HISTORY OF THE CANAL SYSTEM

OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK

TOGETHER WITH BRIEF HISTORIES OF THE CANALS

OF THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA

VOLUME I

BY NOBLE E. WHITFORD

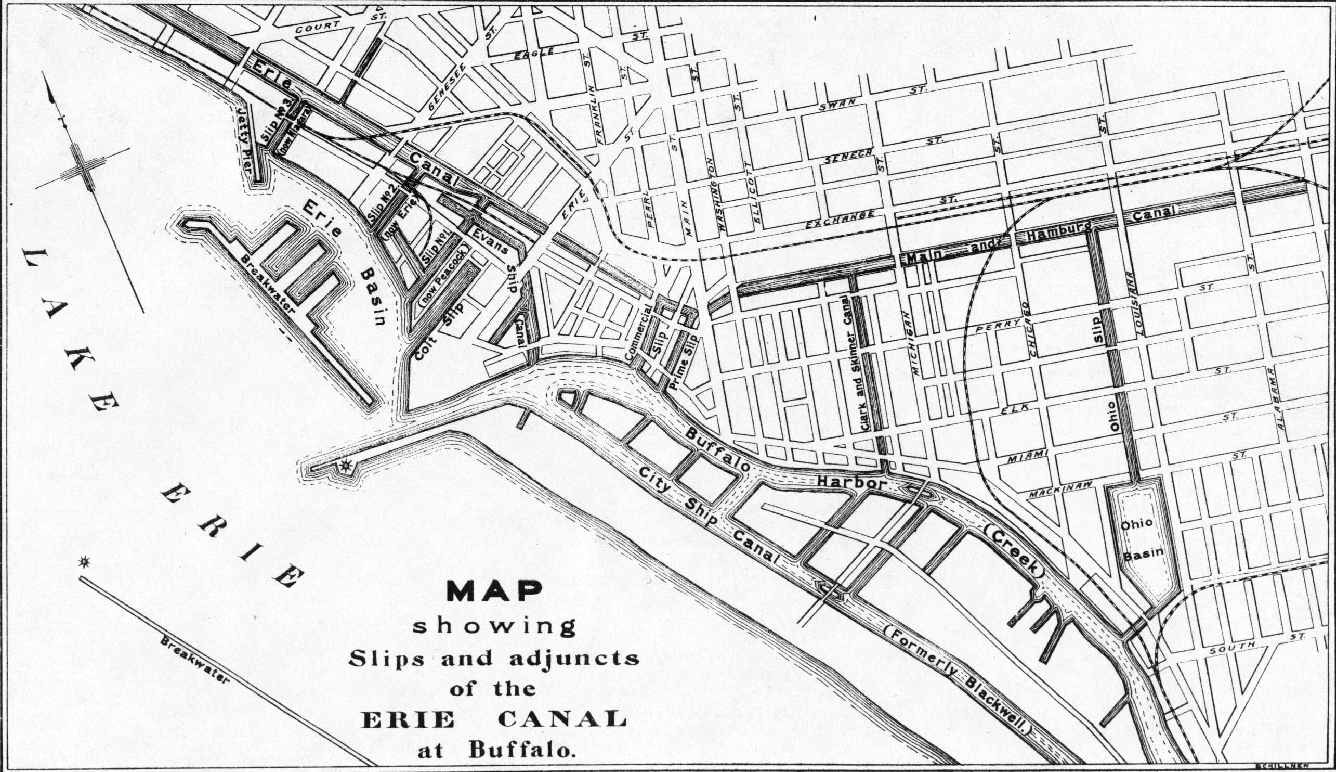

Historical accounts of the building, use and present condition of the Main and Hamburg and the Clark and Skinner canals, the Ohio slip and basin, the Prime, Commercial and Coit slips, the Evans ship canal, the Erie basin with its slips Nos. 1, 2 and 3 (now called Peacock, Erie and Niagara slips, respectively), and the City ship (formerly Blackwell) canal.

The need of a commodious harbor at the western terminus of the Erie canal was appreciated as soon as the canal itself was definitely located. In their report of February 17, 1817, before the construction of the Erie canal was authorized, the canal commissioners said: "It would be expedient to connect the west end of the great canal with the waters of Lake Erie, through the mouth of Buffalo creek.... It is important to have, at that end, a safe harbor, capable, without much expense, of sufficient enlargement for the accommodation of all boats and vessels, that a very extensive trade may hereafter require to enter and exchange their lading there." 1 In 1818 a law (chapter 120) was enacted ordering a survey and plan for a harbor at Buffalo creek, but its provisions do not seem to have been carried out. In 1819 another law (chapter 104) was passed, which empowered certain individuals to borrow twelve thousand dollars from the State to construct this harbor. By this law the commissioners were directed to have a survey made, which was done, with the result that the project was shown to be practicable, but, as the contest was then waging between Buffalo and Black Rock for the privilege of possessing the terminus of the canal, nothing more was done. In 1822, when this controversy was at its height, another act (chapter 251) offered to aid this company in building the harbor, and also promised a like assistance to the citizens of Black Rock in constructing a harbor at their village.

Eventually, there was opened in Buffalo a series of public and private slips or canals, which for many years formed important adjuncts to the main waterway and which in recent years have attracted considerable notice because of their stagnant and polluted waters. Soon after the completion of the Erie canal, it became clearly apparent that increased facilities were required to accommodate the transshipment of property between the canal and lake navigation and to provide stations or harbors at the City of Buffalo where vessels might remain when not in transit. The business of the canal soon reached such proportions that the great number of vessels engaged in traffic frequently congested the waterways terminating at Buffalo, causing vexatious delays and consequent pecuniary loss to boatmen and merchants. The first effort to eliminate this difficulty was made at individual expense. We find a record of the contract for one canal being let as early as 1831. By 1833 the common council of Buffalo had taken steps to increase terminal facilities, for the city records show that an estimate for the Main and Hamburg canal had been prepared in that year, that in 1835 land had been acquired and that a contract had been let in 1836. Four years later the State undertook the completion of one canal, which the city had begun, and subsequently of others, so that eventually, by private, municipal and State enterprise, there was built an important system of short street canals or slips, connecting the Erie canal with Buffalo creek and Lake Erie. These canals were the Main and Hamburg and the Clark and Skinner canals, the Ohio slip and basin, the Prime, Commercial and Coit slips, the Evans ship canal, the Erie basin, slips Nos. 1, 2 and 3, the City ship canal and several smaller branches of these main channels, which have not been dignified with a name. Of these the largest was the Main and Hamburg, being about one mile in length, extending from Hamburg street in a westerly direction to Main street, where it formed a junction with and became virtually an extension of the Erie canal. From Hamburg street it extended to the Hydraulic canal. As designed, it was one hundred feet wide and was to be excavated seven feet. The Clark and Skinner canal connected the Main and Hamburg with Buffalo creek and was 0.33 mile in length. Ohio slip joined the Main and Hamburg with the commodious Ohio basin, forming its southern terminus, which was connected with Buffalo creek by a short outlet. The slip was about one-half mile and the basin about one-fifth of a mile long. Prime and Commercial slips connected the Erie canal with Buffalo creek and were each about one-eighth of a mile long. Evans slip joins Buffalo creek with Slip No. 1, which, connects the Erie canal with the Erie basin, as do slips Nos. 2 and 3, the latter three slips being, respectively, 0.19, 0.11 and 0.09 mile in length. Coit slip is a cul de sac, running easterly from Erie basin. The City ship canal extends southeasterly from the mouth of Buffalo creek between the creek and the lake shore.

As previously stated, the City of Buffalo had begun operations on the Main and Hamburg canal, but the question having arisen as to the city’s authority to undertake such work, application was made to the legislature of 1838, which enacted chapter 116, authorizing the common council "to assess upon the real estate in said city to be benefited thereby the expenses of constructing a canal laid out by them from Main and Hamburg street and hence to the Hydraulic canal in said city."

In designing the construction of these various canals, it was expected that sooner or later their control if not their construction would be assumed by the State. Before much had been accomplished by the city, the attention of the Legislature was called to the project by petition and otherwise, and on April 19, 1839, that body adopted a concurrent resolution directing the canal commissioners to cause surveys and estimates to be made and to report on the advisability of the State’s assumption and completion of the Main and Hamburg canal. As a result of the survey, the commissioners reported to the Legislature at its next session in favor of granting the prayer of the petitioners. The Legislature of that year acted promptly and, by the provisions of chapter 307, authorized the canal board to complete the construction of the Main and Hamburg canal and to pay to the city of Buffalo all disbursements on account thereof, provided the common council should deliver to the State releases of the premises occupied by the canal. In accordance with the provisions of this act the sum of $12,000 was paid to the City of Buffalo, this being the amount thus far disbursed by the city in the construction of the canal. In 1841 the city deeded the lands to the State, and in 1843 the canal board ordered the construction of the Main and Hamburg canal as far as the Clark and Skinner canal, about one-third of the distance, the Clark and Skinner also having been adopted and completed by the board as an extraordinary repair in that year.

Nothing further toward completing the construction of the Main and Hamburg canal appears to have been accomplished for several years. On September 27, 1847, the canal board, responding to a request of the Assembly, rendered a report in relation to divers petitions, addressed to the Legislature by citizens and the common council of the City of Buffalo, and praying for certain improvements to the Erie canal and its adjuncts, existing and proposed. It appears from this report, 2 that seven members of the canal board, upon the invitation of the municipal authorities, visited the City of Buffalo and examined the plans and inspected the localities where these improvements were designed to be made. As a result the commissioners were unanimously agreed that these works were necessary and that adequate appropriations should be made by the State. The improvements indicated by the commissioners were: first, the immediate completion of the Main and Hamburg canal; second, the construction of the Ohio slip and basin, the basin to cover an area of ten acres and to be sufficiently deep to accommodate lake vessels; third, the connection of the Erie canal and Buffalo creek near its mouth by a ship canal, one-half mile long, three hundred feet wide and of sufficient depth to accommodate lake vessels. This connection was to be made by slips Nos. 1,2 and 3, running from the Erie canal to the ship canal, or Erie basin, as it was called thereafter.

In June, 1848, the construction of the Main and Hamburg canal was put under contract, to be completed in August, 1849. The work progressed favorably and in all probability would have been completed according to contract but for the advent of an epidemic of cholera in July, 1849. The board of health of Buffalo, deeming the existence of the freshly opened canal ditch a menace to public health and likely to increase the virulence of the plague, ordered further operations suspended and the trench to be flooded. On November 2, following, the work was relet, to be finished in June, 1850. By the close of 1849 the canal had been excavated as far as Michigan street, about one-third of the distance. It was finished in 1851 but too late to be of service that year, being filled and brought into use at the opening of the season of navigation in the spring of 1852.

The Clark and Skinner canal was commenced by individual effort and subsequently adopted by the State. On April 18, 1843, the canal board directed the canal commissioner of the western division to complete and improve the Clark and Skinner slip, provided the common council of the city of Buffalo should give releases covering the premises occupied by the canal. The commissioners proceeded with the excavations, but neglected to procure the precedent releases. From that time forward the State continued in possession of the Clark and Skinner canal, operating it and improving it occasionally.

In 1862 the canal board received a petition signed by many prominent business firms and citizens of Buffalo, calling attention to the fact that the Clark and Skinner canal had become nearly useless by reason of the falling in of the banks and the deposits in the bottom. The petition, referring to the importance and usefulness of the canal, prayed that the channel might be dredged and docked with stone as soon as possible. This petition was referred to the three canal commissioners, who reported, saying: "That, on investigation, they find said canal extends from the Main and Hamburgh canal to Big Buffalo creek, and that it is the only canal or slip connecting with said creek between Commercial and Ohio Basin slips; that it is a very important channel, and should be placed in serviceable condition.

"They find that said canal was constructed in the year 1843, by the city of Buffalo; that it is 43 feet in width, and that no record of its transfer to the State can be found; that a street has been laid out on the westerly side of said canal 40 feet in width, and that a large part of said street has slid into the canal.

"That the State has constructed several bridges across said canal, and that they are built about 55 feet in length, and that to make the canal a useful and important thoroughfare, it should be at least 58 feet in width; that to accomplish this purpose, this committee have procured a conveyance from the city of Buffalo to the State of New York, of the said Clark and Skinner canal, and releases to the State from all holders of real estate bordering on said street, of so much of said street as the State may see fit to appropriate.

"The committee, therefore, recommend the adoption of the allowing resolution:

"Resolved, That the Canal Board for the State of New York do hereby accept of the grant from the city of Buffalo, conveying the Clark and Skinner canal to the State; that they accept of the releases of the rights and interests of the property holders on Liberty street to said street.

"That this Board, in pursuance of such grant and releases, do hereby accept the said Clark and Skinner canal, in the city of Buffalo, and so much of said Liberty street as may be necessary to make such canal fifty-eight feet in width, in accordance with the map attached hereto." 3

At a meeting of the canal board held shortly thereafter, on December 11, 1862, the Attorney-General made an adverse verbal report against this resolution, on the ground that the board had not jurisdiction or power to act upon the subject. On the following day the canal board again met and resolved that the whole matter be laid before the Legislature early in the coming session. The Legislature gave the subject prompt attention and on March 23, 1863, enacted chapter 40, authorizing the canal board to accept conveyance to the State of the Clark and Skinner canal and directing the common council of the City of Buffalo to convey the same.

The Erie and Ohio basins, with their connecting slips, were provided for by chapter 445, Laws of 1847, which made appropriation for their construction. The following year chapter 213 made an additional appropriation for the same purpose. The canal board having determined upon the utility of the proposed works and the necessary appropriations having been made, the canal commissioners took immediate measures to secure the consummation of the project. A deed was executed by the City of Buffalo, conveying to the State the lands necessary for the construction of the basins. The Ohio basin and slip were put under contract July 14, 1848, and the Erie basin and slips. August 14, 1848. The former basin, when completed, was to comprise an area of ten acres, and the latter, eighteen acres. Work was energetically prosecuted and up to January 31, 1849, the sum of $6,510 had been expended in the construction of the Ohio basin and $8,296 on the Erie basin.

After the contracts had been made and the work of construction entered upon, the canal board was appraised of the fact that the land conveyed to the State by the City of Buffalo for these basins had not been paid for in full. The matter having been submitted to the Attorney-General, that official verbally reported to the board that the title to the lands designated for the sites of the basins would not be vested in the State until the owners thereof had been fully compensated. Whereupon the canal board, being convinced that the owners had not been so compensated, resolved: "That the Canal Commissioners be advised by this Board not to expend any further moneys upon or towards the construction of said basins respectively, until said lands for the respective sites thereof, shall have been actually paid for by said city; and that they suspend all further operations on said basins respectively, unless such lands be paid for by said city within thirty days after a copy of this resolution shall have been forwarded by mail to the mayor or common council of said city, or such further time as the Commissioners may deem reasonable. 4

As the canal board was of the opinion that some alterations should be made in the construction of the Erie basin, the Legislature by the enactment of chapter 234, Laws of 1849, conferred the necessary authority, directing the board to make such change or alteration in the location or dimensions of a portion of the basin as in their opinion would best subserve the interests of the State, upon condition that the common council of Buffalo should agree to the same and convey to the State all lands necessary for the purpose. The law also gave the canal board power to cancel the contract, after settling with the contractors for work already done.

The Erie basin and the three connecting slips were again advertised on a plan approved by the canal board, and were put under contract for the second time in February, 1850, and work was begun in the spring of that year. The change of location materially increased the area without adding to the cost of constructing the basin, and also secured the additional advantage of allowing the basin to be increased in the future to any desirable extent commensurate with the requirements of commerce. In 1850 a breakwater, designed for the protection of the basin, was built to the surface of the water for a distance of eighteen hundred feet, leaving about three hundred feet to be constructed. Some eight hundred cubic yards of cement masonry were laid during that year, the wall being six feet wide and about six feet high, but in the spring of 1851 several hundred yards of this masonry were broken to pieces and swept from their foundation by the severe storms of the lake. The canal board subsequently changed the plan of construction by increasing the dimensions of the sea-wall and by providing for a continuous crib outside of the piles so as to break the force of the waves before they could reach the wall. In the summer of 1851, when the channel was partially protected by the breakwater, the dredging of the basin was commenced. During the same year one slip was excavated, cribbed and brought into use and the completion of the two others promised for the following summer.

Speaking of the Erie basin and slips in their report for 1856, the canal commissioners said: "Several changes in the plan of construction have been made by the Canal Board, largely increasing the cost of the work; during the past year it has been prosecuted principally upon the change of plan adopted in 1855, with the exception of the channel excavation, and is now so far advanced that it may be fully completed by the spring of 1858." 5

From the annual report of the canal commissioners for 1857 we learn that the contract for the construction of the Erie basin and slips, not having been prosecuted as required, was declared abandoned December 29, 1857. The work was soon advertised to be relet. In this report the commissioners said further: "The expenditures upon this work the past season have been confined mainly to the breakwater, which was extended to the length designed, the masonry built and partially protected in the rear with piles and loose stone, but not to the extent required by the contract, and during the gale on the first of November last [1857], a portion of it was broken down, which leaves the balance of the wall between that and the northern termination, a distance of about 150 feet, much exposed and liable to be carried away before the season will admit of its being secured. The work remaining to be done so far as contemplated under the present plan, consists of rebuilding such portions of the masonry as may be found necessary, finishing the outside protection to the break-water, completing the channel excavation, a large portion of which has already been done, removing the deposits from slip No. 3, and building a pier to protect the entrance to said slip" 6

In 1861, the canal commissioners in their annual report for the preceding year said of the Erie basin and slips, that under the contract of February, 1850, up to 1857, when the work was abandoned, "work to the amount of $295,608 was done." Continuing, they said: "On the 4th of March, 1858, the work was again put under contract ... and has progressed to the present time, except when suspended for want of funds. Under this last contract, work, by the estimates, to the amount of $63,455, has been done. Owing to the limited amount of funds that could be applied to this work, the expenditures, under the last contract, have been confined to the breakwater.... It is estimated that $4,180 more will complete the breakwater, which will make the whole expenditure upon the work, $363,248. There will then remain to be done, to complete the whole work according to the original plan, the finishing of the ‘Jetty pier,’ ... and the reconstruction and finishing of the docking around slip No. 3 and its vicinity. To finish pier and docking will cost, according to the estimates, $18,411.

"Though there may be differences of opinion as to the original policy of embarking on this extensive work, involving, as it has, so large an outlay, it is believed there can be no difference as to the policy of now completing it substantially in accordance with the original plan. It is an important work, furnishing a harbor for lake and canal craft, and a convenient and important connection between lake and canal commerce.

"The ‘Jetty pier,’ at the lower side of the basin, is designed, and is important, to protect the basin and slip No. 3, and the canal (if the slip is kept open), from the heavy swells and accumulation of sand from the lake and river. It is believed that, unless the pier is completed, the basin will, in a few years, be very much obstructed by sand and other deposits. Piles have been driven for the pier, and a small part of the crib work has been done." 7

In the year following the commissioners reported: "But little has been done within the present year. Since the last report the canal board has ordered the plan of construction of the jetty pier to be changed by substituting stone masonry for timber, the estimated cost of which is $16,570." 8

The jetty pier in the Erie basin was, with the exception of coping stones, completed in September, 1862.

It was the intention of the authorities, when the construction of the Erie basin was decided upon, to excavate the earth therefrom in a channel three hundred feet wide to the depth of twelve feet for the purpose of permitting vessels and canal-boats to exchange their cargoes in the basin. A contract was entered into for this purpose, but before it could be completed, the work was suspended by the operation of chapter 169, Laws of 1862, which prohibited further expenditure on this as well as on most of the canals of the state.

The canal commissioners, speaking of this necessary improvement in 1864, say in their annual report: "A large portion of the land used in the basin was donated by the city of Buffalo with the understanding that important improvements were to be made. The large amount of harbor room now occupied by canal boats to the detriment of vessels renders the pending improvement now of great importance. No dredging has over been done by the State and to make a channel as contemplated and contracted for under the enlargement would require the removal of 60,000 yards of material at an estimated cost of $18,000." 9

At a meeting of the common council of Buffalo, held February 28, 1853, the names of slips Nos. 1, 2 and 3 were changed by resolution to Peacock, Erie and Niagara slips, respectively.

Not much difficulty appears to have been encountered in constructing the Ohio slip and basin. The slip was completed in 1850, and the basin in 1851.

One of the most important and useful of the many slips or street canals at Buffalo is Evans slip. It was constructed entirely by the Evans estate. The contract for its construction was advertised and let in 1831; work was commenced the year following and the canal entirely completed two years thereafter, or during the year 1834. For many years the slip was known as the Ship canal, but as this designation was provocative of confusion, owing to its resemblance to the city ship canal, it eventually led to the adoption of the following resolution by the common council in 1853, when the names of some other slips were also changed:

"Resolved, That it be and is hereby ordered and determined that the ship canal lying west of Norton street and heretofore known as the Ship canal be hereafter known and designated as Evans Ship Canal." 10

Probably Commercial slip was constructed by the State at the time of building the Erie, in forming the connecting link between the canal and Buffalo harbor, or Buffalo creek, as it was called in the early days. It is shown inclosed within the "blue line" and designated simply as a "basin" on the first official map of the State canals, the surveys for which were begun soon after the completion of the Erie, this portion, however, not being surveyed until the autumn of 1833. The records show that the State has done some work in the slip from time to time, chiefly in dredging the channel.

Prime slip -- a canal forty feet wide -- was opened by private enterprise at an early date. It is shown on the map just mentioned with the name "Thompson’s cut." It remained under private control during its entire existence, as was evidenced when the city undertook to fill in the channel, as we shall see presently.

Coit slip was built at private expense and has never been acquired by the State or city.

The City ship canal, originally known and officially designated as the E. R. Blackwell canal, was laid out by the City of Buffalo on the southerly side of Buffalo creek. Commencing at a point near the old lighthouse, it extended to the south channel and was connected with the Buffalo creek by a number of short slips or street canals. Being two hundred feet wide and twelve feet deep, it proved to be a very important acquisition to the Erie canal.

The City ship canal was projected as early as 1836, but no definite action presaging actual construction was taken until 1847, when initiatory proceedings to acquire title to the necessary land by condemnatory measures were instituted. Commissioners having been duly appointed to appraise the damages for land appropriated, and their report of February 6, 1849, having been confirmed without delay, the common council of Buffalo directed the city surveyor and the street commissioner to make surveys, estimates, etc., for the proposed canal. These officials reported to the council in March of the same year, estimating the probable cost at $61,000. As is usual in cases of proposed public improvements, some remonstrance was expressed in the press and otherwise, but despite this opposition the contract was promptly awarded to E. R. Blackwell and the work of construction actively prosecuted. Early in 1850 it became apparent that the estimate of cost had been entirely too low. The construction of the southern half of the canal alone had necessitated an outlay of about $73,000. The existing contract with Mr. Blackwell was canceled and a new one, based on revised estimates, was made with the same contractor, the canal being completed and brought into use during the same year -- 1850.

In 1853, when the names of some of the other slip were changed, the name originally conferred upon this channel -- E. R. Blackwell canal -- was also changed by resolution of the council and thereafter it became known by its present title -- City ship canal.

In 1873 by direction of the municipal authorities, it was improved, being made one hundred and forty feet wide and fifteen feet deep. In 1883 the Buffalo Creek Railway Company applied for and obtained permission to extend the canal in a southerly direction into its own lands. This portion is now occupied by the Lehigh Valley Railroad coal docks.

For years the slips and basins amply and well subserved the purposes for which they were constructed, but, despite their unquestioned value, some of them were destined to become a source of trouble and annoyance to the residents in their neighborhood. These slips, together with the Erie canal, extended along the greater part of Buffalo’s lake front, and thus became the receptacles for much of the sewage from the city.

The Main and Hamburg slip, the most important of the street canals, by reason of its position became the most troublesome. Being devoid of current, it was declared a nuisance as early as 1855. From that time frequent and costly attempts were made to create a current, and thousands of dollars were expended by the city in operating pumps, wheels and curious mechanical devices to produce this result, but without success. Among the devices adopted to abate this nuisance may be mentioned the following: a ditch to Little Buffalo creek (1855), the introduction of a current of water from Big Buffalo creek (1869), the construction of a trunk sewer and the extension of the canal to Buffalo river (1870), the establishment and operation of a stationary tug in the canal (1877), the erection of a series of gates in the canal and the construction of a dam across Black Rock harbor, the boring of artesian wells and finally a return to the trunk sewer plan (1880). However, all efforts proved unavailing; the desired current was not permanently established and the nuisance successfully resisted every attempt at elimination. Finally it was seen that the channel must be filled, and in 1894 the State Constitution was so amended as to exempt this canal from the provision which prohibited the lease, sale or other disposition of the State canals.

In his report for 1896, the western division engineer gave a description of the condition of the canal at that time, together with a short account of the increasing trouble. He said:

"The State, with little or no restrictions, has allowed the city of Buffalo and its citizens to empty sewage into the Hamburg and Erie canals. The Erie canal, because of its situation and because of its constant use for navigation purposes, is not so badly polluted as the Hamburg and its slips. The Hamburg canal, situated as it is, has no current, and has not for a number of years been used for navigation, and has become nothing more than a stagnant body of water into which a large amount of Buffalo’s drainage empties.

"The Hamburg canal was built in 1846, and as early as 1855 attempts were made to abate the nuisance it then created. From that time until 1882 various plans were tried to create a current in the canal and thus cleanse it; but none were successful. In 1882 Col. G. E. Waring proposed to relieve the difficulty by constructing an intercepting sewer, running generally parallel to the Hamburg and Erie canals and emptying into the Niagara river near Ferry street.

"The sewer was built, but proved a failure, either from faulty construction or design, and the condition of the Hamburg is as bad now as it ever was. For the last few years the city has been spending $6,000 per year operating pumps and wheels to create a current. The current, however, is not apparent." 11

In view of the great importance to both city and State of abating this nuisance, the division engineer presented plans and estimates for this purpose in this same report. His proposition was to build sewers in the Main and Hamburg and the Clark and Skinner canals with an outlet at the junction of the latter with Buffalo creek, where a gate was to be placed, so that the sewer could be pumped out and cleaned. He proposed also to fill in these canals, together with that portion of the Ohio slip lying north of Elk street, estimating the whole cost at $389,000. He declared that the adoption of this plan would reclaim about twenty-three acres of land occupied by the canals and estimated to be worth over a million dollars, that the sanitary condition of 3,640 acres would be vastly improved, and that the maintenance of ten bridges would be obviated, saying that the canals thus to be abandoned were practically of no use for navigation. He suggested three methods for carrying out his plan: first, that the State should do the work and then dispose of the reclaimed land; second, that the State should give the canals to Buffalo on condition that the city should do the work; third, that the canal should be sold to the highest bidder on the same condition.

The Legislature practically adopted a course corresponding to the second suggestion. In 1898 an act (chapter 295) authorized the abandonment of the Main and Hamburg canal and its conveyance to Buffalo upon condition that the city fill in the prism, abate the nuisance and save the State harmless from all damage. In 1899 an act (chapter 578) empowered Buffalo to sell this canal, and another (chapter 579) authorized the city to raise $550,000 for the purpose of filling the channel and abating the nuisance. Another law of this year (chapter 663) provided that no corporation could take this canal by the right of eminent domain.

In his annual report in 1901, the western division engineer described the subsequent action of the city. He said:

"The State has abandoned the Hamburg canal to the City of Buffalo, which is constructing a large overflow sewer from the Hamburg sewer in same and filling-in the prism. The Ohio Basin slip and Clark and Skinner canals extend from the Hamburg canal to the Buffalo river, and the closing of the Hamburg has stopped what little current formerly existed in them. Sewage and other refuse deposited in these two slips is rapidly filling up the channels and rendering them foul. The City of Buffalo is constructing a branch from the sewer in the Hamburg canal, to empty into the Ohio Basin slip. The usefulness of these slips for navigation has probably passed, and they should either be filled in and remove the necessity of rebuilding the now obsolete bridges carrying the streets over them, or some means provided of preventing them from becoming nuisances." 12

In 1901, by chapter 651, the portion of the Ohio slip north of Elk street was abandoned and conveyed to Buffalo upon the same conditions mentioned in connection with the transfer of the Main and Hamburg canal.

When the attempt was made to transfer the Clark and Skinner canal to the city in like manner, the fact was brought to light that a clear title to the land had not been obtained at the time of its construction. By an oversight, it seems, in procuring the necessary land for the canal in 1843, the city obtained a mere easement, as no precedent power to acquire the fee had been conferred by the Legislature. This untoward circumstance led to considerable trouble and expense more than half a century later. It will be remembered that in June, 1862, the mayor and city clerk of Buffalo, having been duly authorized, executed a deed conveying this canal to the State.

On December 31, 1901, the canal board abandoned the Clark and Skinner canal. Upon being notified of this action, the mayor, common council and corporation council of Buffalo immediately took steps to acquire the canal, forwarding to their legislative delegation at Albany two proposed enactments -- one to confer the title upon the city on condition that the municipality should abate the nuisance, and the other to authorize the raising of $100,000 for this purpose. The act to raise the money was passed and became chapter 461 of the laws of 1902. The measure to cede the title to the city passed the Assembly but failed in the Senate, on the ground that the commissioners of the land office were the proper officials to dispose of the canal. Thereupon the city authorities applied to the commissioners of the land office, requesting that the title to the canal be granted to the city upon condition of Its removing the nuisance. At this time the city was made aware of the fact that a private corporation -- a cold storage company -- had also made offers for acquiring this title. A committee of officials representing the city was appointed to wait upon the commissioners, and its request was granted for a reasonable delay before final action should be taken.

Meanwhile the city was legally informed that by its right of eminent domain the New York, Lackawanna and Western Railway Company had taken steps to obtain title to the canal lying between Elk and Perry streets, the portion situated in front of its property. The commissioners appointed by the Supreme Court in these proceedings appraised the damages due to the State at $7,488.19, while to the city they awarded merely nominal damages. This award was duly confirmed by the Supreme Court at Special Term.

In 1903, by chapter 535, Buffalo was authorized to raise $100,000 for abating the nuisance and filling the prism of this canal, in the event of its acquiring the title. In the next year a successful appeal was made to the Legislature and an act (chapter 565) conferred upon the city the titles to the remaining portions of the Clark and Skinner canal and also to Liberty street -- a strip forty feet wide, adjoining the canal and extending its entire length. This act also enabled the city to build sewers in the canal and street.

Prime slip suffered the same experience with respect to its ultimate sanitary condition. As early as 1865 it was officially declared a public nuisance and ordered to be filled. In the summer of the following year a number of actions were brought against the City of Buffalo, praying that it be restrained from filling this slip. Several of these actions were brought to trial in the Superior Court in January, 1867, notably that of George G. Babcock vs. The City of Buffalo. The plaintiff was an owner of land adjoining the slip and sought to restrain the city from filling the canal and requiring it to remove the filling already placed therein. The issues in the action were submitted February 4, 1867, and resulted in a decision favorable to the interests of the city. Babcock appealed to the General Term of the Superior Court, which reversed the judgment of the court below and rendered judgment for the plaintiff, perpetually enjoining the city from filling the slip. The city carried the case to the Court of Appeals which affirmed the order of the General Term and directed the city to remove the filling from the canal in front of the plaintiff’s premises. Finally after much local legislation by the common council, ordering the reopening of the slip, the city effected compromises with the property owners.

Before describing the present condition of these various slips and canals, it may be well to briefly mention a structure which was made necessary by the polluted condition of these waters. In 1867 the western division canal commissioner said in his annual report: "It has also been suggested, by the Engineer Department, that a jetty pier be constructed, above the arm of the main pier, for the purpose of throwing out, in the Niagara river, the sewage and other debris from the city, which have been rapidly filling up Black Rock harbor." 13

This proposed pier was to be placed at the foot of York street; it was to be seven hundred feet long and was estimated to cost $7,500. The Legislature of 1868, responding to the recommendations of the commissioner, enacted chapter 715, among the items of which was one of $7,000 for the construction of a pile jetty pier at the southerly end of the Black Rock harbor. The pier was completed during the fiscal year ending September 30, 1870.

The Main and Hamburg canal has been filled throughout its entire length, and recently it was-sold by the City of Buffalo to Messrs. Lee, Higginson & Co., the Boston, Mass, capitalists, acting as agents for the Wabash Railroad Company, for the sum of $901,000. The sum realized by the city through this sale was, by resolution of the common council, created a fund to be known as the Canal Nuisance Abatement Sinking Fund. This fund is to be set apart and held for the redemption of the bonds floated in aid of the construction of sewers and the abatement of nuisances in the Main and Hamburg, Clark and Skinner and Ohio slips.

The Clark and Skinner canal is open between Perry and Scott street, about one-third of its extent, and has been filled between Perry and Ohio streets -- the remaining section. The New York Lackawanna and Western Railroad Company, owner of that portion of the canal lying between Perry and Elk streets, has erected thereon a fine, commodious freight depot. The sewer mentioned in chapter 565, Laws of 1904, is in course of construction.

The Ohio slip has been filled in as far south as Elk street and lies open beyond that point.

Prime slip as has been recorded was filled in with solid material during the late ’sixties.

Erie basin and its three connecting slips, Peacock, Erie and Niagara (formerly called slips Nos. 1, 2 and 3, respectively), are still open.

Evans ship canal, Commercial and Coit slips and the City ship canal are all similarly open to the uses which suggested and brought about their construction.

1 Laws ... in relation to the Erie and Champlain canals, etc. Vol. I., p. 198.

2. Assembly Documents, 1847, No. 205.

3. Senate Documents, 1863, No. 16, pp. 3-4.

4. Senate Documents, 1849, No. 26, p. 4.

5. Assembly Documents, 1857, No. 145, p. 150.

6. Assembly Documents, 1858, No. 20, pp. 152-153.

7. Assembly Documents, 1861, No. 57, pp. 87-88.

8. Senate Documents, 1862, No. 26.

9. Assembly Documents, 1865, No. 10.

10. Manuscript Minutes of Buffalo Common Council, p. 554.

11. Assembly Documents, 1897, No. 73, pp. 580-581.

12. Assembly Documents, 1902, No. 31, p. 309.

13. Assembly Documents, 1868, No. 9, p. 124.

http://www.eriecanal.org/Texts/Whitford/1906/Chap13.html