FORESTER and Marco followed the runner down into the cabin. They found that it was a long and narrow room, which occupied almost the whole of the interior of the boat. It looked like a pleasant little parlor, only its shape was very long and narrow. There were seats on the sides, under the windows, covered with red cushions. They extended the whole length of the cabin. There were one or two tables in the middle, with some books and maps upon them. The cabin was divided into two parts by a projection from each of the two sides, which projections, how ever, were so narrow that they left a very wide opening between them, almost as wide as the whole breadth of the cabin. There was a large crimson curtain hanging over this opening, so that when the curtain was let down, it would divide the cabin into two distinct parts. When Forester and Marco came in, however, the curtain was up; the two halves being drawn out to the two sides, and supported there by a large brass curtain knob. Over this curtain there were painted in gilded letters the words, LADIES SALOON.

Marco understood from this arrangement that that part of the cabin which was beyond the curtain, was intended particularly for the ladies, and that it could at any time be separated from the other part by dropping the curtain. In the middle of the ladies' cabin was a table, with books and a bouquet of flowers upon it. There were several ladies sitting upon the cushioned seats at the sides of the saloon.

On the table in the gentlemen's part of the cabin, was a writing-desk, with a large sheet of paper upon it. This was the way-bill, on which the names of the passengers were to be entered. The clerk, who was in the cabin when Forester and Marco came in, took a pencil up from the till of the desk, and said to Forester,

"What name, sir ?"

"Forester; and this lad's name is Baron," said Forester.

So the clerk wrote Mr. Forester upon the list. Forester observed that there were only two names there before. Under Mr. Forester, the clerk wrote the name Baron.

"What time do you go ?" said Forester.

"At nine o'clock," said the clerk.

Forester looked about the boat a few minutes more, and then went up on deck again, and stepped off the boat upon the bank.

"It will be an hour," said Forester, "before we shall go. So we will ramble about the town a little, and see what is to be seen."

They ascended the long flight of stairs again, which led up to the bridge. When they reached the top, Forester proposed that they should go across the bridge, and look at the canal on the other side.

They went accordingly to the other side, and looked down upon the broad and smooth surface of the water which was spread out below them. The view of the canal extended for some distance, until it was lost by the canal's curving around to the right, where the prospect was intercepted by buildings. On the left side was a sort of street, with the canal on one side and a row of small shops and warehouses on the other. There were a great many men and large boys standing idle in this street, and lounging around the posts which were set near the edge of the canal. There were stalls near, with nuts and oranges for sale; and children playing with each other, so near the brink of the water, that Forester thought they must be in danger of falling in. On the other side of the canal there was a path, called the towpath. It was for the horses to go in when drawing the boats along the canal.

While they stood thus upon the bridge, looking down upon the water, suddenly Marco perceived two horses coming into view along the curve of the tow-path, at a little distance below. They were harnessed one before the other, and were drawing a long rope. A moment afterward, the bow of a canal-boat, which the horses were towing, appeared, and then the whole length of the boat glided into view. It was not by any means so handsome a boat as the packet which they had taken passage in, and the deck was covered with long rows of barrels.

"There comes a load of flour, I suppose," said Forester, "from the west."

"Is that flour ?" asked Marco.

"I presume so," said Forester. "I know that a very large part of the business of this canal is transporting flour from the west. In fact, that was one of the chief things it was made for. There is a large tract of land in the western part of this state, and all around Lake Erie, and the other lakes, which produces immense quantities of wheat, and it was thought that, if they made this canal, the flour might be brought down very easily."

"Did the farmers make the canal ?"

"No," said Forester; "the State of New York made it."

"Why did they make it ?" said Marco; "it was not their flour that was to be brought down."

"No, but then the government knew that it would be of great advantage to all the farmers of the state to have the means of bringing their produce to market; and, besides, they knew they could manage it so that the state should get paid again for making the canal."

"How ?" said Marco.

"By making every one pay toll that comes through with a boat. This man, with his load of flour has had to stop somewhere and pay toll for every barrel. So, if a man owns a packetboat, he has to pay toll for every passenger."

" I should think the passengers ought to pay toll themselves," said Marco.

"They do, in fact, for the packet-man charges them enough to pay their toll, and also to pay him for carrying them in his boat. But it is more convenient to have the packet-master pay once for all, than it is for every man to stop and pay his own toll."

"Why, every man has to pay to the packetman," said Marco.

"Yes," said Forester; "but then he does it at the same time that he pays his own fare, settling for both in one payment, so that it is no additional trouble. So all the masters of the boats have to pay tolls, I suppose, for all the merchandise and all the passengers they carry; and all these tolls are collected together, and paid to the government of the state, and they make a very large sum every year. But it is not so with the railroad."

"Why not ?" said Marco.

"Why, the railroad was built by a company of individuals, who put their money together, and they built or bought the cars and engine too. So that the same parties which own the railroad own the cars and engine; and they carry all the passengers and all the freight themselves. They do not allow any body else to run on their road. But the State of New York does not own the canal-boats. It only owns the canal itself, and it allows any body to run boats on the canal, if they will only pay the tolls. There is no danger in having ever so many boats go to and fro, because they can pass by one another very easily, but different trains of cars, owned by different parties, would be always coming into collision."

"I don't see how the boats can pass by each other," said Marco. "I should think that the horses and the ropes would get entangled."

"No," said Forester; "they have no difficulty; you will see how they manage it, when we go in our packet."

Long before this time, the line boat, which they had seen coming, had passed under the bridge, and gone on out of sight. So Forester and Marco turned away from the bridge, and began to walk about the street.

Presently they came to a hotel near the railroad depot, and as they were rather tired of walking, they went in and sat down. Marco began to read a newspaper. Forester saw a desk in one corner of the room where the stagebooks were kept, and he told Marco that he was going there to write a letter.

Forester always carried two or three sheets of white paper folded in his pocketbook, and also a pen. He had, besides, a little pocket inkstand and wafer-box, so that he could write his letters at any time and place, when he had a few minutes of leisure. He accordingly went to the desk and remained there nearly half an hour, writing, and then he folded up his paper and came back and told Marco it was time for them to go aboard of the packet.

When they came in sight of the bridge, they found a large number of men and boys standing upon it, looking over the railing, or sitting upon the upper steps of the stairs.

"What can be the matter there ?" said Forester. "I do not know," said Marco.

They went on to the place and looked down upon the canal. The packet was there, in the same position in which they had left it. There were, however, a great many more persons on and around it, and the row of trunks and carpet-bags had now extended almost the whole length of the boat, from stem to stern. Forester and Marco supposed that some difficulty or trouble must have occurred to draw so great a crowd, but on looking down upon the scene, from the bridge, they could not perceive any indications that any accident had happened, and besides, now they were near, they perceived that the crowd were calm and quiet, looking as if they were waiting for something yet to come, rather than interested in any thing which was then taking place.

"It can not be," said Forester, "that all these people have come just to see the packet sail ! I should have supposed they would have seen a packet sail often enough at Schenectady, by this time."

"I do not know," said Marco, shaking his head, "I do not know any thing about it."

They passed through the crowd and went down the steps, and then got upon the boat; though the space not occupied by trunks was so fully occupied by men, that it was difficult for them to move about. At length Forester found a good place to sit down. The seat was a trunk, and there was a roll of carpeting upon the other baggage near, which was very good to lean upon. Here Marco and Forester established themselves, and their attention was soon absorbed in the novelty and interest of the busy scene around them.

They had not been many minutes in this position, when they saw several musical instruments appear at the head of the flight of stairs, which descended from the bridge. There was a bugle, a trumpet, a clarinet, and drums.

"Ah!" said Forester, "here comes a band of music. This explains the mystery. The people have come to hear the music."

The musicians came down the stairs, and stepped over to the boat, and took their stations at the bows. A moment afterward, the band struck suddenly into a fine martial air, which made Marco jump up from his seat, so as to get a better position to see. He stood upon a box, gazing alternately upon the trumpeter and the drummer with great delight.

Forester might have been expected to have participated, at least in some degree, in this pleasure, for he liked martial music very much. To Marco's great surprise, however, he suddenly rose, and taking Marco by the hand, said, " Marco, come with me."

Forester passed rapidly along, wherever he could find an opening through the passengers who thronged the deck, and clambering over the baggage, jumped off the boat to the shore, and began to work his way as fast as he could, wherever he could find a passage through the crowd, toward the stairs, and then up to the bridge. Marco had no opportunity to ask him where he was going. As soon as he reached the street, he said,

"I have left my little inkstand at the tavern. I shall just have time to run and get it. Come along as fast as you can."

"Well," said Marco, "only if they go off before we get back, we shall lose our baggage."

"I do not think they will go off," said Forester. " It is five minutes of nine yet. Besides, I presume they will play a little while before they go. At any rate, I must have my inkstand."

They hastened to the. tavern. Marco remained at the door while Forester went in. He found his little inkstand on the desk where he had left it. The cover was by the side of it. He seized his lost property, and hastened back to the door, screwing on the cover as he went. "Have you got it ?" said Marco.

"Yes," said Forester, "and now we will go back as fast as we can."

"And if they have gone you will lose your baggage."

"No," said Forester, "for we can go by the railroad, and so get to Utica before the packet, and wait there till it comes, and thus get our baggage. But I think we shall be in time."

Forester was mistaken. As they looked toward the bridge they saw the crowd running across, from the lower side, where they had been standing, to the upper side, which indicated very certainly that the packet was passing under the bridge. This was confirmed by the sound of the music, which they could now distinctly perceive was in motion, as the boat, bearing the band upon the deck, was gliding along upon the water.

Now it happened that just as Forester and Marco were running thus toward the bridge, they perceived another young man before them, having a paper of some sort in his hand, who appeared to be also making his way as fast as possible toward the boat. The people on the bridge, seeing at once that there were passengers left behind, began immediately to shout to the packet.

"Ho !" said one.

"Hold up !" said another.

"Ho-a--H-e-y !" cried another.

If it had been daylight those on board the packet would probably at once have perceived the truth of the case, and the captain would have ordered the boy, who was driving the horses on the tow-path, to have stopped. But it was now nine o'clock. There was a moon rising, it is true, which furnished light enough to enable those who were on the bridge to see Forester and the others running, but they could not see them from the packet. And then the loud notes of the music in a great measure drowned the sound of the voices calling upon the packet to stop. The boy who was driving, looked around and slackened his pace, but he had been going very swiftly before, and the boat glided along rapidly with the momentum it had already acquired. Some of the musicians, hearing a hubbub, stopped playing; others went on. In fact, the boat and all connected with it, assumed an expression of the utmost uncertainty and indecision.

"We will run on and overtake them," said the young man with the paper in his hand. Forester supposed that he belonged to the boat, and he and Marco followed him.

They ran down the bank of the canal on the upper side of the bridge, where they had seen the stalls of nuts and oranges. The canal was here very wide, being expanded into a sort of basin, and as the tow-path was on the opposite bank, the packet was at a considerable distance from them. If they had crossed the bridge before they descended to the bank of the canal, it would have been better, as this would have brought them upon the tow-path, where they would have been nearer the packet; and it would have been easy for the helmsman to have steered up near to the bank, so that they might have jumped on. But they had no time to think of this, and thus it happened that they found themselves running along the bank on the wrong side of the canal.

The packet went slower and slower, and the music ceased. Forester and his party found that they were getting before it.

"We will run on here to the next bridge," said the young man, "and then we can get aboard."

Forester had thus far supposed that this young man was connected with the boat in some way, and was only endeavoring to stop it, in order that he and Marco might get on board. When he found, however, that he was putting himself to a great deal of trouble, he said,

"Oh, it's of no great consequence, sir; we don't care particularly about getting on board."

"But I want to get on board myself," said the young man.

"Do you belong to the boat ?" asked Forester.

"No," said the young man; "but I want to go on her. We will run along to this next bridge, and then we can jump down on the boat when she passes under."

"I don't know," said Forester; "I expect you are more used to jumping off from a bridge upon a canal-boat, than we are."

"Oh, you can do it," said the young man, "only you must be quick; she'll go under like a shot."

Forester had no idea of exposing either himself or Marco to any risk. Still they pressed on, half running half walking, for a short distance farther, when they reached at length a long wooden bridge, which here crossed the canal. It was old, and high above the water; and it shook fearfully as they went over it. They had, however, outstripped the packet, for when they got upon the middle of the bridge, they saw it quite behind them, but coming along slowly up the canal.

There was also another boat just then coming down the canal, and the horses of the two boats passed each other under the bridge, just as Forester and Marco were going over above; and when they got down upon the tow-path, on the other side, the two boats were just shooting under the bridge, one in one direction and the other in the other. Marco thought that they would certainly come into collision; and in fact the tow-lines seemed to him already all entangled together.

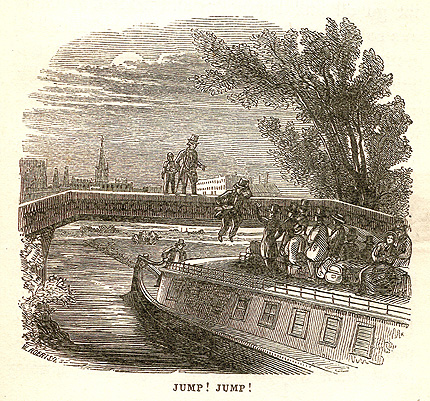

However, the boats did not interfere; the horses and the tow-lines cleared each other in a moment, and the packet came gliding along, not far from the bridge where Forester and Marco were standing. The young man jumped on board, and the people who were standing upon the lower deck at the stern, held out their hands to Forester, and said, "Jump ! jump !"

They spoke eagerly, for the boat was then receding again, and they knew that in a moment it would be too late. Forester saw this too; but he did not attempt to jump. He shook his head, and said,

"Not I. I have no idea of getting into the canal."

In fact, Forester felt very easy about his passage now, for he knew very well that after showing so much eagerness to get passengers, the man who had charge of the packet would not go off and leave him and Marco, when it was so easy to slacken their speed and let them get in. If a man arrives at a landing just too late for the steamboat, his case is generally hopeless; for a steamboat is so large and unwieldy, and it moves, when it is once put in motion, with so great a momentum, that it is seldom worth while to stop for a single passenger. The case is very different with a packet on the canal.

As Forester expected, the helmsman put his helm off to the farther side of the boat, and this caused the bows to turn in toward the shore. It came so near that Forester and Marco stepped on board without any difficulty. They made their way as well as they could, among the men who were still standing upon the deck, to their former position by the roll of carpeting, where they took their seats again. The boy whipped up his horses, the musicians commenced playing the Grand March in Abaellino, the boat began to glide swiftly along, washing the banks with the swell, which followed in her stern, -- and behold, Marco and Forester fairly embarked on the canal.

http://www.eriecanal.org/texts/Abbott/chap03.html