State Engineer Edward A. Bond submitted to the Governor a full and complete report 45 of the surveys of the previous year, together with estimates for a thousand-ton barge canal by several different routes from the Hudson river to the lakes. On March 15 Governor Odell presented this report to the Legislature with a special message, summarizing routes and costs, which appeared as Senate Document No. 38.

The first route proposed was by way of the Mohawk and Seneca rivers, the distance from Troy to Buffalo being 342.56 miles, including improvements to the Oswego canal from Three River Point to Oswego, nine miles, and of the Champlain canal from Troy to Whitehall, at a total cost of $78,496,446, from which estimate the value of abandoned lands is to be deducted, amounting on the Erie canal to $1,941,380, and upon the Champlain canal, $22,620, which leaves the net cost, $76,532,446.

The second route proposed was by way of the Mohawk and Oswego rivers, via Olcott to Buffalo, using Lake Ontario, a total distance of 338.66 miles, with improvements to the Erie canal, amounting to $46,765,755, the Oswego canal, amounting to $5,170,129, and the Champlain canal at a cost of $4,750,608, making the total gross cost of $56,686,492, from which should be deducted the estimated value of abandoned lands on the Erie canal, $1,953,202, leaving the net cost, $54,708,729.

The third route was by way of the Mohawk and Oswego rivers and Lake Ontario, via Lewiston to Buffalo, a total distance of 347.57 miles, at a total cost of $48,984,220 for the Erie canal, $5,170,129 for the Oswego canal, and $4,750,608 for the Champlain canal, making a total cost of $58,904,957, from which should be deducted the value of abandoned lands, as in the case of the Oswego-Mohawk route, leaving the net total cost, $56,926,744.

The fourth route was by way of the present canal -- modified -- from Troy to Buffalo, 347.66 miles, at a cost of $81,578,854; for improving the Oswego canal, $1,481,012, and the Champlain canal, $5,787,929, making a total cost of $88,847,795, from which should be deducted the estimated value of abandoned lands on the Erie canal, $1,530,225, leaving the net cost, $87,317,570. To this total should be added the improvement of the Hudson river from Troy to Watervliet, $737,683, and improving Black Rock harbor, $538,051, a total of $1,275,734. These latter items were to be added to each of the above estimates if the United States Government should not do this work.

For the purpose of comparison the Governor presented the cost of completing improvements of the canals along the nine million-dollar plan, under the act of 1895, as amounting to $19,797,828, divided as follows: the eastern division, $5,825,386; the middle division, $2,086,987; the western division, $7,060,950; the Champlain canal, $2,689,117; and the Oswego canal, $2,135,388. To this should be added the value of the property taken or injured by this improvement.

As to the comparative cost to the taxpayers it was assumed that money could be borrowed at three per cent interest and that the constitutional bond limit was eighteen years. Providing for a reduction of one-eighteenth each year, the total cost, including interest, would be:

By the first plan, $97,197,206.42, or $5,399,789 annually.

By the second plan, $69,479,514, or $3,859,973 annually.

By the third plan, $72,296,964, or $4,016,498 annually.

By the fourth plan, $110,893,313, or $6,160,739 annually.

By the fifth plan, $25,143,241, or $1,396,846 annually.

Upon the estimated valuation of that date, the total cost per $1,000 would be: first plan, $17.14; second, $12.25; third, $12.74; fourth, $19.55; fifth, $4.43.

These plans and estimates, as required by chapter 411, Laws of 1900, provided for not less than twelve feet of water throughout the Erie canal for boats of one hundred and fifty feet in length by twenty-five feet in width and of ten feet draught, with a cargo capacity of about one thousand tons; the bottom width to be not less than seventy-five feet, with a cross-sectional area of not less than eleven hundred and twenty-five square feet, except where modified through cities, and not less than eleven feet of water was to be provided for in locks and over structures. The locks were to be three hundred and ten feet in the clear, by twenty-eight wide. The Oswego canal was to have nine feet of water in the prism generally, eight feet of water in locks and over structures. Locks were required to pass boats of eight feet draught, seventeen and one-half feet wide by one hundred and four feet long. Other plans were also made to correspond with the dimensions of those of the Erie canal. The Champlain canal plans provided for deepening to seven feet of water, to pass boats having six feet draught, ninety-eight and one-half feet long by seventeen and one-half feet wide. 46

These various plans were subsequently considered by the Legislature, but differences of opinion among the friends of canal improvement prevented concentration upon any one plan. In the Senate a bill to issue bonds not to exceed twenty-six million dollars for canal enlargement and to submit the proposition to the people in November following was advanced to a third reading but was finally tabled. In the Assembly a similar bill was introduced, but failed to get beyond second reading. 47

By the terms of chapter 81, Laws of 1900, additional powers had been conferred upon the canal board, enabling it to hear, determine and settle in full contractorsí claims connected with the cessation of work under the "nine million" act. Under this act sixteen contractors filed claims up to the close of 1901, the claims amounting to $1,038,870.98. These cases were heard and awards made amounting to $473,458.59, or about 45 Ĺ per cent of the claims. 48

Carrying out the policy of the previous half dozen years, chapter 347 appropriated $325,000 for extraordinary repairs and improvements of existing mechanical and other structures and works connected with the canals.

In reply to a Senate resolution of March 20, the Superintendent of Public Works informed the Senate that at that date there were 207 ĺ miles of poles and wires strung along the banks of the canals within the "blue line," and in addition twenty-eight miles of this were duplicated by other lines. These were for the various purposes of power, light, heat and message transmission, most of them by formal permits from the department, but not all; some probably by verbal permission of division and section superintendents. 49