It was nearly nine o'clock when Forester and Marco reached the hotel. They remained there till half-past ten, waiting for the night train which was coming down from Utica. The hotel was quiet and solitary, though preparations were made to receive a large company of guests when the train should arrive. The long table in the hall was covered with refreshments as it had been in the morning; and the waiters walked to and fro in expectation of the arrival of the company.

At length the sound of the engine was heard, and a few minutes afterward the great train, borne on its twenty or thirty heavy iron wheels, came rolling on, in front of the hotel. The passengers came out and thronged into the house, renewing the scene of noise and confusion which Forester and Marco had witnessed in the morning.

While this confusion was at its height, our two travelers took their seats in one of the cars.

There was nobody in it. It was marked over the door " WAY PASSENGERS." Marco expected that somebody would come to get in before the train should start; but no one appeared. When the signal bell rang, the conductor came and shut the door, and the train began to move, leaving Forester and Marco a whole car to themselves.

There were two seats in the car, a front and a back seat. They each took one and laid themselves down. In a few minutes they were both asleep, and though Forester awoke, at intervals, when the train stopped at the various villages on the way, Marco slept soundly through the whole, being entirely insensible to every thing that passed, until Forester aroused him and told him that they had arrived at Schenectady, and that it was morning.

A few days after this, our travelers came to Troy. If the reader will look upon the map, he will find that Troy is on the North river, a few miles above Albany. Troy, as well as Albany, is a considerable city; and it transacts a great deal of business by means of the canal. For it will be seen, by looking upon the map, that the Mohawk river empties into the Hudson, but a short distance above Troy; and as the Erie canal follows the valley of the Mohawk down to the Hudson, the canal itself comes out to the banks of the Hudson nearly opposite to Troy.

It is true that the canal does not terminate here. By looking again upon the map, the reader will see that when the canal reaches the banks of the Hudson, it turns and follows the river down to Albany, where it finally terminates in a great basin, which opens upon the river.

There is, however, a communication between the canal and the river at Troy. So that the boats, after they come through the canal, can come out into the river at Troy; or they can continue in the canal until they get down to Albany, and then come out into the river through the great basin there.

Albany is upon the West side of the river which is the same side with the canal. But Troy is upon the East side. Therefore, if a canal-boat is going to Albany, it is not obliged to cross the river; but if it is to stop at Troy, it comes out of the canal into the river on the side opposite to Troy, and then they have to push the boat across the river with poles; for there can not well be a towpath made over a river so that horses can go across. There is a ferry, however, at the place where the boats cross, by which men can go over at any time; and a small town has grown up on the west side of the river where the canal comes down. This town is called West Troy.

Marco and Forester knew something of this, when they stopped at the hotel in Troy. That is, they knew that the canal passed along on the west bank of the Hudson opposite to Troy, and that there was a communication there between the canal and the river; but they did not know precisely where this communication was, or which way they were to go to find it.

"We must get across the river at any rate, for the first thing," said Forester. "We will go down to the shore somewhere, and look up and down and see if we can see a bridge."

There was a row of four-storied brick stores on each side of the street which they were walking in, which prevented their seeing the river. They, however, soon found a way to go down to a landing where they could look up and down the stream. There was no bridge to be seen down the river, toward Albany; but they saw one about a quarter of a mile above them, -- very long. It was covered, and it looked very beautifully, as Marco thought, extending in a perfectly straight line for a great distance over the water.

Forester and Marco then left the landing and walked up the river in the direction of the bridge. When they came to enter it they were astonished at its length. It was divided into two parts; one half was for the railroad track, and the other half for common carriages. By the side of the railroad track was a sidewalk for foot passengers.

When they had reached the end of the bridge, they came out into an open country, with several roads before them, and they were at first a little uncertain which way to go. They observed, however, the appearance of a town in a certain direction down the river, and they concluded to go that way. They had not proceeded far, before they found themselves on the bank of the canal. But it looked very different here from what it had done at Schenectady. It was a great deal wider, and the banks, instead of being covered with grass and the foliage of trees, were bare and gravelly. This was because they had lately been enlarging the canal at this place, to make more room for the boats to pass and repass.

Forester and Marco walked along upon the tow-path until they came to the town of West Troy. Here they found two or three large and handsome bridges leading across the canal. Here, too, was a side cut leading from the canal into the river.

"Now," said Forester, "we can see how they get the boats in and out between the river and the canal."

There was a small basin just below a bridge, on the side of the canal toward the river; and at the end of this basin there was a lock which led toward the river. Below this lock was a short canal, which led to another lock, and this second lock opened out directly upon the waters of the river. There was a boat just coming into the lower lock.

"See," said Forester, "there is a boat coming from the river into the canal; let us go and see them lock it up."

So Forester and Marco followed the side canal till they came to the second lock. They saw the boat come up through this lock, and thence to the second lock, where it was raised again. At this second lock it was raised to the level of the basin. The men then opened the gates and fastened the horses to the hoat. The driver mounted one of them, and drove under the bridge; and thus the boat was drawn along through the basin into the canal. Thus Marco and Forester saw a canal-boat locked up from the river into the canal at Troy.

"I wonder what the canal-boats go down into the river for ?" asked Marco.

There was a man standing near the gates of the lock when Marco asked this question. He seemed to have the charge of the lock, for he had opened and shut the gates when the boat went through. When he overheard what Marco said, he replied,

"Some of them go over to Troy to unload, and to take in a fresh cargo for the west; and some of them go down the river to New York. They are towed down by steamboats."

"Ah !" said Forester; "I did not know that the canal-boats went down to New York. I thought that all the merchandise came up in sloops."

"That used to be the way," said the man "but slooping is pretty much done with. They take the freight up and down by canal-boats and by tow-boats."

While this man had been speaking, Forester had observed a lock connected with the basin, which had a roof over it. It was by the side of the lock which led to the river. There was also a building at the side of it which had one or two public offices in it. Forester observed, also, some singular machinery over this lock, under the roof. He asked the man what it was for.

"That is the weigh lock," replied the man, "where they weigh all the boats."

"Weigh them !" asked Marco; "how do they weigh them ?"

"They float the boat into the lock," replied the man, "and then they shut the gates behind it, and draw off the water. This lets the boat settle down upon a frame, where it rests poised, so that they can weigh it."

So the man very civilly conducted Marco and Forester along to a door which opened into a small room in the middle of the building that stood by the side of the lock; and there they saw a large quantity of weights. They saw some apparatus there too which was apparently connected with the machinery for suspending the boat.

"But that method weighs boat and cargo all together," said Forester. "How do they know what part of the whole weight is the cargo ?"

"Oh, the weigh-master has the weights of all the boats in the canal on his register. They first weigh the boats when they are empty, and put the weight down upon the register, which is kept in the office. So they can deduct that, whenever the boat and cargo are weighed together."

"I should like to see them weigh a boat," said Marco.

"So should I," said Forester.

"I expect there will be one along pretty soon," said the man; "they are coming all the time."

So the man began to look around up and down the canal; but although there were a great many boats in sight, there seemed to be none coming just then to be weighed.

Forester then thanked the man for the information which he had given them, and then they concluded to go up upon a bridge which crossed the canal just above the basin, and look at the boats as they passed along.

This bridge had a covered way for carriages in the center, and two sidewalks outside of the covered way. The roof extended over the sidewalks, but there was no wall on the outer side of them; so that, standing upon one of these sidewalks, a passenger had a fine view of the canal. From one of the sidewalks one could look up the canal, and from the other down the canal, toward Albany.

There were a great many boats in sight from either of these sidewalks. Some were passing to and fro, under the bridge. Others were stationary, fastened to posts set in the bank of the canal, for the canal was so wide that there was room for a tier of boats to lie along the side of it, and yet allow room for the other boats to pass. There was one boat in the basin, discharging a cargo of flour. There were several long rows of barrels lying upon the bank, and they were hoisting out more. They had a sort of mast raised with ropes to brace it, and there was a tackle attached to the top of it. With this tackle they hoisted the flour out of the hold of the boat.

Marco stood for some time watching the operation of this tackle. Forester told him that the rope which the men took hold of to pull by, was called the fall. There were two men pulling at the fall, and they seemed to raise the barrels of flour very easily. When the barrel which they were raising was brought up out of the hold, the men would pull it over to the pier and roll it away.

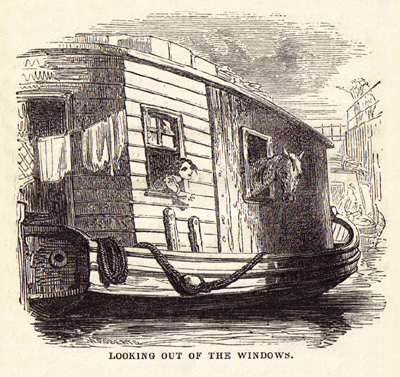

Some of the boats had women and children on board. One had a horse looking out of a window at one end of it, and a baby looking out of another window close by. Another boat, which also attracted Marco's attention, was a large flat-bottomed sort of scow, shaped like the Skipjaok.

There were loose planks, black and decayed, forming a floor at the bottom. Marco said it looked like a barn afloat. It came gliding under the bridge, and when the stern came into view, Marco saw that there was a small building erected in it, in a very coarse manner. The building looked like a little shed. There was a door in the end of this little shanty, and as the boat passed farther on, Marco saw a woman in it setting the table for tea.

Marco and Forester amused themselves for half an hour observing the various boats, and witnessing the little incidents which were constantly occurring. Then they came down to the shore of the river, where they found a boat, and a man to row them over the ferry. The river was full of fleets of canal-boats, which had been here let out into the Hudson.

-- END --

http://www.eriecanal.org/texts/Abbott/chap12.html