AFTER Marco Paul and Forester had had their dinner, they went forth with feelings of eager interest in quest of the aqueduct.

"How do you know where to find it ?" asked Marco.

"There can not be much difficulty in finding it, I think," said Forester; "for such a work must be a very conspicuous object in such a village as this."

They were on the north side of the river. The village, however, extended to both sides. As they walked along they could see the river tumbling over the rocks, wherever a street or an interval between blocks of buildings opened a view. After following the line of the railroad a short distance, they turned down toward the river by a broad street, which seemed to be a great thoroughfare, and which Forester therefore thought would probably lead to a bridge.

He was right in this conjecture. The street conducted him and Marco between buildings, which seemed to be mills, machine-shops, and foundries, and at length it came to a bridge which led over what appeared to be a canal. "Here is the canal," said Marco.

"Not the Erie canal," said Forester.

"Why not ?" asked Marco.

"Because," replied Forester, "that is on the other side of the river."

"This is a canal, at any rate," said Marco.

He judged that it was a canal by its being lined with walls of stone in some places, and by the regularity of the bank in other places, showing that it was an artificial construction. On farther examination they found that it was parallel to the river and on a much higher level, and they observed that there was a current in the water.

"Perhaps," said Forester, "this may be the water which goes in over the aqueduct and feeds the canal. Let us go on and see."

So they walked on. Presently there came into view the deep and rocky bed of the Mohawk itself, with what Marco at first thought were two bridges leading over it. The two bridges were very near each other, side by side; so near that it seemed to Marco that he could throw a stone from one to the other.

In a moment, however, he perceived that they were not both bridges; for the lower one, instead of having a roadway passing over upon it, had only the water of a canal. There was a kind of a narrow walk on each side, but nothing but water in the middle. " That must be the aqueduct," said Forester.

"Yes," said Marco; "let us go and see it."

So they left the street and went across a vacant piece of land between two piles of boards, until they came to the bank of the canal. They found now that the canal which they had observed before they came in sight of the aqueduct, turned its course as soon as it passed under the bridge where they had crossed it, and expanded into a broad basin, and from one side of this basin there was a sort of branch which led directly to the aqueduct, and so across the river.

"Now," said Forester, "we will go on to the aqueduct, and walk along one of the sidewalks, and then we shall see the water pouring over the aqueduct, across the river, into the Erie canal."

Marco found in this case an illustration of the truth of what Forester had told him of the value of some preliminary knowledge, to give interest and zest to traveling and observation. He was very much interested in going on with Forester to see the aqueduct. Even so slight a circumstance as the expected flow of the water across the river from north to south, instead of coming in the opposite direction, interested him strongly, on account of his having previously become acquainted with the facts and principles on which the determination of the current, as he supposed, depended.

There was a canal-boat lying in the aqueduct itself. It was a coarse-looking boat, in the form of a scow, and it was held in its place by a cable. The cable was fastened by one end to the bow of the boat, and by the other to a post set in the bank. There was a little cabin built in the stern of the boat, and a young girl was looking out at the window of it.

"Where are you going in this boat ?" said Marco to the girl.

"To Rochester," said the girl.

"When are you going ?" asked Marco.

"I don't know, sir," said the girl.

Just then, Marco, who was standing while he said this on the stone sidewalk, just at the beginning at the aqueduct, looked down between the boat and the wall, and to his great surprise he observed that the water, instead of flowing on toward the Erie canal, which was on the other side of the river, was in reality flowing away from it. It was coming toward the side of the river where they then were. He could see the direction of the current very plainly by the ripples between the side of the boat and the edge of the wall.

"Why, Forester !" said Marco, "the water is running the wrong way."

Forester looked down at the ripples which Marco pointed out to him, in silence.

"Is not the canal over that way ?" continued Marco, pointing over the river.

"Yes," said Forester, "I suppose so."

"Then the water is all running away from it. The aqueduct is emptying the canal as fast as it can, and they call it a feeder."

Forester made no reply, but looked first into the aqueduct, then over toward the canal, and then back to the basin on the other side. He did not know what to make of the case.

"Little girl," said Marco, "what makes the water in this aqueduct run the wrong way ?"

"Sir?" said the girl.

"Is not this a feeder ?" said Marco.

"I don't know, sir," said the girl.

"Hush, Marco," said Forester; and so saying, he drew him along toward the middle of the aqueduct. "Don't trouble that poor girl with your questions. It is not probable that she knows any thing about it."

"Why, cousin Forester," said Marco, "she has been sailing over it all her life, -- it's likely. I expect she lives on the canal. I wish you would let me go in and see the room in the canal-boat that she lives in."

"That you may do," said Forester, " and I will wait here until you come back."

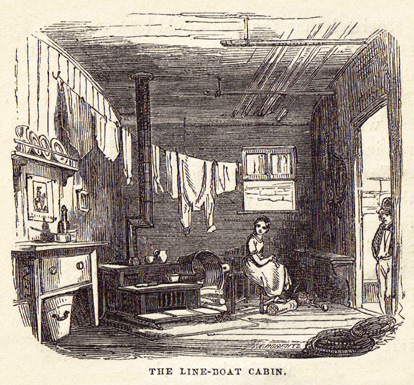

So Marco went and stepped on board of the boat, and then proceeded to the cabin door. The door was open, but he had to go down several steps to enter it. The interior was very plain, and very plainly furnished, and yet it had a cheerful and pleasant expression.

There was a stove in one corner, with a pipe, which, after being bent twice at right angles, ascended and passed out through the deck of the boat, overhead. There were some clothes hanging upon a line which was stretched across the corner of the cabin, behind the stove-pipe. This line extended from a window on one side to a nail fastened in the wall on the other. The window was open.

There was a shelf on one side of the cabin, with plates upon it. There was a little rail extending along this shelf in front of the plates, to keep them from being thrown down by the motion of the boat. Under the shelf was a picture hung against the wall, and under the picture a table. There were various things upon the table, such as a bottle, a dipper, &c. Marco examined all these things with great interest. as he stood at the door.

The window was rather high, but Marco perceived that the girl could look out at it by standing up. While Marco was standing at the door, the girl was sitting down upon a stool. Marco remained at the door a little time talking with the girl, and then he went back and rejoined Forester.

Forester and Marco then walked along upon the aqueduct sidewalk. This sidewalk was formed of large square stones, beautifully hewn, and there was a strong iron railing on the outer side of it, toward the river, so as to keep the passengers from falling off. There was, however, no railing on the inner side, that is, the side next the canal. But this was not necessary, as the water in the canal was nearly on a level with the sidewalk itself. But it was very far down from the aqueduct to the river below.

Marco stopped to lean upon the iron railing and look down. He could see the water of the river, tumbling along in a narrow rocky channel, under the arches of the aqueduct.

"I should like to be down upon those rocks with a good fishing-line," said Marco.

Forester paid no attention to what Marco was saying. He was looking at the bridge, which was full in their view a little way up the stream. The bridge was supported by two or three arches, and was built of stone, in a very substantial manner.

"Let us go around and get on the bridge," said Marco; "and then we can see the aqueduct better."

"Very well," said Forester.

"O see, what a funny house !" said Marco, pointing before them.

Forester looked in the direction which Marco indicated, and he saw a house, which was painted red and white, in small alternate squares, like a chequer-board. It was but a short distance beyond the aqueduct, and was on the corner between the canal which came in over the aqueduct, and the great Erie canal beyond. When they came to this corner they found the Erie canal before them, extending up and down, parallel to the river, as far as they could see. There was a lock very near, with a boat going through it. Forester and Marco stopped to see the boat locked through.

Forester looked around a little to find somebody whom he might ask for an explanation of the difficulty in regard to the current of water over the aqueduct, but he did not succeed. The man who had charge of the lock looked very rough and ill-natured, as was very often the case, in respect to workmen along the canal. Besides, as he was apparently only a common laborer, Forester thought it was very probable that he would not know any thing about it.

After the boat had been locked through, Forester and Marco walked along the bank of the canal until they came opposite to the bridge which they had seen just above the aqueduct. They walked over upon the bridge, and took a view of the aqueduct from it.

"I confess I don't see how it happens that the water is flowing out over the aqueduct," said Forester.

"Nor I," replied Marco.

"That must be the aqueduct, certainly," said Forester, though he spoke in a tone of doubt.

"I'll look at the description again," he continued; and so saying, he took out his little map, and spread it open upon the railing of the bridge, so that he and Marco could see it.

He found a brief description of the Erie canal upon a corner of the map. There were several aqueducts named in this description, and among others the one at Little Falls was particularly referred to.

"I will read the description," said Forester, "and you may see whether it corresponds to this aqueduct."

"'Length two hundred and fourteen feet,'" said Forester, reading from his map.

"Well," said Marco; "but I don't know whether that is correct or not, for I can not tell how long this aqueduct is."

So Forester looked up, in order to estimate the length of the aqueduct before him, by his eye. He said he thought it was as much as two hundred and fourteen feet long. "'Constructed of hewed limestone,'" continued Forester.

"The stones are hewed," said Marco, "but I don't know whether they are limestone or not."

"I presume they are limestone," said Forester, -- "'supported by three arches.'"

"Yes," said Marco, "that is right."

"'The center arch of seventy feet chord, spans the river, the water of the river principally passing under it.'"

"Yes," said Marco.

"'With a swift current,'" continued Forester.

"Yes," said Marco.

"'Twenty feet deep at low water,'" continued Forester.

"I can't see how deep it is," said Marco; "but I don't believe it is twenty feet."

"'And on each side,'" resumed Forester, "'an arch of fifty feet chord.'"

"Yes," said Marco; "but I don't see what good the side arches do, since the river all runs through the middle arch."

"It does now," said Forester, "while the river is in its ordinary bed; but when it is raised by the rains, or the melting of the snows in the spring, perhaps it requires all three of the arches to carry the water."

"'These arches,'" continued Forester, reading again from the description on the corner of his map, "'rest on abutments and piers of solid lime-rock.'"

"What are abutments and piers ?" asked Marco.

"Abutments are the foundations built up at the ends of a bridge, in the bank; and piers are those built in the middle, in the stream. When the stream is narrow, it is only necessary to have abutments, -- one in each bank, -- and then the bridge rests upon them, without any support in the middle. But if the stream is so wide that the bridge must have some support in the middle, they build up a pier. A pier stands independently; whereas an abutment rests against the bank on one side."

"Yes," said Marco. "There are two piers and two abutments to this aqueduct."

"' And surmounted,'" said Forester, reading again from his map, "'by coping' -- "

"Coping ?" said Marco, in an inquiring tone.

"That means," replied Forester, "the course of stone laid along upon the top of the aqueduct on each side, to make the sidewalks."

"Is a coping a sidewalk, then ?" asked Marco.

"O no," replied Forester, "a coping is any course of stone laid on the top of a wall of masonry, to cover and protect it. They use the coping for a side-walk here, -- that's all."

By thus examining the work before them particularly in connection with the description, Forester and Marco were convinced that it was without doubt the aqueduct; but the direction of the current of water through it remained still a mystery. Forester proposed to Marco that they should go up the river a little way, and examine the canals and cuts which were connected with it and with the Erie canal, and see if they could understand what course the water was intended to take. And they accordingly did so. But they soon got entirely lost and confounded in a perfect maze of locks, canals, cuts, waste ways, sluices, feeders and basins. Forester became greatly perplexed. Here and there he could trace the intent and design of some detached part of the work, but he could not get any clear or connected idea of the whole. There seemed to him to be a great many more channels and locks than were necessary for the canal, and he did not know for what other purpose they could be intended. As for Marco, he gave up at once all idea of understanding such a complicated system; and he walked about with Forester, paying but little attention to his surmises and speculations.

The reason why the works were so unintelligible to Forester, was that that he did not understand some important facts in relation to them. Before the Erie canal was made, there had been a short canal cut around these falls, with locks, and waste weirs, and other appurtenances; and these all remained, some full and some empty. Some parts of this old canal had been converted to a useful purpose in the construction of the Erie canal, and some parts had been abandoned. Then the Erie canal had been enlarged at this place, recently, and a new feeder provided; and there were mills and other machinery which required a supply of water and appropriate channels to convey it. All these things made the hydraulic works in the village of Little Falls very complicated. It would have required close study for a week for Forester and Marco to have understood them perfectly.

After rambling about for an hour or two, they returned to the hotel. Forester had enjoyed the romantic scenery of the place, and had been much interested in what he had been able to understand of the construction of the works, and the operation of the water. Marco had been somewhat interested too, though, on the whole, his attention had been more strongly attracted by the house painted in squares like a chequer-board, than by the cuts and canals. There was another thing also which pleased him exceedingly. It was the name which he saw painted upon the stern of a sort of scow which was floating in the basin. The name was Skipjack. Marco declared that if he ever had another boat or vessel, of any sort or size, he would name her Skipjack.

http://www.eriecanal.org/texts/Abbott/chap08.html