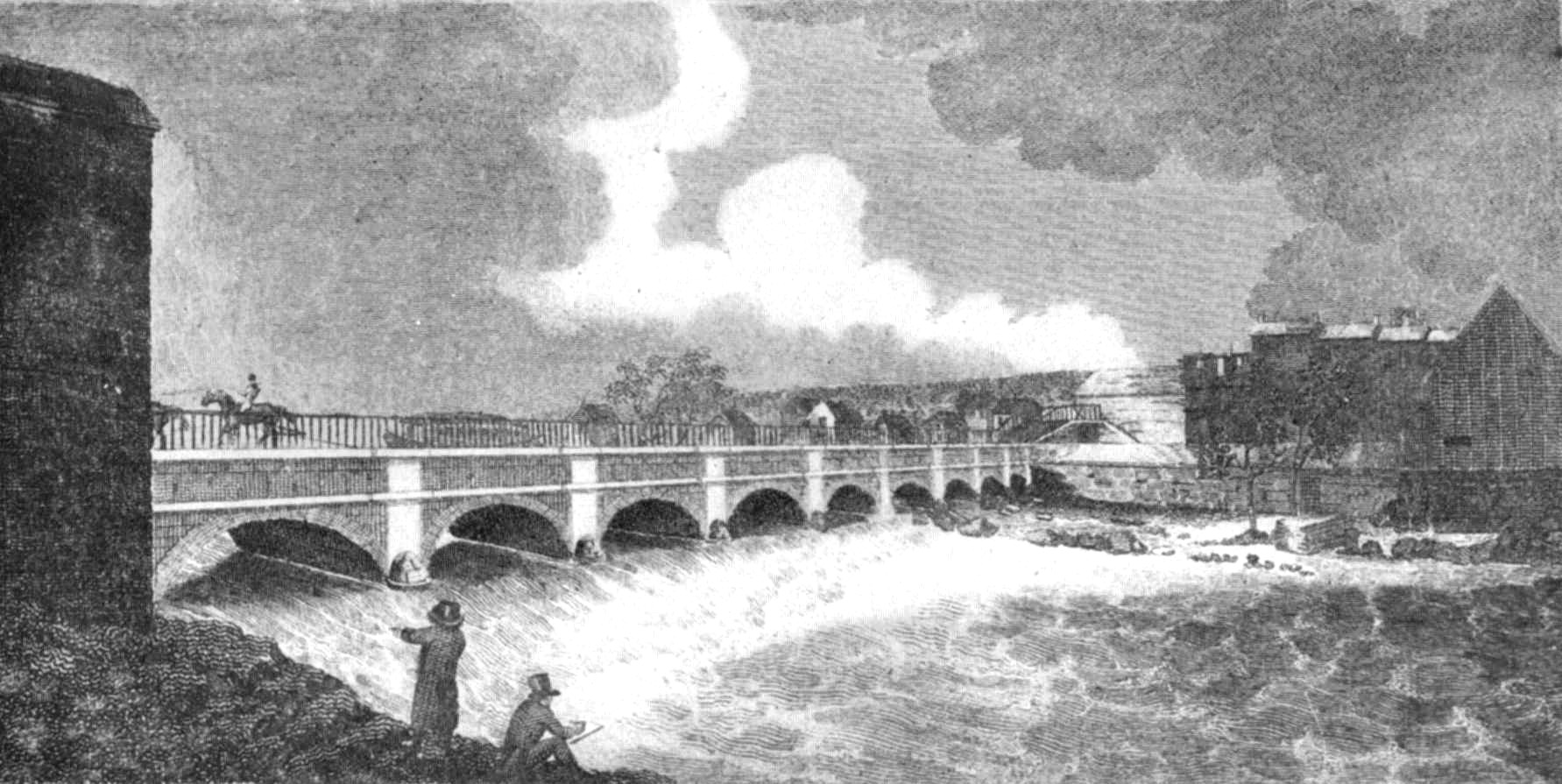

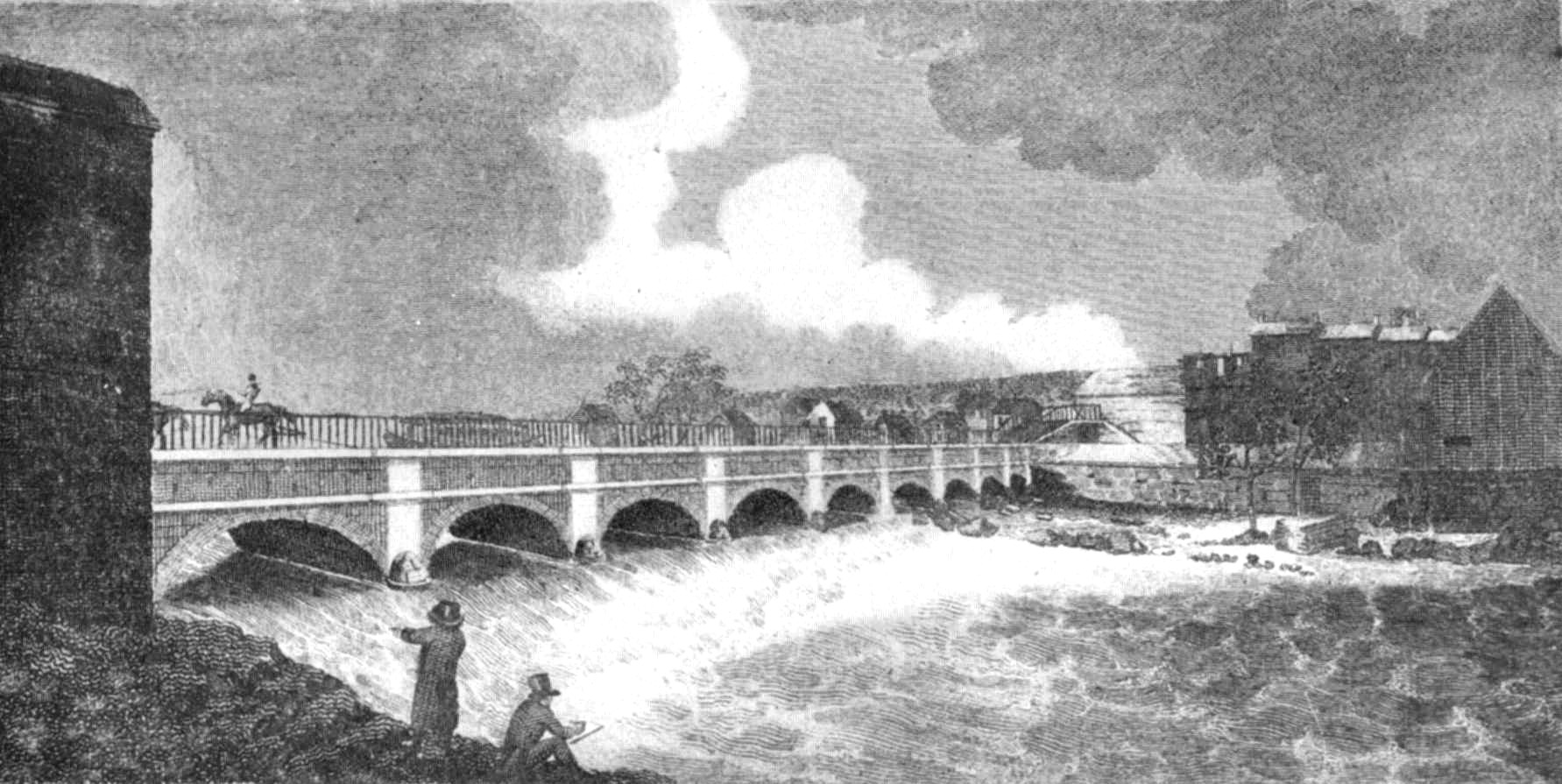

VIEW OF THE AQUEDUCT BRIDGE AT ROCHESTER.

Reproduction of an old print, published during the construction of the original Erie canal;

design was also used for decorating china.

HISTORY OF THE CANAL SYSTEM

OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK

TOGETHER WITH BRIEF HISTORIES OF THE CANALS

OF THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA

VOLUME I

BY NOBLE E. WHITFORD

From the formal opening of the original canal to the completion of the first enlargement.

The period from 1825 to 1834 was a time of development for the Erie canal, during which no radical changes were made, and the improvements undertaken were such as to add to the permanency and stability of the canal. Succeeding this period came the first enlargement of the Erie, which was not completed until 1862. After the opening of the canal in 1825, traffic had increased by leaps and bounds, and the revenue collected from tolls demonstrated the wisdom of the builders and presaged unbounded prosperity for the future. From 1826 to 1834 the aggregate tolls amounted to $8,539,377.70. Indeed, so marked was the success of the Erie that a veritable frenzy for canal-building spread over the whole country, which manifested itself in New York State in a flood of petitions to the Legislature for the opening of the water-ways, in the surveys of hundreds of miles of proposed routes. In the building of several unremunerative and -- in the light of later history -- ill-advised lateral branches and in the incorporation of more than sixty private canal companies. One act alone, the "great canal law" of 1825 (chapter 236), ordered the surveys of seventeen contemplated canals, covering a distance of over twelve hundred miles, and many other surveys were made later. Within the first decade after the completion of the Erie, six canals were built, having a length of two hundred and ten miles, and during the next four years four more, with a length of two hundred and forty miles, were authorized. These, together with the five hundred miles embraced in the original Erie and Champlain, the navigable feeders and later laterals, and the one hundred and five miles of canals built by two private companies made an aggregate of about ten hundred and sixty miles constructed in the state.

After the opening of the canal, one of the first troubles experienced came from the rapid movements of packet and light freight boats, which were having a destructive effect on the banks of the canal by driving the water along the face of the banks, washing them away, and depositing the earth in the bottom. These boats also had the right of way in passing locks -- another cause of dissatisfaction among boatmen -- so that it was attempted to reduce their number to two daily, and in the course of time to abolish them entirely, for upon investigation it was found that the revenue collected from these packets amounted to about one-twentieth of that collected from the freighters. 1 The sides of the prism were repaired by building a slope wall of stone in some places and of wood in others; the banks were also raised in places. Up to 1828 about two hundred and fifty miles of canal had been protected in this way, at a cost of about $1,600 per mile, where both banks were walled. As early as 1822 it had been found necessary to enact a law (chapter 274), to limit the speed of boats to four miles an hour.

In numerous places it was found that the locks had settled somewhat and needed to be replaced. In several instances it was considered that two locks would soon be useful, if not necessary, in facilitating the increasing business of the canal, and that the loss and inconvenience to the public by stopping navigation at these places, while repairs were in progress, would be greater than the cost of another lock. Therefore, whenever it became necessary to rebuild the structures, a lock was constructed adjoining the old one and after its opening repairs were made to the old lock without in any way interfering with navigation.

During this period the feeder from Limestone creek was completed (1826), and a feeder from the Mohawk river at Rome was constructed (1826). Stone waste-weirs were built and guard-locks were altered and improved. Nearly all the bridges were raised and repaired, and ditches were cut to receive the water leaking from the canal. In 1827 a new lift-lock at Fort Plain was finished, and the dam at the head of the Genesee river feeder was raised fourteen inches. In 1828 two new weigh-locks were built to replace the hydrostatic locks at Syracuse and Troy, and In 1829 another was completed at Utica. In the spring of 1832 a large break occurred in the canal embankment near the village of Perrinton, and being of great size, it interrupted navigation for a considerable time. To guard against a repetition of this occurrence, and to avoid the necessity of such expensive repairs in the future, several new and larger waste-weirs, together with new guard-locks, were built.

In 1833 a considerable amount of repairing was done, a large percentage of it being caused by the heavy freshets in the Mohawk river. The aqueducts across Oriskany, Butternut and Oneida creeks had to be repaired, having been built of soft and porous stone that could not withstand the climatic changes to which it was exposed. The aqueduct across Mud creek had to be partially rebuilt, and while this was being done the trunk was widened to admit the passage of two boats. It was at this time (1833) that the tolls were reduced 28 ½ per cent, going to tide-water, and 14 ¼ per cent, going from tide-water. In this year also the number of acting canal commissioners was increased from two to three.

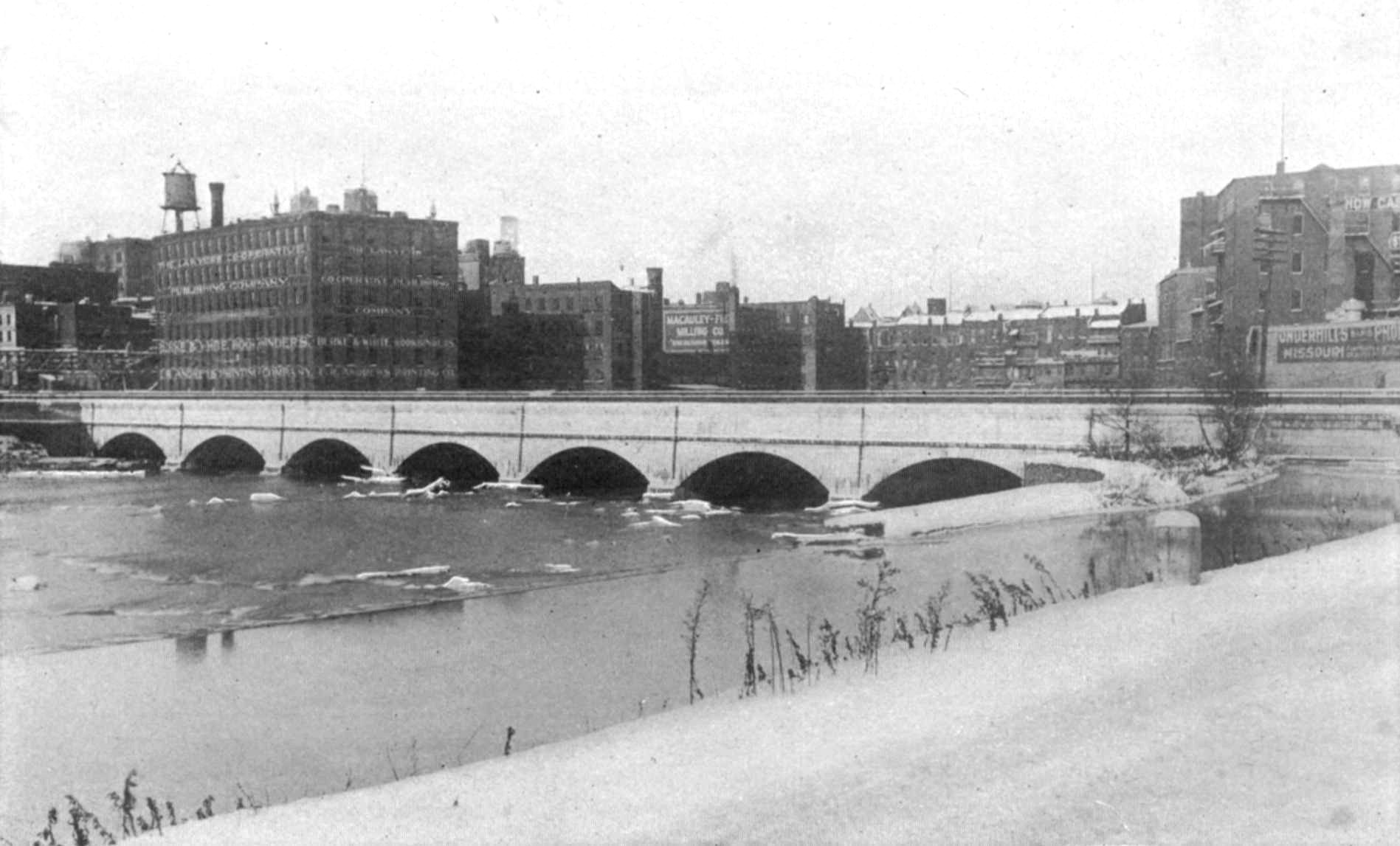

In 1834 came the first step toward an enlarged canal. The canal commissioners submitted a special report 2 to the legislature in relation to rebuilding the aqueduct at Rochester, taking an additional feeder into the Erie canal at Camillus on the Jordan level and doubling the locks upon the Erie canal east of the village of Syracuse. Traffic had increased so rapidly and the crowding of boats, especially on the eastern section, had become so great as to demand some relief. The commissioners, therefore, suggested the doubling of locks as a possible remedy. In speaking of this in 1851, State Engineer Seymour said: "As early as 1832, the project of doubling the locks on the Eastern division began to be a subject of conversation. In 1834 the Canal Commissioners made a special report to the Legislature ... the first official allusion to the necessity of enlargement." 3 However, as early as 1825 the canal commissioners had perceived the need of greater facilities and in their report to the Legislature on March 4, of that year, had suggested the propriety of doubling the locks. As the construction of double locks appeared extremely difficult at some points, they "presumed that the experience of two or three years more, [would] satisfy the public, that it [would] be proper to commence the construction of another canal parallel with the eastern section," proposing a location on the north side of the Mohawk between Utica and Schenectady.

The commissioners reported that during the season of 1833 it had been shown that the lock west of Schenectady had made more than twenty thousand lockages. They thought that with double locks the canal would be able for some time to accommodate the traffic and still continue to employ boats of the tonnage then in use. Because, from its position, boats could not so readily enter, pass through and clear from the berme lock as the towing-path lock, they thought it probable that forty thousand lockages would be found to approach the greatest number that could be made with double locks in a single season. However, they believed that, within no remote period after the locks could be doubled, the increased transportation would equal if not surpass the capacity of the locks to accommodate it. To meet this need, the commissioners thought that the locks must be extended and the canal enlarged. Accordingly, they recommended that the new locks should be built ten feet longer than the existing structures.

Governor William L. Marcy, in his annual message to the Legislature of 1834, called attention to the phenomenal increase of western settlement and its existing and future requirements for transportation, saying: "If our canals are to be what a wise management cannot fail to make them -- the principal channels for this trade -- we must calculate its extent, and make them adequate to this object." But New York State, he continued, could not be expected to enjoy the benefits of the western trade without effort, as other Atlantic states were making powerful efforts to remove the natural barriers which hindered their competition for this prize. Canal traffic was always to be increased by bettering facilities of transportation and reducing expenses. By enlarging the capacity of the Erie canal the cost of transportation would be diminished. Tolls were a large factor in this, he said, and had been carefully and judiciously modified by the canal board during the preceding year, with the result of more widely diffusing the trade throughout the West and Southwest. A substantial reduction had been made for the season of 1833, yet, notwithstanding this, the Erie and Champlain canals had received in tolls $1,464,259.98, an increase of $234,776.51 over the year before. 4

Appreciating the importance of this subject, the Legislature passed an act, 5 which authorized the commissioners to build double locks between Albany and Syracuse of such dimensions as they deemed proper. This law also directed the taking of Nine Mile creek as a feeder into the Jordan level, the reconstruction of the Rochester aqueduct and the building of sluices around locks on any State canal. As a preliminary step the commissioners employed Mr. Holmes Hutchinson to examine the sites for double locks and to furnish the proper plans and estimates for their construction, and also for the construction of such works as would be proper to adapt the canal to the use of such locks.

In rendering their report, 6 the commissioners said that, from a careful consideration of the provisions of the act, it was apparent that the Legislature designed to give to the canal and its locks sufficient capacity for whatever transportation the country might require in the future. With the existing capacity of the canal, the section west of Syracuse furnished ample accommodation, and would for some time, but on the eastern section the want of adequate facilities was acutely felt and the crowding was rapidly increasing. In studying the problem of locating double locks, the commissioners considered the subject under three heads: first, what capacity should be given to the canal and locks east of Syracuse, and in what manner it should be afforded; second, what course should be adopted to afford sufficient capacity to the short reaches between some of the locks; third, what should be the lateral distance between the double locks and what their relative location.

In reference to increasing the capacity of the canal by doubling the locks, two methods were suggested -- by simply placing two locks side by side, and by building a second towing-path in addition to the double locks. By increasing the width of the canal for the free passage of four boats, and constructing a towing-path on the berme side, each lock would then be able to perform with equal advantage and no change would be necessary in the old locks. This course, however, was subject to great and insuperable objections; no boats could lie at rest In the canal for loading, unloading or any other purpose; all wharves, basins and slips would have to be made by cuts through the towing-path and the path would consist of a succession of bridges over these cuts. Without adding to the depth of water in the canal or the length of locks, the tonnage of boats could not be increased. It was not supposed that twice the number of boats could as conveniently be passed on the canal with double locks and with one towing-path, as were formerly passed with single locks and with one towing-path. When twice the capacity of the existing canal was reached, the double locks would have attained their utmost limit, and the commissioners believed, as they had a year earlier, that forty thousand lockages per season approximated the maximum capacity of double locks with a single towing-path. They estimated that this limit would be exceeded within eight or ten years, and that within a shorter period the locks would be unable to accommodate traffic during the busiest part of the season. Accordingly, they considered that a widened and deepened channel and enlarged locks were indispensable, if such ample provision for transportation were to be made as was evidently contemplated by the Legislature.

In regard to the short levels, or pound-reaches, the commissioners considered it desirable that water drawn from or thrown into a level at any single locking should not change its water-line more than six inches. They thought that the most advantageous arrangement was to change the locations of the locks so as to make the length of each level at least three and a half boat lengths, and to make the canal wide enough at these reaches to afford the necessary water for locking without injurious change in the level. The proper lateral distance between locks was determined to be twenty-six feet. This would afford space for the regulating or feeding sluice between the lock walls and would require that the canal above and below the locks should be excavated to the width of about seventy-six feet. Believing that the provisions of the law of 1834 were inadequate to satisfy the impending needs, the canal commissioners did no more than cause surveys to be made, submitting their report to the Assembly on January 31, 1835, thus giving the Legislature a chance to reconsider its action of the preceding year.

During the whole period of the first enlargement of the Erie, the canal policy was so closely connected with the financial condition of the State that a clear appreciation of the one is needed to fully understand the other. Indeed, the financial situation in 1845, which largely induced the Constitutional Convention of 1846, was almost entirely due to the canal policy. The history of this entire period is, in fact, as largely one of finance as of engineering or of constructive operations. It is accordingly proper, before considering further the progress of the events which led to the work of construction, to review briefly the situation.

In his annual message of 1833, Governor Marcy gave a concise summary of the State’s financial history for the past two decades. He said: "The general fund is almost exhausted, by the liberal contributions it has yielded to all the other funds, by the payment of the State debts, and by furnishing, unaided for the last five years, all the means for the ordinary and extraordinary expenses of the government. The revenue from this fund has at no time been sufficient, without the avails of a general tax, to satisfy the demands upon the treasury. In order to meet these demands, and to relieve our fiscal affairs from embarrassments, it became necessary, in eighteen hundred and fourteen, to impose a tax of two mills on each dollar of the valuation of real and personal property in the State. This tax was continued until eighteen hundred and eighteen, then it was reduced to one mill; in eighteen hundred and twenty-four, to half a mill, and in eighteen hundred and twenty-seven it was wholly discontinued. When the Legislature refused to continue the tax it was well understood that the general fund could not long sustain the burden cast upon it; that its capital would be rapidly reduced, and soon exhausted. Though this event has not approached so rapidly as was anticipated, it is now at hand, and this session should not, in my judgment, be permitted to pass away without providing the means, by the adoption of some settled plan, to satisfy the demands that must inevitably be made upon the treasury....

"The canals are rapidly accumulating the means for the extinguishment of the debt for which their income is hypothecated. When this object is accomplished, the tolls may, with fair claims of justice, be resorted to, for the means of replenishing the treasury, to an amount, at least, equal to the sum abstracted, for the benefit of the canals, from the general fund." 7

With reference to the method of securing funds, the Governor asks: "Shall we then ... accumulate a debt for the ordinary expenses of the government, trusting to the future appropriations of the income of the canals, for its repayment? ...

"Whether a resort to a general tax, moderate in amount, in order to provide the means to meet the exigencies of the government, shall be forborne, and a reliance be placed on the chance of deriving sufficient aid for that purpose from the duties on salt, and auction sales; or a debt shall be contracted, with a view to its redemption from the canal revenue, after it is relieved from its present hypothecation, are questions which may with propriety be left to the immediate representatives of the people. If upon due deliberation, you should determine to levy a tax, and leave the other revenues unanticipated and unimpaired, ... I feel the fullest confidence that the people will cheerfully acquiesce in the decision." 8

It must be remembered that Governor Marcy was Comptroller in 1827, when the levying of taxes was discontinued, and that at that time he disapproved of the new policy, and remained later, during his occupancy of the gubernatorial office, an advocate of taxes. But popular sentiment was opposed to taxes and they were resorted to in 1842 only as a temporary relief from the exigencies that confronted an almost depleted treasury.

As we consider the subsequent history of this canal improvement, it should be observed how the Legislature, in spite of Governor Marcy’s warnings, proceeded to authorize the enlargement of the Erie and the construction of the Black River and Genesee Valley canals, together with various works upon other lateral branches and a loan of $3,000,000 to the New York and Lake Erie railroad, without any adequate financial plan, trusting to the canal tolls and the salt and auction duties to maintain the waterways and to pay the expenses of the government and the cost of these improvements. When it was seen how slowly the public work must proceed under this plan, the Legislature, in 1838, sanctioned loans, but failed to provide a means for paying even the interest, except by the over-burdened canal tolls or by other loans. Of course such a system could not long survive, and in 1842, aided by a general financial depression of a few years earlier, the limit was reached and it became necessary to enact a law which should "provide for paying the debt and preserving the credit of the State" by imposing a tax and by abruptly stopping all public improvements. These experiences taught the people to restrict the power of the Legislature by what has been aptly termed a "new Bill of rights." This was done in the Constitution of 1846 by the article which required all appropriations of over a million dollars to be submitted to popular vote. After this revised Constitution had attempted to readjust and regulate the financial situation, new troubles arose, which only another amendment in 1854 could remedy. Indeed, from the beginning even to the end of the work in 1862, the lack of funds retarded the enterprise, so that operations were prolonged through a period of twenty-six years, whereas a quarter of that time was probably ample for the whole undertaking, if sufficient funds had been available. For constructing the original canal and for the second and third enlargements, financial schemes were adopted which authorized loans and provided for the payment of both the interest and the maturing principal, but during the first enlargement the very success of the canal seemed to militate against it, for so optimistic a view was entertained that dependence was placed upon the tolls to carry a greater burden than they could sustain. In this connection the arraignment by Governor Young, in 1848, of former Legislatures for their neglect to properly finance the undertaking, is noteworthy. All of these circumstances will be found recorded in their regular sequence. It should be noticed also how rapidly traffic upon the canals increased during this period, with but few backward strides, despite the lack of suitable facilities for transportation.

Still, it is not strange that the people of that day so thoroughly trusted the canals to pay for large improvements, as well as to help defray the expenses of the government, for the canals had succeeded for beyond their expectations. In 1825 the canal commissioners had allowed themselves to make some extravagant predictions, estimating what the tolls on the Erie might be for each year until 1836 and at the ends of the two succeeding decades. They placed the sum at one million dollars for 1836; two millions by 1846, four millions by 1856, and nine millions within fifty years. Thus far the tolls had exceeded this estimate for every year, and the prospects were bright for even a greater increase in the immediate future. Incidentally it may be remarked that in 1836 the tolls surpassed the prediction by four hundred and forty thousand dollars and in 1846 by almost half a million. With the comparatively limited expenses of the State government at that time, and the relatively large income from the canals, the people had begun to think that taxes need never be imposed again, for the waterways were looked upon as a veritable treasure house for supplying funds.

The Governor’s message to the Legislature of 1835 is worthy of notice, inasmuch as it sounded another unheeded note of warning against embarking on so great a scheme of improvement without an adequate financial plan. The Governor said that he regretted that the provision which had been made by the Legislature for doubling the locks on the Erie canal between Albany and Syracuse had not been accompanied by another almost equally necessary, providing for the enlargement of the capacity of the canal, as he deemed it important that the new locks should be made with reference to this latter improvement. However, the new locks were not then constructed and the matter was left to the consideration of the Legislature.

The Governor explained that the State was then facing either a loan, which was objectionable, or a direct tax for general expenses, as the general fund, though not originally intended for that purpose, had been used for several years, without being reinforced by the proceeds of taxation, not only for general expenses, but for large appropriations for deficiencies in maintaining the lateral canals, for draining the Cayuga marshes and the like. Not only was this the case, but specific sources of revenue, like the auction and salt duties, had been constitutionally pledged to the canal fund and had contributed to it more than five million dollars. The burden of supplying the deficiency in the revenues of the lateral canals from year to year, he declared, showed the wisdom of our original system of internal improvements and the effect of such a departure from it, and admonished us of the necessity of returning to it. "No government," he said, "that had a proper regard for its public credit or its permanent prosperity, ever contracted a public debt without providing a revenue for the payment of the interest at least, if not for its final extinguishment; and none that neglects to make such a provision, but supplies its necessities, whether ordinary or extraordinary, by loans, and provides for the interest on them by new loans, can long prosecute successfully public enterprises requiring large expenditures. I therefore deem it essential to the success of the system of internal improvements, that you should in some way provide adequate means for paying the interest on the public debt that must be incurred by its further prosecution." 9

Again he said: "I do not indulge the expectation that so unwise a course will be taken as to supply the means required for these purposes, by loans, without creating some special fund to pay the debt that will be thus contracted." 10 But despite this warning, subsequent Legislatures persisted in pursuing this very course.

However, as showing the continued prosperity of the canals, which warranted the expenditure of large sums for improvement, the Governor stated that the income from all the canals and the canal fund for the fiscal year of 1834 was $1,813,418.73. The whole canal debt was then $7,034,999.68, of which $4,934,652.68 was the unpaid balance of the debt created for the construction of the Erie and Champlain canals. For the payment of the balance, funds had accumulated to the amount of $3,002,576.30 The Erie and Champlain canal fund had yielded a revenue during the last fiscal year, beyond all the charges upon it, of $1,035,664.92; the tolls alone exceeded these charges by $587,850.61. Although the tolls had again been reduced in January, 1834, on merchandise and food-stuffs, the income from the Erie and Champlain canals from these sources alone was $1,313,155.84 for the fiscal year. The tolls of the same year were only $11,265.79 less than those of the previous year. The business on the Erie and Champlain canals had, therefore, increased nearly in the ratio of the reduction of tolls. 11

The improvement of the canal was generally conceded to be a necessity, but opinions widely differed concerning the proper policy to pursue. The sentiment favoring enlargement was no ill-advised, speculative effort, but rather a business-like, earnest movement to benefit the people of the whole state and country by providing a waterway capable of transporting through the state, expeditiously, economically and safely, all the products of agriculture and manufacturing that could be secured for that route. The structures on the canal had largely become impaired and a number would necessarily have to be rebuilt and it was deemed wisest to construct on an enlarged plan and for the prospective traffic rather than to build on the dimensions that were thought sufficiently large at the time of beginning the original canal. At this time every indication pointed to a rapid increase in canal traffic. A glance at the chapter treating of the influence of the canal will show how the prophecies of the projectors had been more than fulfilled, -- in the volume of commerce, the prevalence of general prosperity, the increase of population and the development of western territory.

Two subjects then before the public had a marked bearing on canal enlargement. Of first importance was the growing evidence that railroads were fast becoming a factor in the question of transportation and might soon prove to be dangerous rivals of the canals. Even then those most enthusiastically in favor of railways predicted that they would supersede canals, and advocated the plan of "converting the Erie canal into a rail-road." 12 The second subject was a project for a ship canal between Lake Ontario and the Hudson. Both of these matters received legislative notice during the session of 1835, and were the subjects of Assembly resolutions calling for investigations by canal officials.

The Erie railroad enterprise was then before the Legislature, and wishing to learn the comparative advantages of canals and railroads, the Assembly, on February 28, 1835, addressed a resolution to the canal commissioners, requesting a report on the relative cost of construction and maintenance of canals and railroads, the relative charges for transportation and an enumeration of articles that could be better carried by rail than by water. The commissioners selected the engineers, John B. Jervis, Holmes Hutchinson and Frederick C. Mills, to investigate the subject, and in submitting their report to the Assembly on March 14, 1835, they said:

"It is believed that it will not be difficult to shew, that the expense of transportation on rail-roads, is very materially greater than on canals. In addition to this, there are other important considerations in favor of canals.

"A canal may be compared to a common highway, upon which every man can be the carrier of his own property, and therefore creates the most active competition, which serves to reduce the expense of transportation to the lowest rates. The farmer, the merchant, and the manufacturer can avail themselves of the advantage of carrying their property to market, in a manner which will best comport with their interest." 13

In summarizing their report, the engineers declared their opinion that canals in general had decided advantages over railroads, saying:

"We may, however, be permitted to state, what appears conclusive from the facts presented, that canals, on the average, have thus far, cost less than rail-roads, both in their construction and repairs.

"In regard to their relative matters as affording the means of transportation, ... we find the relative cost of conveyance is, as 4.375 to 1, a little over four and one-third to one, in favor of canals: this is exclusive of tolls or profits." 14

Public sentiment, which demanded that some improvement in water communications be made, was reflected in an Assembly resolution on March 4, 1835, which referred to the consideration of the canal board the proceedings of a public meeting held in Utica on February 5, preceding, to take measures to effect the construction of a ship canal between Lake Ontario and the Hudson, also the resolution of the common council of New York in favor of this canal, together with the report 15 of an engineer, E. F. Johnson, on this project. People were becoming alarmed lest, by the failure of the State to provide adequate means for transportation, other routes would secure the traffic, -- as the memorial prepared at the Utica meeting expressed it, saying, "the States of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia, and especially the Provinces of Canada, are making strenuous exertions to divert the trade of this important region through their own territories, and to their own markets," which "render it the imperative duty of the representatives of the people of this State early to undertake, and vigorously to prosecute, such a system of internal improvement as shall promise the most certain success in this generous contest with their enterprising neighbors." 16 In addition, the memorialists said: "The Erie canal, in its present state, will be unable to accommodate any material increase of business; and ... unless some adequate measures are adopted by the Legislature to secure to this State the advantages of the rapidly increasing trade of the western country, it will seek other channels of transportation and a different market, to the great prejudice of our commercial metropolis, and the loss of revenue and other incidental advantages derived from the passage of that trade through our own internal communications.... The plan of doubling the locks, recently adopted on a portion of the Erie canal, though it will doubtless increase its capacity, will afford but a temporary relief; and before that measure can be completed, the steady increase of the business will be found to have kept pace with the increased facilities which will be thus afforded; presenting to us the same alternative which now exists, of creating additional channels, or of yielding to others the benefit of the trade in question." 17

In reporting the results of their investigations on this subject, the members of the canal board conceded that some measures should be adopted to provide for the increased traffic, but disagreed with the Utica memorialists in thinking that a ship canal for either sailing craft or steamboats would be best adapted to meet this need. The difficulty of bridging such a canal seemed insuperable. The fact that steamboats had not yet superseded sailing vessels in carrying property on the lakes led the members of the board to believe that they were not destined so to supersede that kind of boat for the transit of property on lakes or rivers adapted for the use of both, they having been informed "by gentlemen of intelligence and experience in lake navigation, that it would be ‘impracticable as a regular business for steam-boats on the lakes, to tow vessels with safety, unless the vessels were fitted with masts and rigging and sufficiently manned to be conducted by sails in a storm.’ " 18

The report of the board’s engineers, Messrs. Jervis, Hutchinson and Mills, further emphasizes the fact that steam propulsion was not sufficiently developed to be serviceable on contracted channels, and that the cost of carriage by steamboats was not favorably comparable with the rate by ordinary canal-boats, even after the charge for a transshipment had been added. They conclude: "We are of opinion, a canal, designed for boats exclusively adapted to its navigation, and which may be towed by steam-boats on the Hudson, will best accommodate the prominent interest involved in the great trade, for which provision is to be made." 19

In their report the members of the board take occasion to express their views on the proper course for the State to pursue, saying: "The canal board entertain the opinion, that an enlargement of the Erie canal would be, in all respects, the best plan to accommodate the transportation between the Hudson river and the western lakes....

"At the last session of the Legislature a law was passed, directing the Canal Commissioners to double the locks, from Albany to Syracuse. This measure will increase the capacity of the canal, and accommodate the trade for a short period of time, but will not sensibly lessen the expense of transportation. It is however quite certain, that the time is not very distant when additional facilities will be necessary; and the Canal Board take this occasion to express the opinion that the enlargement of the Erie canal should be directed at the present session of the Legislature." 20

The result of this agitation was the passage of a law (chapter 274), on May 11, 1835, which authorized the canal commissioners to enlarge the Erie canal and to construct a double set of lift-locks, as soon as the canal board believed that public interest required such improvement. The questions of dimensions and of constructing an independent canal through cities and villages, instead of enlarging the existing works, were left to the determination of the canal board. At a meeting on July 3, 1835, the canal board adopted resolutions declaring that the work of doubling locks and of enlarging the canal should be commenced without delay, and that surveys should be started immediately. The canal commissioners, meeting at Utica on July 17, 1835, determined what considerations should govern the surveys for an enlarged canal. Estimates of cost were to be made for enlarging the prism to six feet depth of water and sixty feet width at water-surface, and also for a canal seven feet deep and seventy feet wide, except at difficult and expensive points, such as perpendicular bluffs or marshes, where the width could be limited to fifty feet. A study of additional water-supply was to be made, with a report on the formation of new feeders and reservoirs, and the engineers were asked to report also on the expediency of two separate canals in villages and cities where widening would cause the removal of buildings at considerable expense, and their opinions were desired in regard to the dimensions of locks best adapted to economy in transportation, for both sizes of enlarged canal.

The engineers in charge of these surveys and the territory covered by each, were as follows: John B. Jervis, from Albany to Fultonville; Nathan S. Roberts, from Fultonville to Frankfort; Frederick C. Mills, from Frankfort to Lyons; and Holmes Hutchinson from Lyons to Buffalo. The reports 21 of the engineers were submitted to the canal board on October 20, 1835, with estimates of the cost of contemplated improvements on both plans of enlargement, and of all the feeders and reservoirs required.

The reports treated at length of the size of aqueducts, the size of new locks and the dimensions of the improved canal, with carefully prepared recommendations on each. Mr. Jervis advised that the trunks of aqueducts be made fifty feet wide, with spans of eighteen feet between piers; that the locks be one hundred and ten feet long between quoins and sixteen feet wide, being placed in pairs, side by side, forty feet apart from center to center. He estimated that for favorable traction the old canal was adapted to a boat of thirty-one tons, a six-foot canal to one of seventy-one tons and a seven-foot canal to one of one hundred and three tons. He advised a seven-foot canal with seventy feet top width, showing that a seven-foot channel would require thirty-seven per cent more water than the old canal. Mr. Roberts favored a lock one hundred and ten feet between quoins and seventeen feet wide, and a canal six and one-half feet deep and seventy feet wide. Mr. Mills submitted plans of bridges for a seventy-foot canal in the type of the lattice Town. He estimated locks one hundred and ten feet long and sixteen feet wide. In relation to the water-supply for the eighty-five miles included in his section, he estimated that the old Erie required 13,755 cubic feet per minute, that 21,644 cubic feet would be needed for a six-foot depth and 25,147 cubic feet for a seven-foot canal. The report of Mr. Hutchinson gave complete specifications for the manner of constructing double enlarged locks, the basis for the specifications subsequently used in the construction. For the enlarged canal he advised forty-two feet bottom width, seventy feet top width and seven feet depth; locks one hundred and fifteen feet by seventeen feet; size of boats, one hundred and three feet long, sixteen feet wide and five feet draught, with a tonnage of one hundred and sixty-nine tons, exclusive of boat; cost of transportation, he estimated, would be one-half that by the old canal or, more exactly, as 0.54 to 1. The aggregate of the estimates, including the cost of a double set of lift-locks on the whole line, was: for the larger canal, $12,416,150.17; and for the smaller canal, $10,368,331.48. 22

To decide the dimensions to which the canal and locks should be enlarged was a question of so great responsibility, and one concerning which there was such a diversity of opinion, that the canal board felt that it must be dealt with most carefully. To change the boundaries of the canal necessitated the interference with private property, and the officials appeared to view this as a very delicate question, and they hesitated before making their decision, considering that the idea of disturbing the bounds of the canal for a second enlargement could not be entertained. After carefully weighing all of the information derived from the surveys and from other sources, the board decided that the canal should be enlarged to seven feet depth of water and seventy feet width of surface, and that the locks should be one hundred and ten feet long between the quoins and eighteen feet wide. As it was estimated that the enlargement of the canal would lessen the expense of transportation, exclusive of tolls, about fifty per cent, the board deemed it necessary to commence the work as soon as practicable, and to prosecute it with as much diligence as the funds appropriated to this object would admit.

The law authorizing the enlargement provided that the cost of constructing and maintaining the work should be paid out of any monies which might be on hand belonging to the Erie and Champlain canal fund. The funds at the disposal of the canal commissioners were too limited to justify a commencement of work on every part of the canal. It was, therefore, deemed advisable to confine operations to the line between Albany and Syracuse, until such time as the funds would justify a beginning on the other parts of the route. This arrangement would relieve the greatest crowding and thus, in a large measure, secure the advantages of an enlarged canal before the whole could be completed.

In his message to the Legislature of 1836, Governor Marcy reiterated his warning against endeavoring to carry on public works without an adequate financial plan, but this, like his former plea, passed unheeded. He said: "I have not been without apprehensions, and I still entertain them, that internal improvements cannot be long prosecuted on an extensive scale unless sustained by a wise system of finance. No new work can be executed without using the public credit, and however high that credit is at this time, it cannot be liberally used and long upheld without some financial arrangement that will inspire confidence at home and abroad.... The improvident practice of borrowing money without providing available funds for paying the interest, has already been carried to a point beyond which it cannot be pushed without producing serious mischief.... On a part of the debt already contracted for internal improvements, the interest can only be paid by new loans, unless you resort to taxes of some kind; ... Very few, I should hope, would advocate the reckless policy of contracting a debt, even for such an object, and constantly and rapidly accumulating it by loans to pay the interest.... Can we claim the continuance of public confidence on the assumption that a future generation will take better care of public credit than we are willing to do? ... The treasury is entirely exhausted, and you are therefore required to provide for the support of these canals, and to pay the interest on the debt contracted on their account for the present year, more than one hundred thousand dollars." 23

As early in the season of 1836 as the weather would permit, the greater part of the line from Albany to Buffalo was reexamined by the engineers. Experience during the previous decade had disclosed the places where the canal could be bettered in the plan of construction and in location, and the engineers determined to avoid some of the inconveniences to which navigation had been subjected. Especially troublesome were the short pound-reaches that were located at the nine locks above the junction of the Erie and Champlain canals, at the three locks close by and at the four locks above Cohoes falls. With the locks lengthened and the boats enlarged, the reaches would become still shorter and more troublesome. Therefore, after a very careful examination, the canal board decided in favor of an entirely new location for a distance of four and a third miles, leaving the old line about one and a half miles above West Troy and joining it again above the four locks. The estimates showed this plan to be more expensive than to enlarge the old route, but its importance and decided advantages were considered to more than counterbalance the difference in cost. The locks could be so located as to give convenient pound-reaches between them, and the lifts could be so arranged as to reduce their number from nineteen to sixteen, without making any lift more than ten feet.

The question of changing the location between Cohoes and Schenectady from the north side to the south side of the Mohawk was very important, and one that divided the members of the canal board. It will be recalled that this was one of the most difficult portions encountered in locating the original canal, and that then the best solution was thought to be the crossing of the river twice on long aqueducts rather than the attempt to remain on the south side. At this time, however, after thorough examinations, the engineers reported the change feasible. To dispense with two aqueducts across the Mohawk was very desirable, and also the possibility of doing the work in the most favorable season of the year, and under circumstances of less embarrassment than on the old line, was an argument with weight, but the idea of abandoning about thirteen miles of existing canal, where damages to private property had been assessed and paid, and business establishments had been built up, and where the damages by reason of enlarging the canal would be very limited in comparison with those on a new route -- this idea was calculated to make a strong impression against so material a change. The final decision was in favor of the old line. A rumor, which, however, cannot be substantiated from the records at hand, has gained considerable credence to the effect that the desire to gain needed political support and to please the people of Saratoga by not removing the canal from their county played a large part in influencing the decision.

Among the other important changes may be mentioned those at Utica. Here the width was to be contracted to sixty feet through the central part of the city; this contraction was adopted to avoid extensive damages to private property, although somewhat inconvenient for navigation. The surface of the water at this place was not much above the level of the street. To raise the water three feet would require the bridges to be elevated to an inconvenient height, and would materially injure the business located near the canal. To obviate these objections, the bottom of the canal was to be lowered three feet through the city and to the end of the Frankfort level. This plan would render it necessary to construct a three-foot lift-lock near the western boundary of the city, but would retain the surface of the water in the enlarged canal at the same elevation as in the existing canal.

It was decided to change the location of the aqueduct at Sauquoit creek to a position a few rods farther down the stream; this would straighten and improve the alignment. It was also decided to change the location of the aqueduct over the Oriskany creek and to change the line of the canal on each side of it, carrying the canal on the north side of the Oriskany factory. This change required a new canal for about half a mile in length. These alterations not only improved the alignment of the canal but permitted the construction of the aqueducts during the season of navigation, the most favorable time for work.

The two locks at Lodi (now eastern Syracuse) were found to be in such a dilapidated condition as to require rebuilding. They were placed very close together, leaving but a short pound-reach between them. To remedy this inconvenience it was decided to change the location of the upper lock, carrying it twelve chains farther east, and there to build a set of double locks on the enlarged plan. It was also decided that the location of the lock at Syracuse should be ten chains east of the existing lock. This had a lift of only six feet, but as the Syracuse level was to be cut down two feet, the enlarged lock would have a lift of eight feet. The stone aqueduct over Onondaga creek, which partially failed in the summer of 1834, and over which navigation had been kept up by a wooden trunk of the width of a single boat, was required to be rebuilt for the enlarged canal. The enlargement through Syracuse was so intimately connected with the construction of the locks and the aqueduct, that it was determined that work for about three miles should be put under contract at once.

Beginning August 22, 1836, a number of proposals were received for constructing various sections and structures of the enlarged canal. The majority of the work for which proposals had been made was put under contract, the balance not being let because the bidders did not procure the necessary security to insure the faithful performance of their contracts. Many of the contractors began work in this year. The estimated cost of the work under contract was $3,035,087.44. The canal commissioners stated that, had not the enlargement been authorized, $550,000 of this amount would have been required for necessary repairs, and they further stated that according to their calculations the amount let in this year would consume the tolls applicable to enlargement for 1836-7-8-9, and, therefore, under these conditions, no more work could be let until 1839. Moreover, they deemed it their duty to state that there were several places on the canal where its immediate enlargement would be advantageous to navigation. So important did they consider this subject that they reiterated the statement in their annual report for the following year (1837), and they added that they believed that public interests would be essentially promoted by as speedy a completion of the whole canal as "the facilities for obtaining means and proper economy in reference to the expenditure" would justify.

By the first of July, 1836, the surplus revenue derived from the Erie and Champlain canal fund had amounted to a sum amply sufficient to pay off the remainder of the debt ($3,582,502.73) contracted for the construction of these two canals. By this event the auction and salt duties were discharged from the constitutional pledge securing them to that fund and were restored to the treasury for general purposes. But there was yet a further canal debt of over three million dollars, contracted on account of the Oswego and lateral canals, on which, as payment from their several revenues was the sole source of funds for extinguishment, the prospect of discharging the debt was considered very faint and distant. The total tolls for the year ending September 30, 1836, on the Erie and Champlain canals, was $1,548,536.18 and the whole income of the fund belonging to these canals from all sources was $1,947,483.61; and after deducting all expenses, the net revenue was $1,341,934.36. 24

During the legislative session of 1837, there appeared the first intimation that the enlargement would cost more than the amount reported a year before. In reply to a Senate resolution of February 21, "whether from the surveys, examinations and estimates [then] possessed, they [believed] said enlargement [could] be completed at the cost heretofore estimated, and if not, at what additional cost, including damages to individuals," 25 the canal board said that they did not believe that the work could be completed for the sum previously estimated, because plans for some of the structures had been changed, parts of the alignment had been altered and probably other deviations would be made, and the cost of construction was greater than when the estimates were made. They had no further surveys on which to base their opinion, but they did not believe the additional cost would be large, exclusive of damages, the amount depending upon the prices of labor and materials. No estimates of damages had been made, as the statute provided that these should be adjusted by three appraisers appointed by the Governor and the Senate." 26

During 1837 several important changes were decided on by the canal board. A new location at Rome had been authorized by a special act 27 of the Legislature. It will be recalled that the original Erie canal had been built about half a mile south of the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company’s works, which had extended through the southern part of this village, and that, at the time of the celebration attending the opening of the canal in 1825, the villagers had shown their disapproval of the change by marching through the streets to the solemn beat of muffled drums. The surveys of routes by the old canal and by a new line were reported to the commissioners on May 25, 1837. The estimates showed a difference of $22,590.85 in favor of the existing location, but by the adoption of the new line the construction of a section of the Black River canal would be obviated, which was estimated to lessen this amount by $9,000. The saving of about half a mile of distance on the Black River canal and of eleven hundred feet on the Erie, and the advantages of better accommodations for the citizens of Rome were counted as benefits to outweigh the additional cost. Therefore, it was determined to construct an independent canal, which brought the course back to near the location of the old Navigation Company’s channel.

Another important deviation was at the Jordan level. What was known as the Jordan level of the old canal was a summit level, twelve miles long, having a lock of eleven feet lift at each end. It was decided to cut this level down, thus dispensing with the locks. Two lines were surveyed for an independent canal -- one to the north and one to the south of Lamberton’s hill. The line to the south was decided by the canal board to be the more advantageous, commencing a short distance east of the lock at Nine Mile creek, which was taken in as a feeder, and running south of the old canal about two miles, where it crossed the old channel, and then continuing on the north side to the village of Jordan. This change would save one mile in distance and $18,323.72 in cost, besides the annual expense of repairs and attendance of a set of double locks at each end of the level.

The commissioners reported that a large amount of work had been done on the locks during 1837, but not as much as had been desired, and that the contracts for other structures and for canal sections had progressed satisfactorily. In closing their report they made a strong appeal to the Legislature of 1838 for a more liberal supply of funds, in order that the undertaking might be pushed with vigor, calling attention to the reduced freight rates and the increased tolls that would follow its completion.

Reviewing the situation of 1837, Governor Marcy, in his message, admitted a falling off of $275,000 in tolls from those of the previous year, the gross amount being but $1,326,781 for the fiscal year. Used as channels of trade, the canals necessarily participated in its fluctuations. In consequence of the scanty crops of 1836, the eastward tonnage was diminished, as was also the amount of merchandise sent westward. The income of the Erie and Champlain canal fund, from all sources, was $1,426,071.78. Of this amount $632,881.20 was expended on the enlargement of the Erie. The estimates for unfinished works of internal improvement, including enlargement of the Erie canal, were $15,000,000. The completion of the aqueduct at Rochester was urged as a necessary measure to keep up the business of the canal in case of the failure of the old aqueduct. In the Governor’s opinion a still larger appropriation might be advantageously used for improvements. The channel of the Erie canal, he said, was at least as eligible for western trade as any that could be opened and both duty and interest required that it should be made adequate to the public wants without delay. The Governor recalled his previously unheeded messages as to the necessity of a financial system to meet the interest charges and ultimately to extinguish the principal of the public debt. 28

The appeal of the commissioners for funds brought a response in the form of a law, directing a loan of four million dollars, but before its enactment the Assembly adopted a resolution which reflected the growing sentiment that the State had under taken too large an enterprise. The effect of the financial panic of 1837, with its suspension of specie payments, was becoming evident. This resolution called for an opinion from the canal commissioners as to the most practical plan for completing the work of doubling locks, without the immediate enlargement of the prism. In reply the commissioners said, that, after the act of 1835 had directed the enlargement of the Erie canal, they had regarded the policy of the State on that subject as settled, and had made all plans and arrangements on that supposition, but they added that no work had been placed under contract that was not necessarily connected with the use of the new locks, except short sections at Albany, Utica and Syracuse. However, if the whole project could not be completed, they recommended that certain necessary portions be undertaken, saying:

"The work for the enlargement of the canal not under contract, that in the opinion of the Commissioners ought to be immediately commenced is: the doubling of the locks from Albany to Syracuse; taking in additional feeders and enlarging the canal near the locks; rebuilding the lower aqueduct across the Mohawk river, building aqueducts over the Schoharie and several other creeks between Schenectady and the Little-Falls; enlarging the canal through the east part of the city of Utica and building an enlarged weigh-lock at that place; re-building the aqueduct over the Oneida creek and enlarging the canal at the ends of it; cutting down the Jordan level and taking in a feeder from the Nine-mile creek; building an enlarged weigh-lock at Rochester; and enlarging the canal through the mountain ridge, re-building the locks at Lockport, and the guard-lock at Pendleton." 29

To carry out this recommendation the Legislature enacted a law 30 authorizing the commissioners of the canal fund to borrow four million dollars on the credit of the State, and directing the canal commissioners to put under contract, with as little delay as possible, such portions of the work as their report had described in the paragraph just quoted, and also "such other portions as in the opinion of the canal board [would] best secure the completion of the entire enlargement, with double locks on the whole line." The canal board decided that the additional parts should be the Irondequoit embankment and the heavy embankments in the Mohawk valley. During 1838, the work authorized by the law was put under contract, except at the Irondequoit embankment, which was delayed to make surveys for a new route. It was alleged by certain petitioners of Monroe county that a saving of several miles could be made. Although the survey verified this statement, it showed the cost by the new line to be more than twice that by the old, thus causing the canal board to decide on the enlargement of the existing canal.

At several places in the valley of the Mohawk river navigation was often interrupted by the streams that crossed the line of the canal. In planning the enlargement in this valley, one great object was to cross on aqueducts all the large streams, which were then taken into the canal. This was considered indispensable. Perhaps the most troublesome of these had been the Schoharie creek. On the west bank of this creek the canal was locked into the stream, which it crossed in a pool formed by a dam across the creek. At a point four miles above there was another lock, and about midway on this section the canal crossed another large creek in the same manner. These were turbulent streams and occasioned much trouble to navigation. Accordingly, it was determined to raise the level of the canal sufficiently to cross both streams on aqueducts. It was also decided to cross Indian Castle creek and the streams at Fort Plain, Canajoharie and Sprakers by aqueducts.

The engineers estimated that the cost of the work then in progress (1838), at contract prices, would amount to $10,405,913.38, exclusive of engineering, superintendence and contingencies. This estimate clearly indicated that the total expense of enlarging the canal would greatly exceed the amount reported in 1836. In explaining this difference, the canal commissioners stated that the estimate given in 1836 was made in 1835, while the question of dimensions, was still pending, and that it was made chiefly for the purpose of showing the comparative costs of the two proposed sizes. They declared that the surveys and estimates were made in too short a time -- three months -- to allow the making of well-developed plans or a proper study of conditions. Many necessary changes and improvements had greatly increased the cost. They called attention to the fact that the law authorizing the work of enlargement was passed in 1835, before the estimates had been made, and accordingly the amount reported in 1836 should not be taken as the basis for legislative action; also that the canal board, in submitting the estimates to the Legislature in 1836, was careful to state that, although they were made with all practicable care and correctness, they could not be considered with much certainty, and great allowance should be made for the short time and the difficulty of estimating under existing circumstances.

The aggregate canal tolls and water rents for the fiscal year, 1838, were stated in Governor William H. Seward’s ensuing annual message to be $1,481,602.41. Repairs and collections, now termed maintenance, were $639,714.32, leaving net proceeds of $841,888.09. The gross income of the Erie and Champlain canal fund was $1,553,136.84. Of this $449,058.64 had been expended for repairs, $129,374.05 for interest and $26,892.65 for sundry payments, leaving a balance of $947,811.50 in the fund. During the same period the commissioners expended $1,161,001.80 on the Erie enlargement. Under the act of April 18, 1838, they borrowed, including premiums, $1,005,050, leaving a deficiency of $155,951.80, which was also paid from the above surplus, reducing the fund to $791,859.70. Moreover, the tolls of the laterals were but $58,264.76, while their expenses, including interest on construction funds, were $229,160.59, and this deficiency was, as usual, loaded upon the fund, still further reducing it to $562,699.11.

The Governor advocated limiting the term of office of the canal commissioners to bring them within closer reach of the appointing power, in the interests of economy. One-fourteenth of the sum received for tolls was expended in salaries and, including repairs, almost one-half of the entire tolls was absorbed. Such a system, he thought, was without doubt capable of advantageous revision. With extended improvements the official power and patronage of the commissioners and the canal board had been enlarged to an immense and unlooked-for extent; but little publicity or accountability was required; a great, mysterious and undefined power had thus grown up unobserved, while the public had been narrowly watching less important functionaries. It was suggested that a board of internal improvements, composed of a number from each senatorial district, would be more economical and efficient. "It is the worst economy," said the Governor, "to devolve upon officers constituted for one department, duties appurtenant to others. Its universal results are diminished responsibility and diminished efficiency in both the principal and incidental departments." 31 This was in the line with Governor De Witt Clinton’s suggestion of a "board of public improvements," made in 1822 and renewed in 1825.

Governor Seward took a much more hopeful view of the financial situation than had his predecessor, seeming to reflect the popular sentiment that the canals were fully able to pay the cost of enlargement. He said: "Taxation for purposes of internal improvement is happily unnecessary as it would be unequal and oppressive ... The present resources and credit of the State shew that the most ardent advocates of the [canal] system failed altogether to conceive the vast tribute which it has caused already to flow into the treasury.

" ... their productiveness would warrant the State in expending in internal improvements $4,000,000 annually during a period of ten years; ... the revenues of the canals alone would reimburse this expenditure previous to the year 1865 ... It [the State] has increased four-fold the wealth of its citizens, and relieved them from direct taxation; and in addition to all this has carried forward a stupendous enterprise of improvement, all the while diminishing its debt, magnifying its credit, and augmenting its resources." 32

However, the Governor saw the danger that might ensue. Continuing, he said : "This cheering view of our condition ought to encourage neither prodigality of expenditure nor legislation of doubtful expediency.... Rigid economy ought to be enforced, and perfect accountability exacted." 33

In answer to an Assembly resolution of February 20, 1839, the engineers submitted to the commissioners a report 34 of the cost of work completed, of that under contract and also of that yet to be put under contract, including amounts for engineering, superintendence and contingencies. This estimate amounted to $23,402,863.02. The following statement of the main items that were omitted in the estimate of 1835 shows to some extent in what the difference between the two estimates consisted: -- damages, about seven per cent; enlarging the West Troy side-cut and doubling its locks; five additional aqueducts in the Mohawk valley, including necessary changes of the canal at those places; additional width of excavation through the mountain ridge at Lockport and at various points on the line; additional width to the berme and towing-path embankments; two weigh-locks; five weigh-lock houses and scales; increased dimensions, and improved quality masonry in locks, aqueducts, culverts and bridges, increased amount of slope wall -- the estimated cost of these items was $6,143,969. This amount together with $12,416,150 -- the estimate of 1835, -- increased by thirty-three per cent, or $4,097,329.50, for the rise in the cost of labor, provisions, team work, etc., makes a sum total nearly equal to the estimate just stated.

The only act, passed at the session of 1839, which appropriated money for purposes of internal improvement, was one directing that $75,000 be used for improving the navigation of the Oneida river.

The gross receipts of the canals for 1839 (fiscal year), including water rents and land sales, were $1,656,902.11. The ordinary charges were $459,987.59, to which was added $139,111.78 for the Glens Falls feeder, the Black River canal and feeder and the Tonawanda and Ellicott creek improvements and payment of previous liabilities under special acts, leaving the net tolls $1,057,802.74. 35

The canal commissioners reported that a large amount of work had been done on the enlargement during 1839, but not so much as was contemplated, because, on account of the anticipated difficulty in obtaining the balance of the loan authorized in 1838, the contractors had not been pressed to a vigorous prosecution of their work. With the uncertainty of being promptly paid for their labors, the contractors had preferred to proceed with caution. This uncertainty was due to the deplorable condition of the State’s finances. The sudden and calamitous revulsion in the business prosperity of the entire nation, which had culminated in the panic of 1837, the cessation of specie payments by the banks, the fear that the worst was yet to come, and above all, the persistent draining of the treasury for expenses of government and works of improvement, through the failures of the various Legislatures to provide an adequate system of finance -- such conditions tended to cast an all-pervading gloom over the people and to cause them to lose confidence in the solvency of the State. The result of this state of affairs was of course felt by the canal authorities. Money could not be readily borrowed and the stock brought very small premiums; in fact the credit of the State was in jeopardy and, although the enlargement was looked upon as a necessity and much had been done already, it became necessary to curtail expenditures in order to protect and rehabilitate the credit of the State.

Governor Seward, in his message to the Legislature of 1840, endorsed this idea of retrenchment, but favored the plan of proceeding with as much energy as the circumstances would allow, saying:

"During the severe [financial] pressure we have experienced, the industry of the citizen has been stimulated, and the wages of labor, the prices of the products of the earth, and the value of property have been sustained by expenditures in the prosecution of this [canal] system. The sudden arrest of such expenditures, and the discharge of probably ten thousand laborers, now employed upon the public works, at a time when the circulation of money in other departments of business is so embarrassed as almost to have ceased, would extend throughout the whole community, and with fearful aggravation, the losses and sufferings that as yet have been in a great measure confined to the mercantile class."

Referring to the project of enlarging the canal, he said: "The act of 1835 directed the enlargement to be undertaken when the canal board should be of opinion that public interest required the improvement, and its extent was submitted to their discretion. It will not, I hope, be deemed disrespectful to remark that the first step in the great undertaking, the delegation of the legislative power to a board not directly responsible to the people, was a departure from the spirit of the constitution, so unfortunate in its consequences, that it should remain a warning to all future legislatures. The expense of the enlargement is now estimated at $23,402,863; yet the law by which it was authorized passed without any estimate having been submitted to the Legislature, and with scarcely any discussion. If completed on the present scale, the canal will surpass in magnitude every other national work of internal improvement; yet all the responsibilities in reference to the dimensions and cost of the enlargement seem to have been cast off as unworthy the consideration of the Legislature." In reference to the revised estimate for the completion of the Erie enlargement and the Black River and Genesee Valley canals, he continued: "The confidence of the people in the policy of internal improvement, has sustained a severe shock from the discovery that the state was committed by the Legislature to an expenditure of thirty millions of dollars, for the completion of three works alone, upon estimates of the same works rising only to about fifteen millions." 36

The Governor devoted the greater part of his message to an advocacy of the canals, but admitted that "apprehensions prevail that the public credit may become too deeply involved in the prosecution of works of internal improvement." "The policy indicated by public sentiment," he said, "and demanded by the circumstances of the times and the condition of the state, is to retrench the expenditures upon our works of internal improvement and prosecute the system with moderation and economy." In regard to securing funds for public works, he said: "The existing and anticipated revenues of the canals must be, as heretofore, the basis of any new loans which the Legislature shall see fit to authorize, since taxation for purposes of internal improvement deservedly finds no advocate among the people." And he added, -- in a vein which showed with what confidence the canals were looked to for supplying funds: "Unlike other communities, this state borrows no money for purposes of war or defence, to pay salaries or pensions or the interest or principal of former loans, or even to endow institutions of learning, benevolence or religion. Her income is sufficient for her wants, without taxation; the value of her productive property is double the debt she owes; her surplus income is double the interest she is required to pay; and the revenues derived from her canals, if judiciously managed, will be adequate to every enterprise which the interests of the people shall demand." 37

Mr. George W. Lay, member from Genesee county, of the committee on canals and internal improvements, to which was referred so much of the message as related to canals and internal improvements, agreeing with the Governor, thus reported: "The present condition of the finances of the country, and the general embarrassment pervading every portion of the United States, in consequence of the deranged and unsettled state of the monetary affairs, has had a tendency alike to alarm the timid, and shake the confidence of the more cautious, in regard to the policy to be pursued in future, as to our system of internal improvements." 38

Continuing, the report says: "The enlargement of the Erie canal to the dimensions fixed and established by the Canal Board has been for the last three years considered as a question definitely settled. It was a subject deliberately examined, thoroughly investigated and discussed, and as solemnly adopted. No trivial, transient, temporary cause now existing, ought, for one moment, to disturb or unsettle a decision so important to the interest of the people, and the prosperity and credit of our State. It is not now to be decided whether the people would have consented to adopt the several projects which have involved the State in the expenditure of the large sums of money which will be required for their completion. Had they foreseen that the estimates upon which these works were based would prove so entirely inadequate; or could they have anticipated so sudden and unexpected a revulsion in everything connected with the business and prosperity of our country, your committee are satisfied that more cautious counsels would have prevailed, and we should not now be called upon to deliberate and decide what measures should be adopted to guard the honor and credit of our State, and protect the right and property of our citizens.... The representatives of the people approved of the undertaking, and year after year they have given the most unequivocal demonstrations that their confidence in the utility and value of public improvements, judiciously made and carried on, remains unshaken." 39

In spite of repeated assertions from canal officials that nothing short of an enlargement of the whole canal would afford more than temporary relief, the Assembly again raised the question of abridging the enterprise. In reply to a resolution of March 2, 1840, asking the canal board "whether, in their opinion, any change [could] now be made advantageously to the public interests in the plan, dimensions or manner of execution of the work adopted for the enlargement of the Erie Canal, so as to lessen the expense of that work; and also, how long a period of time [would] be required to complete most advantageously to the public interests, the enlargement of said canal;" 40 the officials answered 41 that, in their opinion, no changes ought to be made in the plan, dimensions and manner of executing the work. The object of the enlargement was to remedy those defects which had been so frequently explained. To change the plan and dimensions, they argued, would be to defeat the very object of the enterprise, namely, to cheapen transportation and to accommodate the increasing traffic. Moreover, to vary the details of existing contracts, especially after much progress had been made in their performance, would be vexatious, embarrassing and difficult. With regard to the structures thereafter to be put under contract, the board was of the opinion that a cheaper style of masonry could be adopted for bridges, culverts and aqueducts, but such a change would impair their strength and durability. As to the time required to finish the enlargement of the canal, that would depend upon the resources of the State, and the Legislature would be able to determine in each year the amount of work that could be judiciously undertaken.

The Legislatures of 1840 and 1841 were constrained to adopt a policy of retrenchment. However, they persevered in the construction of public works, but with moderation and economy, trying to guard against a dangerous increase of debt and the possibility of taxation, in order that the whole debt of the State might be kept within such bounds that the interest should not exceed the net revenue from canal tolls, and that any increase in the revenue might be applied to the payment of the debt.

During 1840 a loan of $2,000,000 for the Erie, $500,000 for the Genesee Valley and $250,000 for the Black River canal was authorized, 42 and in 1841 another 43 of $2,150,000 for the Erie, $550,000 for the Genesee Valley and $300,000 for the Black River. As indicating the anticipated stoppage of all work in the near future, it is significant to notice that, with the exception of a lock at Black Rock dam and some work at Rochester, these acts restricted all operations to such as were necessary to render available the work then in progress and to prevent the interruption of navigation. During 1840 very satisfactory advancement was made, the season being unusually favorable, and the effect of the suspension of public works in neighboring states becoming manifest in the reduced price of almost every kind of labor and material. In 1841, however, the need of funds was more severely felt, not enough being available to complete the work within the time specified in the contracts.

To digress a moment, we observe that during the legislative session of 1840, a concurrent resolution was passed, giving consent to the construction by the Government of the United States of a ship canal around the falls of Niagara, and requesting the Senators and Representatives of the State in the Congress of the United States to use their best efforts to secure the passage of a bill for this purpose.

Still digressing, we notice another interesting fact. "The first bridge in America consisting of iron throughout," said one recently, "was built in 1840 by Earl Trumbull over the Erie Canal, in the Village of Frankfort, N.Y. In the same year Squire Whipple, Hon. M. Am. Soc. C. E., also built his first truss bridge." 44

The gross receipts of the canals for tolls and rents for the fiscal year 1840 were $1,606,827.45 and the gross charges, exclusive of interest on loans, $586,011.87, leaving a net revenue of $1,020,815.58, a slight falling off from the previous year. But the tolls and rents received during the entire season of navigation were $1,775,747.57, showing a gratifying increase of $159,365.55. The canals were navigable from the twentieth of April to the fourth of December. The depth of water and consequently the tonnage of boats was increased, thus reducing expense of transportation. The Erie enlargements were prosecuted with vigor so far as permitted by appropriations. The amount expended for this enlargement prior to January 1, 1840, was $4,669,661. The appropriations and canal revenues of that year were $2,869,171, making an aggregate for this work of $7,538,832. In reviewing the year’s work, the Governor said that the experience of the present commissioners justified the belief that the cost of the enlargement would not exceed the corrected estimates of 1839, or $23,112,766. There would, therefore, be required to finish the enlargement, $15,573,934. That portion lying between Albany and Rome, said the Governor, might be completed in the spring of 1843; the part extending from Rome to Rochester by the spring of 1845; and the residue, from Rochester to Buffalo, by the spring of 1847. 45