FORESTER and Marco Paul remained a day or two at Albany, making their investigations in respect to the canal; and they final]y concluded that their first excursion in visiting it, should be to go to Schenectady, and there take a packet-boat and sail to Little Falls, a village about fifty miles beyond Schenectady.

The reason why they went to Schenectady, instead of beginning their voyage upon the canal at Albany, will be made apparent by looking at a map of the State of New York, awl a profile of the canal. It will be seen that from Albany to Schenectady the canal ascends rapidly, by a great many locks, up the valley of the Mohawk; and it takes also a circuitous route. The ascent is to be seen by the profile [*Link to map and profile], and the circuitous course by the map. Now the heavy goods which are transported along the canal must necessarily be taken round that way. The delay is not of much consequence to the merchandise; but passengers, who wish to get to the end of their journey as soon as possible, generally go across from Albany to Schenectady by a railroad, and then take the canal there. The consequence is, that there are no passenger boats going from Albany to Schenectady, but only boats for carrying merchandise. The boats for passengers are made very different from the boats for merchandise, and they are called by different names. The passenger-boats are called packets, and the others are called line boats.

Now, though a great many emigrants travel in line boats, Forester knew very well that they would not be at all comfortable to those who had been accustomed to the conveniences and refinements of life; so he concluded to proceed directly to Schenectady by the railroad, and take the packet-boat there.

And the reason why Forester and Marco concluded to stop at Little Falls, was, because they found, by the description of the canal in their books, that there was a remarkable feeder at Little Falls, a feeder in which the water was brought into the canal by an aqueduct built across the Mohawk river. This aqueduct may be seen represented on the large maps of New York. The books said also that the scenery at Little Falls was very romantic and grand, and that there were several locks there too. So that by visiting Little Falls, they found that they would have an opportunity to see locks, and a feeder, and an aqueduct, and romantic scenery besides.

There was another thing which they hoped to accomplish, too, on this excursion. They found, on inquiring at Albany, that a packet-boat left Schenectady every night, and another every morning. Now they wished very much to spend a night on board a boat on the canal; for they wished not merely to see the canal as a mechanical structure, but also to witness some of the various scenes of human life which were presented in connection with it. One of these scenes was a night in a packet-boat; and they calculated that if they took a night boat at Schenectady, they should accomplish that object; and then afterward, in the morning, before they reached Little Falls, they would have time to sail along for some distance by daylight, and see the country and villages, and observe the incidents which occur along the balls of a canal.

"We will take very little baggage," said Forester, "so as to be independent."

"What do you mean by that ?" said Marco.

"Why, I will put all that we shall both want in my little carpet-bag, and then we can go where we please, with our bag in our hands. A trunk is a great incumbrance on an excursion in search of the picturesque."

So Forester put some newspapers and a map into his carpet-bag, and then began to roll up some articles of dress into a small roll, which he was going to put into the carpet-bag too. Be held this roll in his hand a moment, hesitating, before he put it into the carpet-bag. "It will get sadly tumbled," said he, "knocking about in the cars and in the boats; I wish I had some way of protecting it."

"A trunk would be the best for it," said Marco.

Forester did not answer. He seemed to be musing.

"Never mind if it does get tumbled," said Marco.

"If I could find a tinman," said Forester, "I could get him to make a case for me in five minutes. Come with me, Marco," he continued, "and I will show you what I will do."

So Forester went down to the office of the hotel, and asked the clerk if he could direct him to a tinman's. The clerk went to the door, and told him to go in a certain direction, and into a certain street, and he would find a hardware store; and he said there was a tinman's in the rear of the store.

Forester and Marco walked along to the store. The store-keeper directed them out through a back door which led down some steps into a little yard, where the tinman's shop was situated.

When they entered, they found the tinman at his bench, hammering some tin with a small mallet. A little at one side of the place where he was sitting, was an enormous pair of shears, fixed in an upright position on the work-bench, all ready to cut. The jaws were short, but very heavy. They were what the tisman used in cutting his tin.

Forester told the man that he wanted him to do a little job.

"It must be a very little one, indeed," said the tinman, "for I am very busy. The other man that works with me is sick."

"Well," said Forester, "I will make it a very little one. I want you to cut me out two pieces of tin, about ten inches long and three wide, and then bend them up into half cylinders, so that when I put them together they will make a hollow tube. Then I should have liked to have some pieces soldered into the ends, but that is of no great consequence, if you can not do it conveniently."

"I will cut the piece out for you," said the tinman, "but I have not time now to solder in the ends."

So the man cut out the tins, and then, in order to bend them into a circular shape, he took a long, wooden roller, and rested one end on the bench and the other end upon the stool which he was sitting upon. Then he bent the tins over upon this roller, and hammered them with his mallet, so as to make them fit the roller in every part.

Forester found that he was taking more pains than was requisite, since it was not necessary for his purpose that the tins should be very true in their form, and besides, he knew that the man was in haste; so he said, "That will do, sir; it is not necessary to be very particular about it."

"Why, there is a maxim," said the tinman "that what is worth doing at all, is worth doing well."

"That is a very good maxim, I have no doubt," said Forester; "but the farmers in Vermont have another one, that it is not worth while to plane the under side of a barn floor."

The tinman laughed.

"As I suppose the true philosophy is," said Forester, "to go in the right medium between these two maxims."

By this time the tins were ready. Forester paid for them, and he and Marco returned to the hotel. Forester placed them one upon each side of the small parcel containing his linen, where they served as guards to protect the contents of the parcel from shocks and concussions. Marco, following Forester's guidance, found himself, not long after this, seated in a car, which was trundling him out of Albany.

They came very soon to a long ascent, which led up to higher land than that on which Albany was situated. For the land which lies in a direct line between Albany and Schenectady 18 elevated, though it is nearly level when you once get up, away from the river. The land is sandy too; so that it would have been easy to have made the excavation for a canal in a straight line, but it would have been difficult to have got a supply of water to keep it full. Besides, it would have been necessary to have had a great many locks in order to ascend from Albany to the table-land above, and then as many more to descend again to the Mohawk, at Schenectady. On account of these difficulties they did not attempt to carry the canal across this plain, but took it round, through the valley of the Mohawk, from Schenectady, thus bringing it down to Albany from the north. All this will be made very clear by looking upon the map.

The railroad, however, they made straight, and the consequence was, that it was necessary to have the cars drawn up a long ascent near Albany, in order to get them upon the high, level land above. Then at Schenectady there was another long descent, by which the cars were let down into the valley of the Mohawk. All this is, however, changed now, another route having been found for the railroad, which avoids these inclined planes.

Beyond Schenectady the railroad follows the valley of the Mohawk along to Utica, with the canal. So that for ninety miles there is a canal, a railroad, a river, and a common highway, running side by side, in the same narrow valley. It was up this valley that Forester and Marco were going to travel in one of the packet-boats of the canal, as soon as they reached Schenectady.

The cars were drawn up the long, inclined plane, -- so long that it seemed to Marco almost half a mile from the bottom to the top, -- by an engine which was stationed at the summit. There was a long cable, which reached from the top to the bottom of the hill. To keep the cable from dragging on the ground, they had a line of wheels in the middle of the track, between the rails. The cable passed along over the tops of the wheels. There was a groove made in the circumference of the wheels, to keep the cable from slipping off upon one side. Such wheels are called pulleys. When the cars reached the top of the inclined plane, there was a locomotive engine, that is, an engine which moved along the road, ready to be attached to it; and the locomotive soon carried the train across the elevated plain, and brought it to the brink of the hill, which descended into the valley of the Mohawk, at Schenectady. Here there was another inclined plane, and the train was let down slowly, by a stationary engine and a long cable, just as it had been drawn up at Albany. The locomotive was left at the top of the hill. At the foot of the hill they fastened horses to each one of the cars of the train, and drew them separately into Schenectady. Inclined planes are a source of great inconvenience upon a railroad. They make a great many changes and delays necessary. Still, there are some places where they can not well be avoided, though in this case, as has already been said, a new and more level route has been found, by which the ascent and descent that Marco and Forester passed over are now saved.

As Forester and Marco were sitting upon their seats in the car, just before they reached the inclined plane, the conductor came climbing along the side and looking in at the window to take their tickets. These cars were not made as cars are generally made now, with a door at each end, and an aisle up and down through the middle; but they were divided by partitions into three parts, and there was a door in each side. The conductor, however, did not come in at the door. He only looked in at the window, and when he had got the tickets, he climbed along to the next car.

"I should think he would fall off," said Marco.

"He takes care, I suppose," said Forester; "but I wish I had asked him something about the packet-boats at Schenectady."

"Why, we can find out well enough when get there," said Marco.

"Yes," said Forester, "but I expect there will be a great competition for passages. The runners will be after us, telling us all sorts of stories, and I should like to hear something about it beforehand."

"The runners ?" repeated Marco.

"Yes," said Forester; "the railroad people want travelers to go on the railroad, and the owners of the boats want them to go on the canal. So they each send out men to find the travelers as soon as they come into town, and try to persuade them to go by their conveyance. These men are called runners."

"Do you suppose they will be after us ?" said Marco.

"Yes," replied Forester, "very probably they will. The boats and cars both go at the same time, I believe, and both companies wish to get all the passengers."

"It will do no good for the railroad men to attempt to persuade us," said Marco; "for we shall go in the packet at any rate."

Forester was right in his expectation of being accosted by the runners on his arrival at Schenectady; for, as the car which they were seated in, was going into the depot, just before the horse had stopped, a man jumped upon the side of it, and looking in at the window, said, in an eager voice, to Forester,

"Going west, sir ?"

"Yes," said Forester.

"Will you take the packet, sir, carry you to Utica for twelve shillings."

At this instant another man applied at the window, just as Forester was taking up his carpet-bag and umbrella.

"Take the cars for Utica, sir?" said he. "Run through in six hours."

"You can have a good night's rest aboard the packet," said the packet runner.

"We will carry you for twelve shillings, sir," said the railroad runner, in a low tone, as Forester stepped out.

"Thank you," said Forester, "but I have some business along on the canal, and I believe I must take the packet."

"Well, sir, walk right along," said the packet man. "Have you any baggage ?"

"Only this," said Forester.

The man took Forester's bag and began to push his way through the crowd of persons that were coming and going in the depot, and Forester and Marco followed him without any more words. In fact, the noise and confusion of the bystanders, and the loud hissing of an engine, which was standing there, prevented conversation.

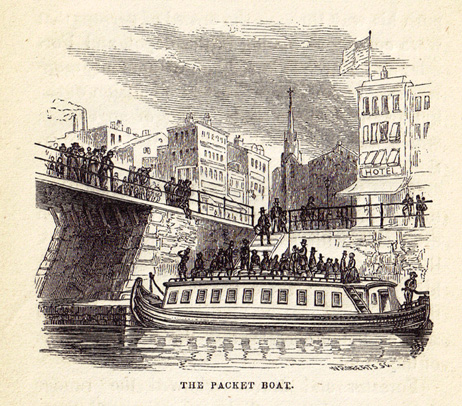

Their guide passed out of the depot, and then turned into a busy street, built up closely on each side with stores, shops, and taverns. A short distance before them they saw a high bridge. It was where the canal passed under the street. There was a flight of steps at each side of the bridge, leading down to the banks of the canal.

Forester and Marco followed the runner down one of those flight of stairs, and there they found a packet-boat ready to receive its passengers. The canal was very broad at this place. A canal is usually made broad where it passes through a town. Along the sides of it were walls of stone, and these walls were continued up, under the bridge, high enough to form abutments for the bridge to rest upon. The packet-boat was fastened by a rope to an iron hook in the lower part of the abutment of the bridge.

The boat was long and narrow, with a row of windows on each side. There were Venetian blinds, painted red, before these windows, and the boat itself was painted white. This gave it a very gay appearance. Marco said that it was a much handsomer boat than he had expected to find. The top of the boat, which formed a sort of deck, was nearly flat, being only curved a little from the center toward each side, so that the rain might run off. There was a very small iron railing, not more than six inches high, along the edges of it. This deck was four or five feet above the water. At the bows, and also at the stern of the boat, there was a lower deck, with steps to go down to it; and from the lower deck in the stern, there were other steps leading into the cabin. There was a row of trunks and carpetbags commenced on the deck, beginning near the bows; and men were carrying on more trunks, which they placed regularly in continuation of this row. The runner stepped from the stone wall by the side of the canal, upon the top of the boat, and Forester and Marco followed him. The man put Forester's carpetbag down with the rest of the baggage, and then he took the umbrella from Forester's hand, saying, that he would put that in the cabin.

http://www.eriecanal.org/texts/Abbott/chap02.html